Dec

30

Jobs: Rebirth, from Bill Rafter

December 30, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Monitoring the U.S. economy through job growth has been unusually difficult in recent months. Under normal circumstances, the labor data would offer a clean read on economic momentum. Instead, a politically driven government shutdown temporarily removed millions of workers from payrolls, distorting every major employment indicator. The strategy failed to achieve its political aims, but it forced millions of Americans to forgo paychecks until the shutdown ended—leaving analysts with a statistical mess to untangle.

The central question now is straightforward but critical: How much of the current job growth reflects genuine economic expansion, and how much is simply the reinstatement of furloughed workers—or seasonal part-time hiring for the holidays?

The next Non-Farm Payroll Report arrives Friday, January 2, 2026, and for the first time in months we may get a clearer signal. Our estimate points to a substantial increase in jobs, driven entirely by the behavior of Payroll Tax Receipts, which have long been our most reliable real-time indicator of labor market strength.

After a period of negative growth, Payroll Tax Receipts have turned sharply upward. As shown in the accompanying chart, the leading indicator (red line) has lagged the actual receipts (blue line) during the shutdown distortions, but is now crossing above and beginning to lead the series higher. This is not a temporary blip. It marks the beginning of a multi-year positive trend—one we forecasted months ago and which is now unfolding exactly as expected.

Our estimate for the January 2nd NFP Report: +162,000 jobs

If this projection holds, it will confirm that the underlying economy has regained its footing and that the Payroll Tax Receipt signal is once again pointing the way forward.

Sorry — 4.3% GDP Growth Isn’t Real

Several major outlets (Bloomberg, CNBC, Axios) recently reported that the U.S. economy grew at an annualized 4.3% pace in Q3 2025. The number comes from a delayed BEA release (12/23) that extrapolated partial quarterly data into an annual rate. But that headline figure simply doesn’t match real-time economic activity.

Payroll Tax Receipts Tell the Truth

Our most reliable indicator of economic momentum has always been Payroll Tax Receipts. They reflect actual wages and actual jobs — not model-based projections.

Here’s what the tax data shows:

During Q3 2025, Payroll Tax Receipt growth was never positive.

Annualized growth for the quarter averaged 1.42%, and that’s looking back over a full year.

Current annualized growth through Christmas 2025 is under 0.5%.

Those numbers are nowhere near 4.3%.

Why the BEA Estimate Misleads

The BEA’s figure is:

Annualized — multiplying a partial quarter by four

Distorted by the government shutdown, which delayed data collection

Contradicted by real-time tax flows that never showed a surge

Even the BEA notes this is an initial estimate, replacing two missed releases. It is unusually fragile and backward-looking.

Interpretations Will Vary — But the Data Doesn’t

Some may speculate that an unexpectedly high GDP print could influence monetary policy by suggesting renewed inflation pressure. Whether or not one believes that, the conclusion is straightforward:

The 4.3% GDP claim cannot be supported by real economic data.

Payroll Tax Receipts — the cleanest, least-manipulable indicator we have — show growth well under 1%, not 4%.

Larry Williams adds:

One of the best predictors of jobs is the stock market, which is also forecasting more people back to work.

Nov

22

Getting back to normal with Jobs data, from Bill Rafter

November 22, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Chart: Full-time vs, Part-time Employment Growth Rates

Oct

22

Government shutdown question, from Cagdas Tuna

October 22, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Are the furloughed government employees going to be counted as unemployed? I believe they will be which will be considered as a huge green light for 50bps rate cut in the December FOMC. This shutdown is the perfect storm for Trump’s “Fire Powell and get rates to 0%” scenario.

Bill Rafter responds:

The requirements for being “Unemployed” are that (a) the person is not working , and (b) that person is “looking for work”. I believe the latter qualification would disqualify those furloughed from being considered as unemployed. Not only the shutdown [will delay BLS releases], but the recently nominated BLS head, E.J. Antoni has withdrawn his name from nomination. So BLS is headless.

Alex Castaldo comments:

That is good news for all statisticians, I am sure he is a wonderful guy but he had a reputation for mistakes in calculations.

Aug

12

A deeper look at employment, from Bill Rafter

August 12, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Positive Economic News: Full-Time vs Part-Time Employment Growth

Over the past year the pace of full-time hiring has outstripped that of part-time positions. Both categories are growing, but full-time roles have seen a steeper upward trajectory once we normalize for scale. This signals that employers are increasingly confident in committing to long-term payrolls.

To compare growth on equal footing, we fit simple linear regressions to each series (full-time employment level and part-time employment level) over the same interval. We used monthly seasonally adjusted data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. For each series, we calculated the slope (employees per month) of the best-fit line. Those slopes became our normalized growth measures, avoiding raw-level distortions.

Empirical Results

Full-Time Employees +2150.00

Part-Time Employees +950.44

The full-time slope of +215 K/month means that on average, net full-time headcount has risen by 215,000 each month. Part-time roles have climbed as well, but at roughly 44 percent of the full-time rate.

A faster acceleration in full-time positions suggests businesses are shifting from flexible or contingent staffing toward more stable, long-term commitments. This pattern often accompanies stronger consumer confidence and investment plans.

Hiring more full-time workers typically entails higher benefits, training, and overhead, so firms generally only follow through when they foresee sustained demand. The fact that part-time growth remains positive underscores broad underlying strength in the labor market.

Consumer spending power will likely rise as more workers move into full-time, benefit-eligible roles. Wage growth pressures may pick up if the pool of available long-term hires tightens further.

Capital expenditure plans may accelerate as firms brace for continued demand and aim to boost productivity.

Jul

21

CPI Data Quality Declining

July 21, 2025 | Leave a Comment

CPI Data Quality Declining

June 20, 2025

Torsten Sløk

Apollo Chief Economist

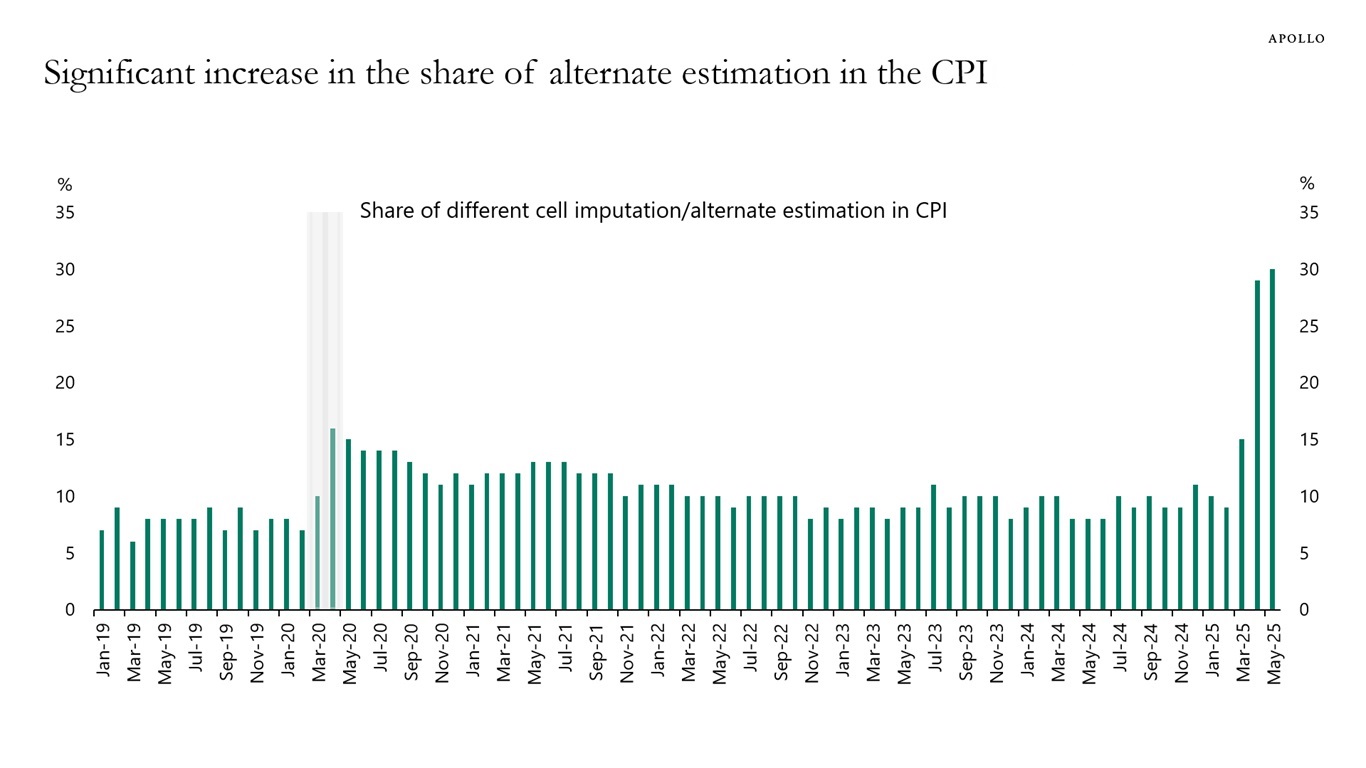

To calculate CPI inflation, BLS teams collect about 90,000 price quotes every month covering 200 different item categories, and there are several hundred field collectors active across 75 urban areas.

When data is not available, BLS staff typically develop estimates for approximately 10% of the cells in the CPI calculation. However, in May, the share of data in the CPI that is estimated increased to 30%, see chart below.

In other words, almost a third of the prices going into the CPI at the moment are guesses based on other data collections in the CPI.

Bill Rafter writes:

Would anyone in the data business be surprised by this? I’m not.

Peter Ringel wonders:

Doge related?

Big Al offers:

US Labor Department reducing CPI collection sample amid hiring freeze

By Reuters

June 4, 2025

The U.S. Labor Department's economic statistics arm said on Wednesday it was reducing the Consumer Price Index collection sample in areas across the country due to resource constraints, but the move should have "minimal impact" on the overall CPI data.

Jul

18

C & I loans, Large v. Small banks, from Bill Rafter

July 18, 2025 | Leave a Comment

In the July 14 Wall Street Journal, an article argued that smaller banks—by virtue of their loan portfolios—are better positioned than larger banks to gauge the nation’s economic health. Intrigued, I tested that claim using Federal Reserve weekly data on Commercial & Industrial loans for both large and small banks going back to 1984.

As expected, small-bank lending proved more volatile, but it was consistently less “correct” than large-bank lending. Whether measured by simple rates of change or by shifts in their 12-month trends, large banks outperformed small banks in accuracy. This analysis does not include loan-performance metrics (delinquency or charge-off rates broken out by bank size), which — unsurprisingly — tend to peak during or immediately after recessions.

Jun

9

Analyzing Employment Trends: Full-Time vs. Part-Time Work, from Bill Rafter

June 9, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Within the Non-Farm Payrolls (NFP) Report, two key employment categories—full-time employment and part-time employment for economic reasons—offer valuable insight into the state of the labor market. By analyzing their respective growth trends and comparing their slopes, we can better understand shifts in employer confidence and economic stability. Historically, economic downturns have occurred when part-time job growth surpasses full-time employment growth, reflecting caution among employers hesitant to commit to permanent positions. Conversely, economic recovery typically begins when full-time employment accelerates faster than part-time hiring, signaling renewed confidence in long-term business prospects.

Full-time employment has been growing steadily for the past six months and increasing consistently for 11 consecutive months. Part-time job growth, though still exceeding full-time growth, has declined over the last two months. This shift suggests a potential turning point in labor market trends. While employers have not fully transitioned to long-term hiring, the upward momentum in full-time job growth indicates gradual economic stabilization.

If this pattern continues, we may see full-time employment overtaking part-time growth, solidifying economic recovery. Monitoring sector-specific hiring trends—such as whether certain industries are driving full-time job gains—can provide additional insight into the strength of this shift. Wage growth and labor force participation are also critical factors to watch.

Mar

8

Jobs, from Bill Rafter

March 8, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Despite what talking heads may say about Jobs and the current Non-Farm Payrolls Report, there are two items that suggest Recessionary times. The current (daily) Payroll Tax Receipts growth, and the dichotomy between Full-time and Part-time workers (monthly). Click on the charts to open them for full view.

Feb

11

Full vs part-Time employment growth rates, from Bill Rafter

February 11, 2025 | 1 Comment

Steve Ellison wonders:

Will NBER ever acknowledge there was a recession? Or maybe as in 2001, they will retrospectively announce a recession after the recession has already ended. The job market for white collar job seekers was horrendous in 2023 and 2024. But GDP never went negative. "Learn to code" is out; "Learn to weld" is in.

Bill Rafter responds:

Yes, there was Recession. If bureaucrats in power refuse to admit the obvious, or use obtuse metrics to define economic activity, then the Intelligent Man has to find another way to define or measure that activity. The chart below, of Payroll Tax Receipts Growth, matches the negative period you described.

Feb

3

Inflation and it’s Causes, from Asindu Drileba

February 3, 2025 | Leave a Comment

What causes inflation? Suppose we define inflation simply as the rise in prices of commodities, stocks, real estate etc. What causes it?

1) A generic explanation people offer (acolytes of Milton Friedman & Margaret Thatcher for example) is to blame monetary policy. Simplified as, inflation is caused by "too much money chasing too few goods."

Many people blamed President Trump's COVID stimulus packages for the rise of prices during that period. It seems specs in this list agree upon this when it comes to stock prices, i.e., lower interest rates (higher money supply) -> Higher stock prices (inflated stock prices).

2) An alternative explanation is that higher prices are caused by supply chain issues.

So they would claim that higher commodity prices were so because it was extremely difficult to move them around during lockdowns, let alone processing them in factories. A member also described that egg prices may be going up because of disease (a chink in the supply chain) not necessarily monetary policy. I am thinking that supply chain issues are more important to look at, than monetary policy.

Larry Williams predicts:

Inflation is very, very cyclical so maybe the real cause resides in the human condition and emotions. It will continue to edge lower until 2026.

Yelena Sennett asks:

Larry, can you please elaborate? Do you mean that when people are optimistic about the future, they spend more, demand increases, and prices go up? And then the reverse happens when they’re pessimistic?

Larry Williams responds:

Just that it is very cyclical— as to what drives the cycles I am not wise enough to know…though I suspect…some emotional pattern dwells in the heart and souls of as all that creates human activity—along the lines of Edgar Lawrence Smiths work.

Dec

9

This is what recovery looks like, from Bill Rafter

December 9, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Payroll Tax Receipts growth:

More charts (click for full view):

Payroll Tax Receipts growth with a leading indicator

Employment: full-time vs part-time

Nov

30

Productivity and AI, from David Lillienfeld

November 30, 2024 | 1 Comment

When do we start seeing the effects of AI show up in national economic data? If you had invested $5K in a laptop and a word processing program, you could replace a secretary at multiples of the cost. When the web came in, there was Amazon squeezing out the costs of the middlemen.

But I don't see the savings for AI. I see lots of talk, some free programs, but in terms of real productivity, not so much. I'm also told that it's early days and I'm asking for too much in posing such a question, but I think we're now getting far enough into AI that it's not an unreasonable matter to bring up.

One thing that's clear is that AI isn't going to generate employment the way the last tech push did. But if it's going to really change the world as its advocates suggest that it will, those productivity gains should be apparent by now.

M. Humbert writes:

However AI productivity gains are measured, it’ll have to account for the productivity loss due to its high energy consumption. For the Austrian economics fans here. I’ve found Copilot to be a helpful time saving tool, so others probably do as well, so time savings definitely are occurring from AI use today.

Laurence Glazier responds:

Using it all the time, huge experiential benefit. Chatting to GPT every morning while reading Thoreau. Instant context. The other big breakthrough is spatial computing. All in the service of art.

Asindu Drileba comments:

From my experience, co-pilot and other LLMs, have not solved anything that could not already be done via ordinary Googling. Looking up solutions to code issues on stack overflow is no different from LLMs. And stack overflow is still better for some tasks (fringe computer languages like APL for example). LLMs are impressive, but are mostly just gimmicks. The only thing it has actually saved me time on is generating copyrighter material and filler text.

Jeffrey Hirsch adds:

Just had that discussion today about ordinary google still being even better than LLM Ais in finding info. Had some fun with AI editing and embellishing copy.

Asindu Drileba adds:

I suspect that the bad SWE job market is due to high interest rates, no AI. The SWE job market is enriched mostly by VC money. And VC money dried up when LPs withdraw to earn risk free money in treasuries instead of betting on start-ups whose success is on probability. I expect it to recover if interest rates come down to previous levels.

I think the LLM narrative was just something that tech executives parroted to show they had an LLM strategy. It's, Like how in 2018/2017 every executive had a "Blockchain" strategy. A lot of businesses assumed that LLMs would replace simple customer support jobs but they just saw their tickets pile up. Even the $2B valued, Peter Thiel financed, code assistant that would make you money on Up work as you sleep turned out to be a blatant scam.

Steve Ellison writes:

I don't have an answer for Dr. Lilienfeld's question about when AI effects will show up in productivity statistics. But I do hear anecdotally through my professional networks that AI projects are adding real value.

At the same time, Asindu is correct that the bad job market for techies, myself included, is more a consequence of rising interest rates–and I would add overhiring during the pandemic–than positions being replaced by AI. As Phyl Terry put it, "But this company [that announced layoffs] wants to go public so the better story is 'we are smart leaders using AI to become more efficient and profitable' vs 'we were idiots during the pandemic and have to lay off some people because we messed up.'"

Gyve Bones writes:

I find that the AI's ability to interpret my request and put together a coherent synthesis of several sources to be very helpful. Grok is nice because it provides a set of links to sources relevant to the prompt, and to related ??-posts and threads.

Laurence Glazier asks:

I usually have audio conversations with GPT rather than the older typed-in input/output. I just subscribed to X Premium to get access to Grok. Any good links for learning good usage? How nice Musk names it from the Heinlein novel.

Gyve Bones responds:

Check out the sample prompts Grok supplies on the [ / ] section in ??. The news analysis prompts for trending items is pretty cool.

Bill Rafter writes:

My business partner and I are in the process of marketing a new software application. Although we are rather literate, we have been running all of our marketing materials through Copilot, and we are amazed at the improvements Copilot makes to our text. It results not only in improved communication, but is a real time-saver. We even asked it to write a business plan, and it came back with a better one than our original.

Peter Penha offers:

I have not (yet) been on Grok but have found that the prompts do not differ very much across LLMs:

A Primer on Prompting Techniques, June 2024.

Prompt engineering is an increasingly important skill set needed to converse effectively with large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT. Prompts are instructions given to an LLM to enforce rules, automate processes, and ensure specific qualities (and quantities) of generated output. Prompts are also a form of programming that can customize the outputs and interactions with an LLM. This paper describes a catalog of prompt engineering techniques presented in pattern form that have been applied to solve common problems when conversing with LLMs. Prompt patterns are a knowledge transfer method analogous to software patterns since they provide reusable solutions to common problems faced in a particular context, i.e., output generation and interaction when working with LLMs. This paper provides the following contributions to research on prompt engineering that apply LLMs to automate software development tasks. First, it provides a framework for documenting patterns for structuring prompts to solve a range of problems so that they can be adapted to different domains. Second, it presents a catalog of patterns that have been applied successfully to improve the outputs of LLM conversations. Third, it explains how prompts can be built from multiple patterns and illustrates prompt patterns that benefit from combination with other prompt patterns.

This is earlier/shorter February 2023 paper - I am also a fan/follower of Prof. Jules White’s classes on Coursera why I flag the shorter/earlier paper as well.

Separate on the subject of AI - Eric Schmidt has a new book Genesis with Dr. Kissinger as a co-author (his last work before his passing) but Schmidt did a Prof G Pod Conversation released Nov 21st - in the podcast Schmidt goes over the threat from LLMs that are unleashed and noted that China in his view has open sourced an LLM equal to Llama 3 and that China instead of a being three years behind the USA on LLMs is a year behind. That China comment can be found here at 26:30.

Finally if anyone wants a great book I have read, on the history of the race to AGI going back to 2009: the Parmy Olsen book Supremacy on the histories of Sam Altman and Demis Hassabis is a wonderful read. Also breaks the world down between the AI accelerationists and the AI armaggedonists.

Big Al adds:

I do use Bard to learn or refresh my memory with R. For example, I am trying to use the "tidyverse" set of packages, and Bard is very useful when asked to write code for some task specifically using, say, tidyquant. The code almost never works first time cut & paste, but I can see how things are done differently and figure out what needs fixing. And I get answers to simpler problems faster than on Stack Exchange which is better for more complicated issues.

Laurence Glazier comments:

It's an inverted Turing test situation. The things that AI can't do help identify our humanity, our birthright.

Nov

14

Crypto and the money supply, from Bill Rafter

November 14, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Should the market cap of crypto currencies be included in money supply for macroeconomic purposes?

William Huggins replies:

I'd you cant use it to pay taxes it doesn't count (just another asset, like a stamp).

Kim Zussman asks:

Why not? They add because if you pay taxes with fiat you can buy merch with crypto.

William Huggins responds:

you can barter wine or chocolate for a ton of things online too but we don't count those either. if money is "anything taken as payment" then we have to get very serious about "degrees of moneyness" (hence m0,m1,etc). in that spectrum, its pretty clear that the only things on the list are legal tender so unless you live in the land of bukele, it doesn't count (also, whose money supply does crypto count as exactly?)

Peter Penha:

I will volunteer that there is no moneyness to crypto as it was determined a 100% haircut asset by the DTC.

I think this leaves Blackrock and other crypto ETF managers in the interesting position that they cannot include crypto ETFs in one of their asset allocation funds or a target date fund, etc - inclusion would pollute.

Crypto in the USA appears to be a walled garden - the only contagion I can see to the financial world would be to holders of Micro Strategy Convertible Debt.

Stefan Jovanovich writes:

The question you all are raising here has a history - how far can "the law" go to monetize promises to pay? Originally, the answer was not one step. The Constitution says that legal tender can only be Coin. Article I, Section 8.

The lawyers have been working around that limitation ever since. Their greatest difficulty has been getting around the literalist non-lawyer Presidents who keep following the actual instructions the People established by vote as "the law".

Success came with the Aldrich-Vreeland Act which authorized banks with Federal charters to form "currency associations". Those were given authority to issue emergency currency could be backed by securities other than U.S. bonds, including commercial paper, state and local bonds, and other miscellaneous securities.

Section 18 of the Act: "The Secretary of the Treasury may, in his discretion, extend from time to time the benefits of this Act to all qualified State banks and trust companies, which have joined the Federal reserve system, or which may contract to join within fifteen days after the passage of this Act: Provided, That such State banks and trust companies shall be subject to the same regulations and restrictions as are national banks under this Act: And provided further, That the circulating notes issued under this Act shall be lawful money and a legal tender in payment of all debts, public and private, within the United States."

Everything since 1908 has been a variation on that theme - "lawful money" can be whatever Congress says it is.

Bill Rafter comments:

I started this question because I am working on a slight variation of digitally quantifying inflation. With the loose definition of inflation being “too much money chasing too few goods”, then the “money” part should include all that can conceivably buy the “goods”. Since one can increasingly buy a whole lot of stuff with crypto, then crypto deserves inclusion. If one were to fast-forward to a time of massive currency instability (this is just a thought experiment), having included the cryptocurrency might have facilitated greater forecasting.

Stefan Jovanovich adds:

For me the paradox of Bitcoin is that it has been a spectacularly successful asset - like a share of Berkshire Hathaway stock bought in the days before Buffett even went public - but it has never been a money. If I had Bill's brain and cleverness, I would try to include in the calculations the sum of personal and corporate credit that the lenders cannot easily pull away from the table (the potential moneyness supply) and the amount of credit actually used; and then seek the correlations to the fluctuations in that spread. In the days before central banking, speculators watched the net supply of commercial paper as such an indicator.

Sep

9

Full-time vs. Part-time Employment, from Bill Rafter

September 9, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Bud Conrad comments:

The US BLS understates inflation, which causes the calculation for Real GDP growth to become overstated. Thus, we have a recession going on, but it is hidden by the BLS's low inflation rate. The rich are doing well as asset prices have risen; the rest have lost ground because the cost of everything has increased more than the labor rates.

Ditto on jobs and employment that suggests there are lots of new jobs every month, but then restates the number downward in succeeding months, which accumulated to 818 K jobs that are overcounted in the year ending March.

The supposed Fed's being "data dependent" is a cop-out from thinking "How to stabilize the dollar", meaning that they claim they will use these corrupt numbers for policy decisions.

Jul

20

Looking deeper into employment, from Bill Rafter

July 20, 2024 | Leave a Comment

First the chart. The two data sets are of different magnitude, so to compare them they must be normalized. The chart represents the slope of the data divided by the trend of that data. Both are determined by regression over 12 months. Each point on the chart is effectively the expected rate of change of the data as determined by the moving trendline. As such, the data is NOT lagged, and presents a truer picture than that of lagged data.

Interpretation. Periods of higher part-time employment tend to coincide with recessions. However, if the employment picture is recessionary, then how would one explain the growth in Payroll Tax Receipts, which I have shown separately? Well, it turns out that the growth from January to June in Part-time employment matches the growth in Payroll Tax Receipts. Thus, the economy is growing solely by the increase of part-timers.

Zubin Al Genubi writes:

Many young people I know do gigs, seasonally or part time. Recent employment numbers (with temp way up and full-time way down)support the theory.

Humbert H. adds:

I’ve seen a lot of information on part-time vs full-time. Often it’s accompanied by foreign-born vs native-born, where the dichotomy is similar, in favor of the foreign-born.

Jul

4

Bud Conrad is not sanguine:

We avoided an official recession despite negative 2% to 3% tax growth. The Treasury and the deficits were pumping money into the economy in 2023. It now looks like no problem in Tax receipts, but I just don't believe that things are clear sailing. Wars, Debts, Foreigners cashing in Treasuries from their trade surpluses (our Trade deficit), Stock market toppy concentration in the Tech winners. Incompetent politicians. I think things are worse than I think they are.

Steve Ellison keeps the wall of worry updated:

Updated! Now 53 years of convincing reasons why the stock market should go down, superimposed over the 48x increase in the S&P 500 during the same time period (logarithmic scale). 2023: Nearly everybody expected a recession. That reason is added, along with the S&P's 24% increase.

Mar

24

An alternate understanding of a market being at all time high (market reaching new prices it has never encountered) is this: "Everyone that has ever bought that stock or instrument is now in profit". What might be the psychological implications of this?

Kim Zussman comments:

It is possible (and probable) to buy, then sell after a decline and stay out only to see it reverse and go up further. This (timing) is one reason it is so much easier to do better with B/H than trading.

Big Al adds:

The other advantage to B&H is that the opportunity cost viz time/attention required is basically zero. I have looked at various index timing approaches and have not found anything that beats B&H, especially when considering the vig and opportunity cost. However, should one need to scratch the itch, timing strategies may work better with individual stocks. But again, opportunity cost.

Humbert H. writes:

I've always been believer in B&H vs. trading. But even in B&H the debate between indexing and individual stock selection never dies. I don't like indexing, but I don't have a mathematical basis for that. It's a fundamental belief that buying things without any regard to their economic value has to fail in time, at least relative to paying some attention to it.

Zubin Al Genubi adds more:

Another aspect of buy and hold that Rocky pointed out is the capital gain tax severely eats into returns. The richest guys hold for years and have only unrealized untaxable gains.

Art Cooper agrees:

There was an excellent article in the Jan 7, 2017 issue of Barron's by Leslie P. Norton on VERY long-lived closed end mutual funds which have surpassed the S&P's performance. They have all followed buy and hold strategies.

Michael Brush offers:

Far more money has been lost by investors in preparing for corrections, or anticipating corrections, than has been lost in the corrections themselves.

- Peter Lynch

Steve Ellison brings up an important point:

And yet trading is one of the focal points of this list. The way I square this circle is to keep most of my trading account in an equity index fund at all times. When I think I have an edge, I make trades using margin.

Larry Williams writes:

B&H is the keys to the kingdom, but…the massive fortunes of Livermore were short term trades despite his comment about sitting on your hands. Even the current high performers, Cohen, Dalio, Tudor etc use market timing. When I won world cup trading $10,000 to $1,100,000, it was all about timing and wild crazy money management. One approach wins big the other wins fast. A point to ponder.

Bill Rafter writes:

What we found in studying only the SPX/SPY is that in the long run a buy-and-hold yielded 9.5 percent compounded annually. That was from 1972 to recent. Our argument is that studies before 1972 are flawed. That 9.5 was great considering there were several collapses of ~50 percent. However if you could just eliminate the collapses you could raise the return to 13.5 percent compounded annually.

Eliminating the down moves did not involve prescience. You did not need to forecast recessions, only identify them when you were in one. That was not difficult, and timing was not a critical as one might think. We identified several algos that worked well.

When you were out of equities, you could either simply hold cash, or go long the 10-year ETF. The bonds were better, but not by much. Interestingly, long term holding of bond ETFs yielded low single-digit returns. Best avoided. Which also means that the Markowitz 60/40 strategy was a sub-performer.

Taxes are investor/vehicle specific. For example, if you use a no-tax vehicle, there are no taxes. Regarding turnover, there are very few transactions, as there are very few recessions. The strategy is basically B&H, but with holidays.

Asindu Drileba has concerns:

My problem with buy & hold Is that it has no risk management strategy. If you bought the S&P 500 in 1929 for example during the wrong month. It took you 25 years i.e until 1954 not even to make profit, but just to break even. The real question is, how do you know your not investing in a market path that will take 25 years just to break even?

Humbert H. responds:

That’s why, dollar cost averaging. I don’t think anyone thinks buy once in your lifetime and never interact with the stock market ever again. I think if you had averaged in monthly or quarterly from the summer 1929 through summer 1959 and then held and lived off dividends or cashed out/interest in retirement, you did well.

Art Cooper adds:

The year 1954 is almost universally given as the "break-even" year to recoup losses for buy & hold investors who bought at the 1929 peak. It's wrong to do so. First, it ignores dividends. Had dividends been re-invested the recovery year would have been much earlier. Second, it ignores the deflation which occurred during the Great Depression. In this column Mark Hulbert argues that someone who invested a lump sum at the 1929 peak would have recovered in real economic terms by late 1936.

I'm not arguing against dollar-cost averaging, merely pointing out a historical falsehood.

Hernan Avella writes:

What people should do while they are young and have human capital left is to leverage!

Life-Cycle Investing and Leverage: Buying Stock on Margin Can Reduce Retirement Risk

The most robust research, incorporating lifecycle patterns and relevant time horizons for long term investors tells us that the optimal allocation is 50/50 all equities, domestic and international. But most ppl don’t have the gumption to be 100% on equities.

Dec

19

Arithmetic vs geometric average returns, from Zubin Al Genubi

December 19, 2023 | Leave a Comment

How does the arithmetic average differ from the geometric average in measuring returns?

The arithmetic average calculates the average gain per trade without accounting for the compounding effect. On the other hand, the geometric average (CAGR) considers the actual compounding from start to finish, providing a more accurate measure of the actual return.

Can positive arithmetic averages lead to losses or ruin in trading?

Yes, even with a positive expected arithmetic average, losses or ruin are possible due to the risk of ruin and the increased burden in recovering from drawdowns, . Geometric averages, considering drawdowns and compounding, offer a more realistic view of potential outcomes.

From quantified strategies.

This is the path dependency issue. Conclusion is position sizing is important to avoid risk of ruin or catastrophic drawdown.

Bill Rafter responds:

You are almost there. Think: can these two means be used to identify anything else?

Kora Reddy adds:

also called volatility drag:

vol_drag = mean(x) - exp(mean(log(x)))

or an approximated formula

Volatility Drag = -0.5* (Volatility)^2

PFA useful leteratrue

Zubin Al Genubi replies:

The expectation and the maximum drawdown can be used to compute optimum f, the fixed fraction of capital to risk on each trade.

I read the article [on volatility drag] and disagree with it. Ralph Vince says that a system will experience drawdowns equal to f and that is the only way to the highest compounding resulting return. It is impossible to get the return without the volatility. Diversifying systems can counter balance drawdowns if truly uncorrelated.

It is non-ergodicity of trading markets that make the geometric mean more important. A loss is not a straight line down, but convex because it takes a 100% gain to recoup a 50% loss. The geometric mean captures this. Arithmetic mean does not.

Big Al offers:

Shannon's Demon, or rebalancing between uncorrelated assets (they claim it's "little known", but that is doubtful).

Kim Zussman contextualizes:

"Say, your fund is down almost every year. What value do you add?"

"We're uncorrelated! (with buy and hold)."

Aug

19

Is America winning? from Bill Rafter

August 19, 2023 | Leave a Comment

In response to the President’s rant, the data shows that Payroll Tax Receipt growth turned negative in March 2022. Despite an “almost” rally last Christmas season, the Payroll Tax growth has been negative the entire time. The data shows the current rate of decline at ~2 percent per annum. Given the vehemence of the rant, any government official who might be tempted to say otherwise might lose his/her career. Reminds one of “The Emperor’s New Clothes”.

Ayn Rand: We can ignore reality, but we cannot ignore the consequences of ignoring reality.

Bud Conrad comments:

Your work on taxes is the best I've seen. It is a bit of a tle cycle indicator confirming economic slowing. as seen in the standard government numbers below.

So has the government hidden that we are in a recession with cooked up numbers, say from understated inflation so real GDP looks more positive than it really is? and that unemployment is low from birth death over additions to jobs, and disabilities not in the workforce?

Bill Rafter responds:

IMO it’s misdirection. The government picks something on which they want us (and the media) to focus. Usually it’s the unemployment rate, which is determined by a poll, and then they have the birth/death adjustment (i.e. the fudge factor). So it’s impossible to get a definitive “just the facts, ma'am” story if the gummint wants otherwise.

Regarding leads/lags, the payroll tax receipts numbers are accumulated electronically. There have been days when Treasury was closed, but the data was released anyway (automatically). That data is released with a one-day lag from when it hits the Treasury bank account.

The raw Payroll Tax Receipts data just looks like static. To make sense it must be seasonally adjusted (it’s highly seasonal). That is why it is ignored by gummint and the media, because they do not know how to seasonally adjust the data. MRL and DB have shops that work with the data and their output is barely intelligible.

Stefan Jovanovich adds:

As Bill knows better than any of us, "employment" is the category box that compels the people writing the checks to add contributions to the American-Prussian scheme that protects the worker through unemployment payments. Neither self-employment (i.e. real estate brokers) nor independent contractor (Uber drivers) is a worker category that requires employment tax payments or has eligibility for unemployment.

Larry Williams writes:

I would argue, with vigor, that stocks predict tax receipts; it is not the other way around. Lead time is a little over one quarter. Stocks (red) lead receipts:

Steve Ellison writes:

Anecdotally, having been removed from a payroll a few months ago, I am having the most difficult job hunt of my life, not at all what I would have expected given the headline unemployment rate of 3.5% (I'm an experienced data analyst with a passion for finding truth and extracting insights that lead to actions and better business decisions. I have thorough knowledge of data warehousing, SQL, optimizing queries in big data environments, and data visualization). Boston Consulting, where I know a partner, laid off 20% of its workforce this year.

Despite the sanguine reports from the BLS, Pete Earle examined state-level data in May and found rising trends in initial claims for unemployment and in WARN filings (advance notices of layoffs as required by the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act).

Stefan Jovanovich comments:

There is also the problem of delay. The Census produces a count of the receipts of what they call "Non-Employer" entities using income tax returns. Everyone who is self-employed and reports income as an individual separate from any business dba and everyone who is an independent contractor falls into this category. Today the Bureau proudly announced that "we tentatively plan to release the 2021 Non-employer Statistics estimates in the spring of 2024."

Aug

10

The Count, from Duncan Coker

August 10, 2022 | Leave a Comment

Rereading the Count of Monte Cristo with my highs schooler, I am struck by the fact the all the virtuous characters are failures at business (ship owner, tailor, inn owner), while all the evil ones are great financial successes (currency speculators, war profiteers, state bankers). Of course the Count rectifies this. His fortune comes by way of a cardinal in Italy, a secrete cave and 14 years in prison. Perhaps the author's ( Alexandre Dumas) message is that every great fortune has a dark past. Maybe that was true in his day, but ones hopes that is not the case today.

Kim Zussman comments:

Socialism is as old as the bell curve.

Gyve Bones writes:

I'm reading this book too, and have found it really interesting. I picked it up because I'd seen two different film adaptations of the story, one starring James Caviezel, who a year later would portray Jesus Christ in Mel Gibson's "The Passion", and an earlier one from the 1970s. The two were so different in many details that I wanted to see the real story in the book. Both movies were good, each in their own way.

Like Les Miserables, by Victor Hugo, the Dumas story is about French society dealing with the ripple effects of the French Revolution. Both have heroes who are sort of New Christ figures. Both characters are unjustly imprisoned. In the case of Danton, the "Count", it was a case of a corrupt prosecutor during a time much like now, where Napoleon is in exile, and his alleged supporters still in France are being hunted down and imprisoned. It reminds me a lot of this nation, which has sent a former president into exile on an island off the coast of Florida, and there is an official inquisition into his affairs which is imposing punitive political prison sentences on his political supporters, and making it a crime to speak with the former president on the phone, in order to thwart any attempt to organize a campaign to return to office.

There's a point where the Count uses and extols the virtues of hashish which you might want to be prepared to discuss with your teenager.

Project Gutenberg has a very nice illustrated edition of the book available, which is helpful in imagining the scenes described.

I had trouble with the size of the illustrated ePub version for my iOS Books app on my iPad. It's 76 megabytes with the images included and it would crash the app. So as an alternative workaround, I downloaded the image free ePub into the Books app, and keep a web page open on the index of the images, which are named according to the page numbers in the book, and I view them as needed as I'm reading along.

Stefan Jovanovich responds:

Dumas pere was anything but a socialist. He was an aristocrat who was beyond snobbery and sentimentality. Good people regularly get screwed by thieves, frauds and liars; but then, so do the thieves, frauds and liars by each other. That is the "moral" of the novel. The Count succeeds in his quest for revenge by turning the bad guys against one another. He is a truly great figure, and the wiki page does him proper justice.

Dumas was neither a monarchist nor a Bonapartist. He was a republican and a Freemason. The novel makes that very clear; and it got Dumas in real trouble when a second Bonaparte became Fuhrer. Dumas had to flee France for Brussels, which also helped him escape his creditors. Read the wiki page; it is a beautiful exposition of an extraordinary life.

Full disclosure: One of the Stefan's weird (academics don't even want to discuss it) speculations about Ulysses Grant is that he was reading Dumas' novels when he was at West Point when he was supposed to be studying "tactics". Grant did not have a full duplex brain when it came to language and music; he taught himself to read German and French, but he found it impossible to speak or understand the languages when spoken. He loved music, but could not play it or read it as anything but notation (i.e. he could not translate the symbols on the page to sounds in his head). Hence, his joking about himself that he only knew two songs - one was Yankee Doodle Dandy and the other was not. The biographers all assume that because Grant had no verbal fluency, he had not read Jomini. He had; he also knew it was complete crap, but why say so except to start an argument? (Grant definitely did not have the legal mind or temperament).

Gyve Bones counters:

Straw men are easy to knock over. I did not assert Dumas was either a monarchist or a Bonapartist. In the same way, Hugo, son of a mother of the ancien regime and a father who was a Revolutionary, he was a melding of the two, and the novel sort of becomes a Hegelian dialectic about the synthesis which emerges from the thesis (the old order) in conflict with the anti-thesis (the Revolution). Jean Valjean is his synthesis, the New Man, a man of Christian virtues without Christ and the sacraments of the Church He founded.

Steve Ellison adds:

Dumas lived a high life and was chronically in debt despite having a number of bestsellers. I still remember one sentence from the book, "He was denounced as a Bonapartist …" It made me think that the first totalitarian society was Revolutionary France, but I hesitate to make such a sweeping pronunciation in the presence of Mr. Jovanovich. In any case, current efforts to make modern denunciations similarly career-ending are a grave threat to liberty.

Stefan Jovanovich agrees:

Great comment, SE. The French revolution - as an event - has a scale and complexity that can only be matched by the global war that began in Spain in 1936 and China in 1937 and ended in Korea in 1954. What Dumas was describing was its net effect: everyone in France had become so kind of spy and snitch. So, yes, it was the first totalitarian society; but you need to give the Citizen Emperor the same credit that Stalin and Hitler deserve for so thoroughly organizing the tyranny.

Bill Rafter offers:

Pardon me for coming in late to this discussion, but there is a mistake: The tailor was Caderousse, one of the three co-conspirators against young Dantes. That failed tailor then became the owner of the Inn at Beauclaire, who then murdered the jeweler. The Inn itself failed because its location was bypassed by a newly constructed canal. That leaves Mr. Morrel, who failed because he was in a highly speculative business (the hedge fund of its time) and was not diversified. However his successors in the business, Emmanuel and Julie were certainly righteous and successful. They retired to a nice home in Paris.

Stefan Jovanovich writes:

Not mine. Dumas was very much someone who believed that an honorable life was the only one worth living, whatever its financial costs or rewards.

Henry Gifford writes:

When I was growing up in a part of New York City that was populated by about half Christians and half Jewish people, almost none of the Christian adults owned a business – they had jobs. The one Christian adult that I knew owned a business did not attend religious services. All the Jewish adults owned businesses except a few that were involved in organized crime (professional level: state senator, state assembly, etc.).

When I was a child attending a Christian school, they made us sing a song that included the words “oh lord, do until me as you would do unto the least of my brothers”. I didn’t sing it, even though I was required to, as I saw it as a request for the all the worst things that happened to other people to all happen to me. As a child I thought this included blindness, loss of multiple limbs, leprosy, locusts (even though I wasn’t sure what those were) etc.

I have never had a mentor in my life. The closest I came were adults who advised me to “make sure you learn a trade so you will have something to fall back on”, who I made sure to steer clear of after I nodded and smiled and made good my escape. When I was 16 I asked my father what he thought I should do when I grew up. He suggested I go on welfare. I never asked again, or brought up the topic of what I was doing with myself, etc. When I was about ten years into writing a book, I showed the almost-finished version to my parents, figuring they should see it while they were still alive. The only comment they had was a harsh criticism of the grammar on one page, which they insisted I correct. The “incorrect” grammar was part of an insightful and charming passage written by Benjamin Franklin in the 1700s.

A few years ago I was walking past a Jewish community center near where I live in Manhattan. On the bulletin board outside I saw a schedule of upcoming lectures. One was titled “The Five Risks Every Entrepreneur Should Take”. I picture a member of the community that sponsored that lecture stumbling in business a little while being surrounded by people who are supportive, and who applaud the person for trying, and then for getting up and going at it again. I doubt any member of that community would ask the person who stumbled if she or he had made sure to first learn a trade to fall back on, or demand that children sing a song like the one I and my classmates were required to sing.

I still manage to do OK financially. Among other endeavors I own or am part owner of property in nine US states, soon to be ten, all worth much more than I paid (including the properties I am contracted to buy on Monday). And I have never “paid my dues” by spending years doing something I hate, or by gaining all the easily available advantages of being dishonest. But the Christian kids I grew up with? I can’t think of one who owns a business, and I can only think of two who likely have enough investments to carry them for long if they didn’t keep working at their job. And I can’t think of any who seem to enjoy or gain much satisfaction from that which they spend their day doing.

As for the emotional toll religion has taken on people over the centuries, suffice to say that someone once summarized the difference between the emotional state of veterans of the US military during WW2 vs. those who were veterans of the Vietnam War as the emotional state of Vietnam War veterans being the embodiment of the result of one generation of young men being lied to by their father’s generation. Likewise, young people being lied to about what economic decisions they ought to make, meanwhile a different reality is there for the seeing, also has its cost.

When growing up I spent time in Jewish households when I could, as the people there seemed to me to have an upbeat and healthier attitude, compared to the funeral home ambience I sensed in most Christian households. But, of course, most people growing up in the US do not have that opportunity, and fewer take the opportunity if available. Most are simply beaten down by the forces of religious insanity and stay down for life. Just today I was waiting for a train and a person nearby was shouting into her phone on speaker, describing in an upbeat tone her life that struck me as horrible, while she periodically mentioned that “god is good.” Not to her, I think, but I didn’t argue with her.

Bo Keely responds:

henry, this is interesting from our comparative angles. I’ll bet the few kids like u and I would say the same thing. as a child, I also rejected the ‘do unto others…’ because it included negative things.

i also had no mentor throughout life. when I eventually took a teacher test that required answering, ‘describe your first mentor’ I wrote about an admitted imagined mentor.

likewise, when I was sixteen, my mother asked, ‘what do you want to do in life,’ on receiving a selective service notice. It had never donned on me, so I replied, ‘be a veterinarian’ since that was my summer job. that’s how I became a vet.

and, i also have never ‘paid my dues’ to society figuring i never owed any. The only real money I ever made was in rental housing in Lansing, MI with a strategy of buy cheap complexes, fix them up, and rent to tenants receiving monthly checks directly deposited into my account. i still do well financially with 25 published books that sell, on average, one each per month. my financial secret of life is to have negligible expenses. I have gained satisfaction from each of dozens of jobs too, and never lived hand-to-mouth. it’s long-term gratification.

I have reacted to the lies of my father’s generation by retreating from Babylon into an anarchic desert town. each is an independent citizen who thinks god is a stinking mess in the sky, and one should learn in youth to take care of himself.

Kim Zussman adds a coda:

After the revolution apartments and land was confiscated and living arrangements made equitably* by central committees.

Los Angeles voters to decide if hotels will be forced to house the homeless despite safety concerns

*government jobs, military, connections, etc.

Jun

5

Payroll Tax Receipts, from Bill Rafter

June 5, 2022 | Leave a Comment

How are they going to paint this as a strong economy?

[Data source. -Ed.]

Andy Aiken responds:

It's not, but it gives the Fed a pretext to hold off on rate increases in an election year.

Vic adds:

46 leaked the numbers in his speech on Powell. they get the numbers several days in advance.

A reader asks:

Bill, how have ten year yields reacted in the past when the number is both negative year over and continuing to accelerate down trend? It seems this could be the catalyst that causes the long end to flatten out/rally as the Fed continues to raise the short? Does that hypothesis bear out in testing?

Bill Rafter replies:

Thanks for the question. I will not know until I test.

George Zachar asks:

oddly, the y/y% change in private eci wages has roughly doubled since late 2020, now at 5%. can you square the circle?

Bill Rafter replies again:

I will have to look at it. The payroll taxes are most the macro I can tap, so I tend to put their veracity on top.

Paolo Pezzutti comments:

I was hoping an Api could download the file from the treasury website. There are a number of Api's in Python or R to download datasets in json, csv, xml from FRED and other websites as alternative data to find relationships and regularities with stock index prices. Some of these keys are premium. I wonder if this approach provides real added value with respect to counting based on the idea that prices represent the synthesis of all market players actions and views.

Apr

3

Term structure of rates, from Bill Rafter

April 3, 2022 | Leave a Comment

When looking back at the term structure of interest rates, certain periods stand out: 1998, 2001, 2006-7, 2018, and now 2022.

That history is displayed here, constituting the 2yr, 5yr, 10yr and 30yr rates shown as month-end closes. Note that the 3-month bill rate has been omitted, and that the 2-year is emboldened. All of the periods show an increase in rates prior to the congestion, and all subsequently resulted in economic difficulty. From basic economic education we have learned the causative connection and indeed current political “Policy” seems to be in agreement.

Kim Zussman asks:

Do you think the long term downward slope could affect the forecast ability of yield curves?

Zubin Al Genubi comments:

Its along the lines of "don't fight the Fed".

Bill Rafter responds:

IMO, the downward slope is a function of the Fed essentially trying to remove the US economy from the free market. So (1) yes to Kim for the observation that it will lessen the effect, and (2) yes to Zubin for the always true observation not to fight the Fed.

Had I take the picture back farther, say to the early 70s you would have seen much higher rates (i.e. 21% for the 3-month), so that downward trend is a long one.

Dec

14

Food Item

December 14, 2020 | Leave a Comment

Bill Rafter writes:

I was recently introduced to RICE GRITS, which are broken rice kernels. Due to the increased cooking surface, these gems turn smooth and creamy quite easily. I have had my starter pack three Days and have used them three times; once for breakfast, once as an understory for a sautéed scallop dish and once for rice pudding. Absolutely delicious. Their micronutrition content is very close to Irish oatmeal, and they are a nice morning change.

I received my grits from https://www.deltabluesrice.com a multi-generation family farm in Mississippi. Their website has lots of recipes.

Most recipes for rice grits call for frequent stirring of the pot. Fine if you have the time, but I’m too busy. My variation is using a crockpot. Although that means no stirring, you are left with some burn spots at the bottom of the crock. They come off with soaking in dish detergent letting chemistry do the work for you.

My crockpot version goes like this: Put a pat of butter in the bottom of the crock, and then add 4-to-1 units of water (preferably spring) to grits. Set the crockpot on low and return in 4 hours. Add cream if you want the ultimate luxury. Note that with a timer you can run the process overnight and have them for breakfast.

Ken Sadofsky writes:

https://preview.tinyurl.com/yy7dkdp9

From the women: oatmeal, eggs n a fruit or sugar. For world athletes, I get carbs n protein from eggs but oatmeal has lil protein. The Scottish have a sayin though about their men, oats n steeds (escapes me)

A Japanese Zojirushi rice cooker has fuzzy logic and requires no stirring for whole grain oats, groat oats, I believe. Perhaps counter-intuitive, or obvious, is that this part of the Orient would find the easiest way of soing what they're suppose to be expert at.

Dec

1

Middle East Power Politics

December 1, 2020 | Leave a Comment

Another Bold Strike Against Iran - WSJ paywall

By

This “Commentary” in today’s WSJ is a good piece about Middle East power politics. It is a refreshing challenge to the fake news of Iran’s claims that the recent attack on its nuclear scientist was done remotely, being somewhat pedaled by AP.

Jan

5

Article of the Day, from Victor Niederhoffer

January 5, 2020 | 1 Comment

"A Clever New Strategy for Treating Cancer, Thanks to Darwin"

"A Clever New Strategy for Treating Cancer, Thanks to Darwin"

Relevant to big rises in a year in S&P?

Bill Rafter writes:

This is a fantastic article for anyone with cancer, particularly prostate cancer. Thanks for posting.

K.K Law writes:

A broader point is this is another excellent example of out-of-the-box thinkers and doers who create revolutionary innovations.

Dylan Distasio writes:

Unfortunately these innovations occur in spite of the current US system not because of it.

Gary Phillips writes:

Not unlike market analysis, the key to effective clinical observation is how the scientist conceptualizes the problem, and how he uses the information gathered. The dilemma presented with molecular targeted therapy using chemotherapy, is the very process that induces cell death (aptosis) can also promote (chemo)-resistance.This is quite the recursive paradox. Chemo drugs activate multiple signal transduction pathways which can contribute to either aptosis or chemo-resistance. One of the ways to circumvent this problem is to use a combination of drugs; employing another drug that targets the signal pathways that contribute to resistance. Of course, treatment varies from one patient to another, and the major challenge is to develop individualized therapy options that are tailor made to the patient.

Ever changing cycles and evolving markets dictate that traders must be agnostic and and adaptive. A tested, multi-variate approach tailored to the intrinsic nature of the current market regime will provide the best assessment of the market's context and offer the best approach to trading that particular market.

Dec

1

Go Champion Retires, from Jeff Watson

December 1, 2019 | 1 Comment

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65783969/515689380.jpg.0.jpg) A Go grandmaster has retired because he believes that computers can never be defeated. What does that portend for individual, human participation in the markets? Are humans who manually enter trades destined to go the way of open outcry? Can humans have an edge over algorithms?

A Go grandmaster has retired because he believes that computers can never be defeated. What does that portend for individual, human participation in the markets? Are humans who manually enter trades destined to go the way of open outcry? Can humans have an edge over algorithms?

Bill Rafter replies:

The following is guesswork. Anyone with a different voice is welcome to comment. (i.e., no need to flame)

I believe that the AI trading of the markets to date has centered on trades that have an almost zero risk of failure. Thus they have mainly worked in the extreme short run, mostly by picking off the marketmakers or the spread. There are many trading shops who do not permit their traders to take a position overnight.

Therefore if you wish to beat the algorithms you must pick a different venue, specifically longer-term trading. Maybe that's 4 days, and maybe it's 400 days, but it must be different from what the AI shops use. That of course means greater risk, but specs are in the business of taking risks.

Sooner or later, some of the AI people will invade this longer-term space, and they will do so by picking portfolios rather than individual stocks. But they cannot eliminate risk, and as long as risk remains, profit opportunities remain for the individual.

Larry Williams writes:

The basis of all profits is trend.

Trend is a function of time.

The more time in a trade the more potential for profits.

As long as losing trades are stopped out so they are not turned to big ones by time/trend.

Zubin Al Genubi writes:

I believe humans can still beat computers in trading. Maybe one human can't beat one computer, but the computers as a group will have a distinct behavior that can be regularized and gamed. Its the group dynamic, as even computers will tend to a group think. This is especially true if they are learning, and if they are reactive. The fixed systems are still pretty easy to beat because they are still beating the same old dead horses. I've found, as Larry mentioned, that a longer time horizon seems to work better now days. Hard to out speed the computers. Probably easier to out wait them. For example I seem to use 4 hour / day bars now rather than 5 min/30min bars in years past.

Laurence Glazier writes:

Such factors lean me more seriously to composing music than playing chess. What defines us as human?

Ralph Vince writes:

I posit that about 50% of all human action is a feint, a misdirection of the opponent, a lie. Camouflage is the dress code on the planet, and we have a several million year jump at the game of deception the machines must learn, must catch up on.

The machines are so-far, trusted–trusted not to lie or deceive. Once they do, how will they be able to compete with us i that higher arena?

Even in music, Laurence, a variation on them, a little bending around of a melody, is a feint, an indirect lie, as it were.

Laurence Glazier writes:

I've found fractal mathematical techniques of structuring music that have a ring of truth, however writing from inspiration, like painting from nature, must be a battle and a humbling one, with no concession to vacuous prettiness - nature's colour schemes seem always to work in the visual world, and I posit also in music, though I try to figure out more accurate methods of transcription.

Oct

16

Book Review: The Murderbot Series, from Bill Rafter

October 16, 2019 | Leave a Comment

I have recently finished a series of four novellas: The Murderbot Series by Martha Wells. The books are action/thrillers occurring in space sometime in the future. They also contain plenty of humor. What is particularly interesting is the attention to detail, and you will quickly learn that in the future certain things are too complicated to be entrusted to humans.

I have recently finished a series of four novellas: The Murderbot Series by Martha Wells. The books are action/thrillers occurring in space sometime in the future. They also contain plenty of humor. What is particularly interesting is the attention to detail, and you will quickly learn that in the future certain things are too complicated to be entrusted to humans.

In the future there are robots for just about everything, but the hero is a Security Bot detailed to protect a team of humans. The hero has managed to hack into his own controls enabling him to seriously outperform, as well as watch lots of entertainment videos. Of course, he winds up saving the somewhat naive humans from an overly greedy corporate entity. But it's the detail of the author that makes the story, reminding me of other great authors. If you are thinking of doing anything with AI, you should read this series as a primer of things to come.

Aug

24

Unreliable Times, from Bill Rafter

August 24, 2019 | 1 Comment

Our experience with the last two weeks of August has been that the period resembles the time between Christmas and New Years. That is, it's best not to get too excited about market action during this time. Of course the ennui is increased by the G7 meet and Jackson's Hole get togethers.

However the NFP to be released will profoundly disappoint with regard to job growth. We know this because the August NFP report is based on data thru August 16, which is already visible. Noting how all of the media is engaged in piling on this Presidency, those bearish numbers will be ballooned up quite a bit.

Kim Zussman writes:

A bad jobs report could be bullish for Fed watchers.

Feb

10

Shipping Rates, from Anatoly Veltman

February 10, 2019 | Leave a Comment

I wonder what Ralph, Larry, Bill and anyone with economic outlook have to say at this juncture. A quick 6-month drop from 1,800 to 600 is impressive: "Ocean Shipping Rates Plunge: Just a Blip or the End of Globalization".

I wonder what Ralph, Larry, Bill and anyone with economic outlook have to say at this juncture. A quick 6-month drop from 1,800 to 600 is impressive: "Ocean Shipping Rates Plunge: Just a Blip or the End of Globalization".

Bill Rafter writes:

Funny that you should ask, particularly today as I am writing a missive about that to clients.

The macroeconomic numbers show NO negativity. They look quite good. But of course, that's not the stock market.

This past week we have liquidated some individual equities that had given individual squirrelly signals, getting down to 75% long. They had been good longs and we were surprised when they had to go. We had not replaced them, mainly because the buy list was not impressive. But we were anticipating going back to 100% long Monday or Tuesday. That was before I reviewed the current situation today. Now we discover that we must liquidate another 5%.

The big surprise is that a number of the "lesser" indices have given good sell signals, meaning at the very least that a further rally is not imminent. In addition to those public indices, several of our own constructed indices suggest the market has overrun itself, meaning at least a pause. We may find ourselves liquidating our entire long position.

But to reiterate, the macroeconomic numbers are fine.

Dec

18

A View, from Bill Rafter

December 18, 2018 | Leave a Comment

With regard to fundamental (macroeconomic data), none suggest recession. If there is any suggestion, it would be for a market correction. That specific data (a longer-term view of Treasury tax revenues) is complicated because there are only four historical examples, not enough for reliability. However even that data seems to have run its course, as a short-term view of Treasury payroll tax receipts has turned up, meaning that the December Jobs Report will be more positive than expected. You might wonder how we know that when we are only halfway through December, but in reality the end date for that data collection is last Friday (the 14th), which is already available. So, expect some bullish data.

A quasi-fundamental piece of data we examine is the relationship between debt and equity. Specifically, we monitor the moving correlation of stocks with bonds. We view this as a fundamental item rather than a technical one, although it originates within the markets. The most bullish scenario is when both stocks and bonds are moving higher, which is not currently happening. But it is not convincingly so; it could reverse in a heartbeat.

Our technical picture is weighted more on the bullish side. Of particular interest is the calm being exhibited by the volume in options, both that of individual equities and indices, the latter being particularly used to hedge bets. In short, there is no panic there. So the players there are either foolishly complacent or simply not worried. We also monitor the sentiment difference between professionals and amateurs. It is quite clear that the amateurs are those who are in panic mode.

If we were to go further and examine breadth, specifically the advance-decline series of both issues and volume, that data has turned upward.

Our long-term experience is that whenever there is a disagreement between fundamental and technical factors, go with the technical. The technical items measure decisions having been made by real players, which does not always describe the fundamental items.

The real problem is political. We have a much different journalistic environment that we have ever experienced. Not only does the press hope to bury the President, but also the economy. Hence the rise of Socialist “stars”. We do not know how to deal with that, other than it is wishful thinking on the part of the Fourth Estate, a group that historically never invests. We would expect such wishful thinking to go unrewarded.

My apologies for the lack of charts proving my points, but there is just too much data to represent.

Nov

1

Shoe Shortage? from Bill Rafter

November 1, 2018 | Leave a Comment

I am always impressed with how speculation is crowd oriented. This is particularly true when one company in an industry is targeted for acquisition and its industry mates rise in sympathy.

I am always impressed with how speculation is crowd oriented. This is particularly true when one company in an industry is targeted for acquisition and its industry mates rise in sympathy.

OK, that's a given. However at this particular time there are a number of companies in the "footcare retailing" business giving similar signals. What happened? Did Americans wake up and realize that they were shoeless?

Sep

1

Flexion of the Day, from Victor Niederhoffer

September 1, 2018 | Leave a Comment

The flexion of the day stayed in Germany [8/30/2018]. Note how the Dax is down 110. Apparently they left for beer at 11. And the bunds are up 78.

Anatoly Veltman writes:

Note the reluctance to discuss or contemplate LEADING indicators that actually present economic sense. For example: everyone knows that EUR currency is associated with economic development and "order". While Swiss currency is associated with defensive posture and "calamity" hedge. The EURCHF pair doesn't move as much as other pairs in FX, because both currencies in the end are European currencies. Yet the pair has reversed since yesterday's SP record, and managed a straight 1% drop since…Now(?) Steve here is raising a possibility of a calamitous announcement over the weekend, but he wasn't raising it "before" the SP moved lower?

Cagdas Tuna writes:

Average short interest % to floating shares in FAANG is 1.64% and if we exclude Netflix it is 1.07% Does that kind of statistics provide any hint to market tops or bottoms?

Bill Rafter writes:

In our shop we have done a lot of work with short interest (SI). First, we noted that THE expert on SI (Erlanger) first identified "stocks to buy" and then screened them for any added benefit that could come from SI. Next, we worked the research from the opposite angle. That is, we first identified stocks with good SI potential, and then went on to screen them.

We were wrong. Apparently half of the stocks with high SI are truly good shorts. Of the remaining a relatively small percentage became good short-squeeze candidates. The others just went nowhere.

However we went further, studying stocks with extremely low SI. The theory is this: If you have a stock that even a damn fool idiot will not short, it probably means something. Assuming that certain fundamentals are unknown, we came to believe that it reflected on the quality of management. Of course we have no way of proving that, but still consider extremely low SI as bullish sentiment. That's intuitive, but at least we have some research to back it.

Aug

13

Reconciling the Data with the News, from Bill Rafter

August 13, 2018 | Leave a Comment

Reconciling macroeconomics and "job chatter", understand that the data do not support the enthusiasm of the news. Everywhere there are reports that the number of job openings outweigh the numbers of those looking to be employed. That may be the case, but the fact is that they are not being employed. Not yet at least. Maybe it is because the prospective American workers are unqualified (e.g. cannot pass the drug tests).

Whatever the reason, the jobs are not getting filled. That will change, but it may require some technology to assist the new workers. The trick is to make the job simpler for the unqualified, but no so much so that their jobs can be taken over by robots.

There are countries that have significant growth, and it is usually where the education system has provided the students with more than a sense of entitlement. Pardon my pessimism. We are actually quite bullish, but we would appreciate it if the numbers confirmed. Soon.

May

31

Anticipating Friday’s “Jobs” Report, from Bill Rafter

May 31, 2018 | 1 Comment

This is disappointing. It does not suggest a bad economy, but one in which the growth in jobs is proving quite stubborn.

Apr

11

Volatility Question, from Bill Rafter

April 11, 2018 | 2 Comments

In the last few days one of the economic talking heads commented on how he has "not seen volatility like this since" sometime in the past. I forget whether the former time was 1998 or 2008, but it doesn't matter, as there are many periods in the past with greater volatility.

My quick look at past volatility consists solely of looking at the height and duration of VIX in earlier periods. I took the standard measure (VIX) because of its relatively universal acceptance. I could use some of my own measures, but not without the risk of being flamed for subjectivity, despite the fact that they compare with VIX on a relative basis.

Question: Is there something I am missing? Is there some measure of vol that I am unaware of? Could the high volatility simply refer to the gentleman's equity balance? Could this simply be an effort to gain a headline, i.e. fake news? Any thoughts?

Gibbons Burke writes:

The VIX seems skewed to being more sensitive to downside volatility and not so much to upside volatility, and it is based on one instrument: the S&P 500 index calls and puts and their ability to speak to the volatility of the underlying index.

The standard Historical volatility calculation of the same underlying instrument used as the input for option pricing models is somewhat more flexible in that it can be applied to any instrument since all it requires is daily closing prices, and the S&P 500 retroactively before the VIX was created.

The two measures, VIX and SPX historical volatility correlate closely—and most interesting is when they depart from that correlation, which shows that the options market is anticipating something which has not shown up in the movement of the underlying. You know all this of course, and have developed some very interesting work on options and their open interest already as it relates to the underlying, no?

In technical analysis realms, average range, and Wells Wilder's Average True Range (which considers the previous day's close as part of the day's range if it is above or below the high or low of the day, which captures post-close volatility and gap moves) has been used as a volatility measure for input into risk allocation components in trading systems, and as breakout bands for trading systems like one made famous by Larry Williams and others like Steve Notis.