Oct

22

Government shutdown question, from Cagdas Tuna

October 22, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Are the furloughed government employees going to be counted as unemployed? I believe they will be which will be considered as a huge green light for 50bps rate cut in the December FOMC. This shutdown is the perfect storm for Trump’s “Fire Powell and get rates to 0%” scenario.

Bill Rafter responds:

The requirements for being “Unemployed” are that (a) the person is not working , and (b) that person is “looking for work”. I believe the latter qualification would disqualify those furloughed from being considered as unemployed. Not only the shutdown [will delay BLS releases], but the recently nominated BLS head, E.J. Antoni has withdrawn his name from nomination. So BLS is headless.

Alex Castaldo comments:

That is good news for all statisticians, I am sure he is a wonderful guy but he had a reputation for mistakes in calculations.

Oct

16

Hubris is going to a New All Time High, from Sushil Kedia

October 16, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Saudi Arabia has announced the Rise Tower that is likely to have a height twice that of Burj Khalifa! 2000 meters up from the ground! It is likely to cost 5 Billion Dollars. One is left wondering in a world where everyone manages to almost manages to get decent enough sleep every night with Trillion Dollar deficits, what is Hubris doing having been left so far behind!

Nils Poertner writes:

Wondering what to make of this though, Sunil. Saudi Arabia's main stock Index (TASII peaked in 2006. and never fully recovered properly. Any idea how to express it into some trading idea so we can test our hypothesis?

William Huggins comments:

The 2006 Saudis run is very similar to the soul al manakh run up 20 years before. In particular for Saudis though, it's a market that forbid ahoet selling so when the bulls got started there was no guardrail until they simply could find no bigger fool.

Nils Poertner responds:

Thanks William. Maybe one needs to look at oil (bearish oil story?) - oil doesn't move forever and then it moves a lot. (not an oil trader though - just something that came to mind)

Alex Castaldo offers:

For those too young to remember the events of 1981:

The Souk al-Manakh Crash

From 1978 to 1981, Kuwait’s two stock markets, one the conservatively regulated “official” market and the other the unregulated Souk al-Manakh, exploded in size, growing to the point where the amount of capital actively traded exceeded that of every other country in the world except the United States and Japan. A year later, the system collapsed in an instant, causing huge real losses to the economy and financial disruption lasting nearly a decade. This Commentary examines the emergence of the Souk, the simple financial innovation that evolved to solve its rapidly increasing need for liquidity and credit, and the herculean efforts to solve the tangled problems resulting from the collapse. Two lessons of Kuwait’s crisis are that it is difficult to separate the banking and unregulated financial sectors and that regulators need detailed data on the transactions being conducted at all financial institutions to give them the understanding of the entire network they must have to maintain financial stability. If Kuwaiti officials had had transaction-by-transaction data on the trades being made in both the regulated and unregulated stock markets, then the Kuwaiti crisis and its aftermath might not have been so severe.

Aug

25

Robert Z. Aliber, 1930-2025, from Alex Castaldo

August 25, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Friend of the Chair, Robert Z Aliber, a professor of International Economics and Finance at the University of Chicago, died in June 2025, I recently found out.

Just before the Financial Crisis (I don't remember the exact date) he sent a prescient Email to the Chair, arguing that problems caused by carelessly underwritten mortgages would soon cause a recession in the US. At the time I was not really aware of what was going in in the field of mortgage securitization, so I found the information surprising and was impressed later when it was confirmed by subsequent events.

Big Al adds:

Robert Z. Aliber on "The Next Financial Crisis?"

The University of Chicago

Apr 24, 2013

In 1982, 1997, 2003, and 2008, Asia and the world were rocked by major financial crises. Robert Z. Aliber discusses past crises and the possible trajectory of the next one. Where is the next major crisis likely to begin? How will its impact compare to previous crises? Aliber, a regular speaker for Chicago Booth, co-authored Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises.

Jun

13

Alasdair MacIntyre (1929-2025), from Alex Castaldo

June 13, 2025 | Leave a Comment

A few weeks ago I read about the death of Alasdair MacIntyre, described in Wikipedia as a Scottish American philosopher. And in some obituaries as "one of the great moral philosophers of the 20th century".

I heard his name here on the SpecList about 10 years ago when someone (sorry, I do not remember who, maybe GB?) recommended his book After Virtue, saying that it described how philosophy has gone wrong in the 20th century and how to correct it.

Intrigued, I bought the book, but like many things on SpecList, it was harder to understand than I expected. I think I read the 1st chapter or so, but I guess my knowledge of Aristotelian philosophy was not adequate and I could not make much progress. So the book sat on my shelf until now. I also did not quite grasp what Aristotle got right that later philosophers missed or what going back to Aristotle's views would mean in practice. The whole idea of reviving an earlier tradition seemed odd to me, I guess.

But still I am glad Daily Speculations made me a better person, at least judging by the books I claim to have (partially) read. Maybe someone else can explain it in terms I would understand.

Dec

29

Chance, luck, and ignorance: how to put our uncertainty into numbers

December 29, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Chance, luck, and ignorance: how to put our uncertainty into numbers - David Spiegelhalter, Oxford Mathematics

We all have to live with uncertainty. We attribute good and bad events as ‘due to chance’, label people as ‘lucky’, and (sometimes) admit our ignorance. In this Oxford Mathematics Public Lecture David shows how to use the theory of probability to take apart all these ideas, and demonstrate how you can put numbers on your ignorance, and then measure how good those numbers are.

Coffee cup he got from MI5 showing verbal-numerical scale they use.

Also: The Art of Statistics

William Huggins offers:

i like to give this guide to my students for whom English is a 2nd/3rd (sometimes 4th+ language).

Kim Zussman is unimpressed:

David Spiegelhalter was Cambridge University's first Winton Professor of the Public Understanding of Risk.

Translation: He is the most qualified of the vast array of those who don't know WTF they are talking about, but are knighted to tell us.

Peter Grieve responds:

I heard a story a decade ago about one of the big decision theorists, I think it was a Harvard professor. He was offered a position somewhere else, and was agonizing about whether to accept it. A colleague suggested he use his decision theory, and he said "Come on! This is serious!" I've no idea about the veracity of the story, or who was involved.

Alex Castaldo clarifies:

You are talking about Howard Raiffa. The story was told by another professor, although apparently Raiffa later denied that he had said it.

Sep

28

What is in Brooklyn?, from Asindu Drileba

September 28, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Lana Del Rey — My boyfriends really cool, but he is not as cool as me. Cause I'm a Brooklyn Baby. An interview recently posted here with The Chair — "I attribute your being humble to being from Brooklyn" (interviewer referring to The Chair). Another person I listen to - Such mistakes can only be made by people who have not spent a lot of time in Brooklyn. Brooklyn comes up so many times. What's is there to know about it? Of course I have heard of people talking about other cities.

But people that talk about Brooklyn always say it like there is something they know which others don't know. What is in Brooklyn? What does it do to people?

David Lillienfeld adds:

In the epidemiology world, when one of the organizations meets in Manhattan, inevitably someone will suggest to the younger members to go across the Brooklyn Bridge and experience Brooklyn. There is definitely something about Brooklyn that focuses one's thoughts.

Steve Ellison offers:

The Chair wrote a whole chapter on this topic, the first chapter of Education of a Speculator, titled Brighton Beach Training.

Laurel Kenner suggests:

Survivors go there when they get to America.

Alex Castaldo responds:

Agreed, immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe often arrived in Brooklyn as a first step towards success and acceptance in America.

H. Humbert writes:

There is a hierarchy among the real estate developers of New York. Those who develop real estate (especially large commercial buildings) in the central area (the island of Manhattan, also known as New York County) consider themselves socially above the multimillionaires who develop property in the boroughs of Brooklyn, Queens, Bronx and Staten Island. They refer to Manhattan as simply "the City" and seldom go to the other boroughs (other than to take an airplane at LGA or JFK airports, which are in Queens).

Donald Trump's father was a developer of large number of properties all of which were in Queens and Brooklyn and he considered Manhattan development too financially risky. He was quite wealthy but in view of the above was not considered a "major New York developer", like Roth, Reichmann and other well known names.

His son Donald was very ambitious and wanted to move up in society. Contrary to his father's policy he took a gamble and decided to put up a large building, the Grand Hyatt Hotel on 42d street in Manhattan. The project was completed in 1978 and Donald Trump joined the ranks of major NY real estate developers. (What the other developers thought of his operation is another subject and requires a separate article). Even if he wasn't fully accepted by all, when his daughter married a member of the Kushner family, another prominent Manhattan developer, a few years later, it confirmed that the Trump family had reached the first rank among New York's wealthy families. But Donald Trump, having overcome his Queens handicap and shown that he could do better than his father, was not quite satisfied and he decided to enter national politics.

In summary, there is a slight prejudice against people from Queens and Brooklyn, which sometimes causes people to be even more motivated to succeed and be accepted.

In addition Brooklyn has its own distinct accent, which causes the prejudice to be slightly greater. If you would like to know what a Brooklyn accent sounds like you can listen to any speech by Janet Yellen. When she was in line for a top job in Washington, a previous Treasury secretary (probably hoping to get the job himself) mentioned her accent as a reason she should not be appointed. She got the job anyway. Another success for Brooklyn.

Jeff Watson gets musical:

Steely Dan nailed it.

Aug

18

A Spec recalls fondly

August 18, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Back in the day, Chair treated spec-listers to a night of classical music at Lincoln center, then dinner at Picholine. It was an unsurpassed evening, especially in generosity. The last course was a cheese course, and the restaurant's cheese sommelier - Max McCalman - made a short presentation about the wonderful cheeses being served.

This was Mrs and my introduction to fine/delicious cheeses, which we enjoy to this day. Max showed us his book The Cheese Plate, and immediately Chair offered free copies to all the ladies in the room and asked Max to autograph them. The Cheese Plate remains a valued book in our collection.

Here is Max and an aficionado.

Alex Castaldo adds:

Yes, I remember that dinner well! Vic took guests to the best restaurants of New York in the early 2000s (Boulud, Le Bernardin, Picholine, Four Seasons, etc.). Those were great occasions, that I will always remember. Met some knowledgeable people, including Henry Gifford, on some of those occasions. Unfortunately I also remember that I never adequately thanked Victor for his generosity. Which I regret.

Jul

17

I don't have much knowledge of foreign exchange, although I admire and envy people like John Floyd who do. In 2017 I was interested in the idea of using PPP (purchasing power parity theory) to select countries that might be good prospects for stock investing over a 4-5 years horizon.

Looking at 2 different publicly available PPP rankings I noticed that SAR (South African Rand) was considered undervalued approximately 50% (!) on a PPP basis. In addition after several years of mismanagement the country seemed ready for a turnaround (bad policies cannot continue indefinitely). I purchased some shares of EZA (IShares South Africa ETF) in October 2017 at 59.36 usd a share.

Today, 7 years later, EZA is at 44.32 a share. More interestingly SAR is considered undervalued by 52.5% (on one of the 2 rankings, I can't find the other at the moment) and has been one of the most undervalued currencies throughout this period.

My mistake was not to do a thorough historical study of stock markets of countries that are undervalued on a PPP basis, and giving too much credit to the academic theory that PPP undervaluations are substantially corrected in 4 or 5 years time. Clearly some countries (eg Switzerland) can stay PPP overvalued more or less forever, and some like SAR can be consistently undervalued more or less continuously.

I learned my lesson.

Humbert H. writes:

I have been involved in raising private equity funds for emerging markets (Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa) since 2004. I have been specifically focused on Sub-Saharan Africa since 2017.

In my view and the view of others who I know that have been tasked with raising capital for these markets over the past 20 years, investors in these markets have not and do not get paid for the risk they are taking.

Nils Poertner responds:

maybe you are right on SA. am interested in the liquid stuff - and that is already a challenge in some of the EM markets.

Bruce Kovner used to say that most investors never really practise much imagination and test new ideas- they tend to go along with what others tell them - and then repeat the learned ideas (as their own). keeping this in the back of the mind everyday (even intelligent ppl forget that).

H. Humbert comments:

Investing in places where property rights are fundamentally not respected just isn't worth it because you can't calculate the risk. I've always considered Russia uninvestable, had one Chinese stock, would never buy any stock in a country led by a dictator. I do have a Mexican stock but in general avoid highly corrupt countries. SA is just too full of crazies to calculate the risk. The US love of sanctions and confiscations of Russian assets and the desire to impose wealth taxes endangers property rights and thus the overall level of attractiveness. At the moment, looking what happened in France, that makes it un-investable. When an Antifa leader leader on the national security watchlist gets elected to the National Assembly and and admirer of Hugo Chavez and Fidel Castro has a realistic path to be PM, watch out.

Henry Gifford responds:

Investing in places where property rights are fundamentally not respected just isn't worth it.

Indeed there is no need to look to outside the US to find examples. Just buy an apartment building in New York City and try to make a profit with the politicians telling you how much rent to charge. A politician looks at an apartment building and sees the owner as one vote, but the tenants as a large number of votes, thus the politician "buys" votes by "giving" low rent to the tenants. A few years ago the property owners in California lobbied for universal rent control on all properties, and got it, out of fear of a worse version passing into law.

In general avoid highly corrupt countries: In New York City it is impossible to get a gas or electric meter installed without a cash bribe to a utility company employee, and almost impossible to get any improvement to a building, including a single-family house, past inspection without a cash bribe to a city inspector. And the sanitation police who come fine store owners $250.00 for a cigarette butt or a leaf on the sidewalk (or on the street within 18" of the curb) have been reported paying their supervisors to assign them to areas with lots of stores, not single-family homes, so they can collect bribes for not fining the store owners $250/day.

Yes, it is possible to do honest business in New York, but it is very, very hard. I have never paid a bribe but don't make nearly the money I would if I did. Things are getting worse this way in New York City, which is perhaps the future of the US as the idea that our chair says has the world in its grip gets ever more popular.

I think Mr. Humbert's advice is very wise, but amounts of socialism and corruption are relative - find someplace completely free of both and I will move this afternoon.

Pamela Van Giessen suggests:

Wyoming might be the closest we get to corruption and socialist-free from what I can tell. Corruption, tho, is hard to uncover from a distance.

Dec

18

TLT follow-up, from Big Al

December 18, 2023 | Leave a Comment

TLT was way down since we discussed it at the end of August. Interestingly, HYG down nowhere near as much and still ahead of TLT YTD. My intuition would *not* be to see a narrowing of the spread between UST and HY.

Zubin Al Genubi responds:

Bonds have positive convexity, and will experience larger and larger price increases as the yield falls.

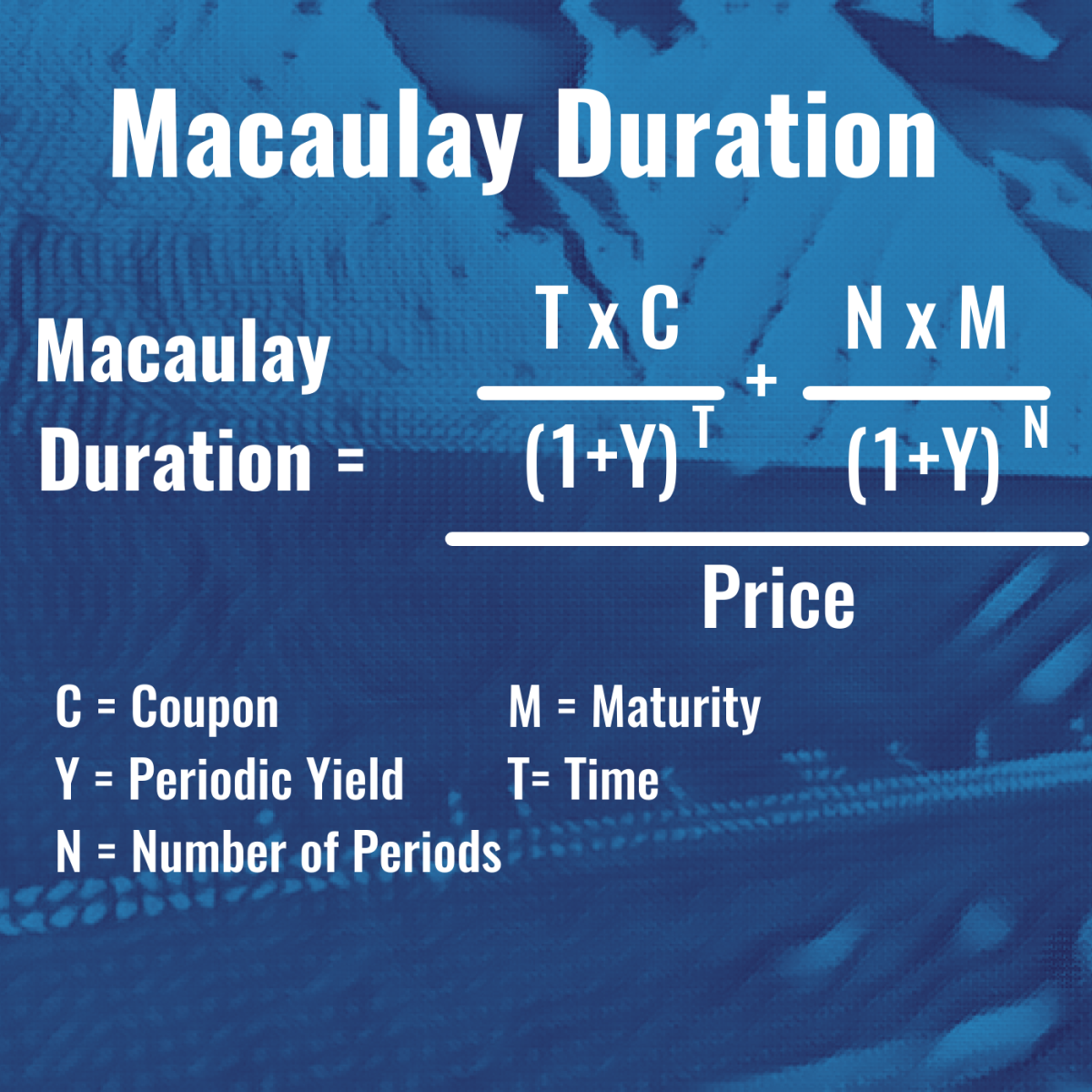

Alex Castaldo explains:

I am disappointed that the major ETF web sites (etfdb.com, etf.com, etc.) don't seem to give Duration values for Bond ETFs in a reliable and consistent way (sometimes they have it sometimes they don't). With a little effort I was able to find the following on 2 different sites:

TLT Portfolio Data

DURATION 16.11

YIELD TO MATURITY 5.19%

HYG Portfolio Characteristics

Average Yield to Maturity as of Dec 15, 2023 7.64%

Effective Duration as of Dec 15, 2023 3.37 yrs

Assuming these are both correct, up to date, etc. we can see that the Duration (responsiveness of price to yield change) of TLT is about 4.7 times that of HYG. And this is quite common when comparing high yield and high rating bonds (or bond funds).

Zubin Al Genubi adds:

Convexity, along with duration explains bank issues with rapid yield changes, and TLTs rise this month.

Dec

15

Why does Japan have a CA surplus? from Alex Castaldo

December 15, 2023 | Leave a Comment

Not for the reason I thought:

Japan’s current account surplus may not be a surprise to those of us who remember Japan as a major exporter. But a closer examination shows that the current account surpluses recorded today are NOT DUE TO THE TRADE ACCOUNT but rather the net primary income balance. Japan used the trade surpluses of the 1970s and 1980s to build up its holdings of foreign assets and prepare for the day when it would need income from abroad to pay for its aging population. Last year, according to The Economist, the country earned a net $269 billion on its primary income balance, equal to 6% of its GDP.

Oct

9

Remote viewing? from Nils Poertner

October 9, 2023 | Leave a Comment

For the military guys here- does remote viewing work? friend of mine - a statistician - who was tangentially involved decades ago- said what is striking: "those who didn't believe in it - scored worse than chance". Can imagine that.

I go with the notion it may work in rare cases - but when it comes to forecasting mkts - one may run into many new challenges. probably takes time and would require years of training. not exact science anyway. could help with overall intuition perhaps.

Alex Castaldo is skeptical:

"those who didn't believe in it - scored worse than chance".

Trying to salvage something from a negative experimental result. Reminds me of "Well, our anticancer drug failed in a large sample test, but it seemed to work for left handed women between 65 and 75 years of age. That's very promising". Shifting the analysis to a question other than what was asked.

Nils Poertner responds:

for trading (or life in general) - it is good to be skeptical- and don't believe anything that comes along. on the other hand, one wants to keep the option of some (pleasant) surprises that one does not know everything. Controlled RV was used by the Military to my knowledge. that itself is a hint it may work.

Eric Lindell asks:

were these controlled experiments where either the viewer or viewed were in a faraday cage? Personally, I think there are two possible outcomes statistically: chance and not chance.

I'd like to see a rigorous study of remote viewing by those who don't believe in it — with faraday and standard scientific controls. I'd be surprised if it held up. You would need an objective measure of similarity of appearance between viewed and vision — which itself would be hard to gauge — statistically or even anecdotally. The faraday control especially is key to identifying the question itself — let alone its answer.

Humbert H. writes:

I've seen at least two Sci-Fi type movies where the remote viewer is tortured by all the evil he can see to the point of not being able to live on. I would say there are enough people in this world who wouldn't be troubled by seeing evil if they can become really rich, so I would say there is no real evidence of statistically significant remote viewing.

Steve Ellison comments:

There is a huge problem in academia, where the paradigm is "publish or perish", of research that can't be replicated. A 1940 study by Rhine and Pratt that found evidence of extrasensory perception was the original poster child for this problem. A big part of the problem is the traditional significance cutoff of p = 0.05. That's a reasonable starting point, but when thousands of researchers are working at any moment, 5% of their studies will reject the null hypothesis purely by chance. It adds up to a lot of non-replicability.

I have often thought that an advantage for those of us who are scholars of the market is that we don't have any pressure to publish and hence don't need to force dubious findings into practice. Instead of a pat on the back for being published, we get a cruel but not unusual form of "capital punishment" if our backtests can't be replicated in the market.

Anders Hallen actually finds research for critique:

Stock Market Prediction Using Associative Remote Viewing by Inexperienced Remote Viewers

Jul

6

The Chair poses a question

July 6, 2023 | Leave a Comment

how has the evolution of regularities in markets made it much harder to beat the 52% accuracy that no sports better can achieve to break even? one way is the ever changing relation between bonds and stocks between years. what else?

Larry Williams writes:

Crude's influence on stocks [has changed over time]

Alex Castaldo offers:

The Great Financial Crisis of 2007 and 2008 revealed a number of regularities that (I believed) would be very profitable in the future, but careful monitoring of them after their discovery proved very disappointing to me. For example, trend following that would have gotten you out of stocks and back in during that decade did not work well in the Covid crisis with a faster decline and faster recovery.

Nils Poertner comments:

a mystery indeed - some folks have lousy accuracies (say sub 25pc) and still do well - since a few things they do on top turn out great, eg, the lousy equity trader who got into ethereum early enough (and out when others got into it).

Kim Zussman adds:

Yield curve inversion from 3 months and 500 points ago:

Hernan Avella comments:

Like sports, the evolution of markets is guided by the fitness of the players. We are not competing against prospective cab drivers trading in the pits anymore. But armies of highly talented people that invest thoughtfully and systematically in every step of the process: Infrastructure, trading business practices, research, execution, recruiting. I have a friend working in one of these highly capable groups. Around 70 people. All markets 24 hours, every single approach possible.

Very few of us from the old days survive. The Chair might be the oldest and longest lasting point and click trader. Such a great competitor!!! Ray Cahnman, founder of Transmarket Group is up there as well.

Vic replies:

the point-and-click survivor owes it all to Lorie and Dimson who taught there is a drift. also one learned not to succumb to conspiracies to margin one out.

Jared Albert writes:

Modern technology, particularly around real time customer segmentation and portfolio correlation, squeezed more value from the 'customer as the product' than before.

May

29

in what other areas, apart from financial markets and sports betting, is there vig? and what is really relevant for everyday life? and how to avoid it?

maybe we don't see it that way because of Gell-Mann Amnesia affect.

Hernan Avella responds:

There’s a rich literature on rent-seeking behavior. It’s pervasive, Pharma, Telecom, Agriculture, Natural Resources. Not all lobbying is RS but the majority is.

Vic asks:

is there a universal law of vig where it goes to 2% in all activities like sports betting?

Jeff Watson offers:

I wrote this in 2009 about vig:

The Vig Keeps Grinding Away, from Jeff Watson

Steve Ellison comments:

Games that advertise that they're commission free usually charge the highest vig of all …

Mr. Watson's statement was written well before all the retail brokerages offered commission-free trading, which I contend simply means convoluted execution that costs customers much more than the $7.95 commissions that existed previously. "Where are the customers' yachts?", indeed.

Separately, the way the CME evolved is a good example of the Professor's constructal theory that all systems evolve to increase flow and velocity.

Hernan Avella disagrees:

Your insights on electronic trading seem to lack sufficient grounding. Abundant evidence disputes your hypothesis, highlighting the significance of the percentage extracted rather than the total volume. The evidence is clear that more opaque markets, like credit and emerging debt, are more expensive, for everybody except for a selected group that invests heavily in keeping the status quo. Electronic markets are more transparent, more anonymous, standardized, continuous, centralized, offer multilateral interaction and informationally more efficient.

Zubin Al Genubi responds:

Give the evidence then, if its so abundant, rather than your usual vague negative comments.

H. Humbert comments:

The beauty of long term investing is there's no vig and there are no taxes, other than once or twice in a few years.

The origin of the word is interesting. It's a Yiddish corruption of a Russian (or some other Slavic) word pronounced "vi igrish" or "gain", but it's more like "winning in a game", and the root means "game".

Alex Castaldo adds:

Interesting. The word can be found in online Russian dictionaries.

"vigorish" has a similar pronunciation, though the meaning has changed to be the fee for the game instead of the winnings.

Nils Poertner writes:

we want to battle against vig in all aspects of our lives. almost build a register where there is vig and share it with family and friends.

Henry Gifford comments:

Vig is one of the many things I find it helpful to view with an understanding of the laws of thermodynamics. The laws of thermodynamics describe the movement of heat in the universe, and because all energy is either heat now or becoming heat, they could be called the laws of heat.

The idea of “follow the money” to understand a system or organization or relationship is closely parallel by “follow the heat”, and heat follows clearly defined laws.

In approximate inverse sequence to importance, the fourth law says that if things A and B are at the same temperature, and things B and C are at the same temperature, then things A and C are at the same temperature. This is also called the zeroth law because it is so basic it should have been thought of first. The fourth law reminds me of the unlikelihood of much true arbitrage existing.

The third law says nothing can be cooled to absolute zero, because that would require something colder to absorb the heat, and nothing can be colder than absolute zero.

The first law says energy can neither be created nor destroyed.

The second law, most analogous to vig, says that heat always flows from hot things to cold things, and never flows the other way on its own. This law is the most profound, with many implications.

For example, one implication of the second law is that a car engine cannot convert all the energy in gasoline to mechanical energy - some will leave as heat that is not useful (except for heating the passenger compartment during the winter). Vig. A utility power plant burns fuel and about 31% of the energy in the fuel gets to the customer’s electric meter - 5 or 10% transmission losses (heat escaping from wires is “lost” - see first law), the rest is waste heat at the power plant. Vig. Various devices can reduce the amount lost to heat, but these devices have too high a vig themselves.

Big Al adds:

The first law makes me think of markets (not the Fed or banking) where money is neither created nor destroyed. For example, in the FTX collapse, the media talked about all the money that was "lost". But of course it wasn't lost, it was simply transferred from one group of entities to others.

Hernan Avella critiques:

This line of thought fails empirically when looking at deflationary crises, loss of crypto keys, central bank operations, bad loans, bankruptcy.

Henry Gifford responds:

Loss of crypto keys and central bank operations both follow the first law - printing money leads to inflation (if inflation is defined as a lowering of the value of money), destroying some of the money in circulation by losing keys, or destroying a dollar left in the pocket of clothing getting washed, increases the value of the remaining money.

I have heard the term “deflationary crisis” before, but don’t believe there has ever been a crisis whose root cause is the increase in the value of money.

In the saving and loan crisis of the late 80s, lenders sometimes asked borrowers to make sure they borrowed enough to make the payments for two years, as it was taxpayer money being lent out, and the lenders were collecting enough vig to make it worth going under I s couple of years.

A bankruptcy stops wasteful behavior, and the threat of bankruptcy causes people to take steps to prevent it. But I guess the waste in a government can continue forever, apparently violating the first law, while also proving that a perpetual motion mechanism really can exist, violating both the first and second laws.

Larry Williams comments:

printing money leads to inflation—data does not suggest that to be true

Jan

2

Thoughts on EUR for January 2023, from Alex Castaldo

January 2, 2023 | 2 Comments

I do not focus on foreign currencies in my trading. And there are people here, such as Mr. John Floyd, who are far more knowledgeable about FX. So some of you may find these thoughts a bit simplistic; keep in mind I am an amateur!

I believe that a factor that makes a country's currency attractive to investors is the success (or lack thereof) that foreign investors have investing in the country in question. We can gauge this success by using ETF's that specialize in particular countries. For example SPY measures the performance of stock investors in the US, while EZU tracks investing in Eurozone stock markets.

What do we see? In recent months EZU has been performing better than SPY. For example in the last 6 months of 2022 SPY had a total return of 2.03% and EZU 9.56%. For 2022 as a whole SPY -18.38% and EZU -16.67%, two ugly numbers, but EZU did better. (These numbers will change between now and Dec 31, but not by much).

In my view this kind of comparison (especially given that Europe did poorly the previous few years, so it's a remarkable turnaround) will attract additional US investors to Europe, strengthening the currency. That is why I am bullish on EURUSD for the month of January 2023.

Bud Conrad responds:

Your logic is that if the stock market of a country rises, the currency of that country will rise in exchange rate. In the early days of this Speclist, the chair would ask me if I had "counted" the historical experience, which you cite for the last six months and year, but usually you need something like three cycles of inflection to get confidence.

The more usual comparison for currency strength are the Interest Rate Parity, using the futures market expected exchange rate and the difference in Interest rates.

And there the International Fisher Effect, also described here.

Often international traders look at trade balances for the country that has a trade surplus to be more attractive so the currency might rise. Trade surpluses mean they are a lender and not in debt to other countries. The US is the world's largest debtor, but the currency has been doing well.

John Floyd writes:

Doc makes the broadest, cleanest, and most accurate point about what drives currencies: what are expectations for return by BOTH domestic and foreign participants, and how does that drive investment flows into equities, FI, FDI, etc, which shows up in the BOP and Capital Account - on the other side of the ledge is the Current Account and the Errors and Omissions.

Admittedly I don’t know much about currencies and this is the area I know least about, but flow data is well researched and document by many at banks, independent research firms, IIF, IMF, BIS, etc. One challenge is it is often very much lagged, so Doc’s idea of looking at actual market instruments makes sense, and this is often particularly useful for emerging markets.

Capital account flows can fund a current account deficit for a very long period of time. Look at the US now or look at the Asian Currencies pre the crisis: errors and omissions become important given capital flight, particularly EM. Think Russia pre ’98 and Swiss bank accounts, etc.

As Doc well knows infinitely better than me, we need some more data and this can all be tested.

More broadly, outside of equity flows, Bud’s point of interest differentials will drive some capital flows. Also consider FDI from Europe to North America to diversify dependence on European energy costs and to friend shore manufacturing capacity.

And I would be remiss to not mention Italy (sorry Doc). Italy is in a Euro straightjacket that not even Houdini could get of. ECB is tightening with inflation at 10%, Italy 150% debt to GDP, Italian per capita GDP is barely higher than when joined Euro in 1999, Italy needs circa $250 billion in funding in 2023, 10 year yields in Italy up from 1 to 4.5%, all Italy issuance past few years was essentially bought by the ECB. This is not politically sustainable. Just look at the evolution of recent German politics. The ECB’s TPI is there but is intended for temporary dislocations and will require Italian political concessions. Oh and Italy is 10x Greece and the world’s 3rd largest sovereign debt market behind the US and Japan.

Read the full discussion here with additional contributors and charts.

May

29

Financial Analyst Journal, Vol. 26 No.2, pages 111-113:

The above Tables I and II […] show that the traditional Wall Street belief concerning the market's preference for Republicans is in accord with observed market movements surrounding Election Day.

If this Republican bias were justified, one would expect the market to perform significantly better during a Republican administration than during a Democratic one. To test this hypothesis, we looked at every year since 1897 and classified it by party in power and by its yearly position in the administration. The following table summarizes the results:

Year Republican Democratic

1 6.88% 10.35%

2 10.18% -1.21%

3 -6.84% 20.76%

4 7.15% 3.50%There appear to be no systematic differences in the performance of the market during Republican and Democratic administrations, except that during the third year of Democratic administrations the market performs significantly better than during the third year of Republican administrations. Thus, there appears to be no long term pattern in market movements which would justify Wall Street's Republican bias.

For those who would like to know: This article was written by Victor Niederhoffer, Steven Gibbs and Jim Bullock. It was published in the March-April 1970 issue of FAJ.

Zubin Al Genubi comments:

This year is on track with regularity. Will next year be up big contrary to all the bearish pundits?

Jan

19

Shipping Container Homes, from Bo Keely

January 19, 2022 | Leave a Comment

I’ve reviewed elaborate videos and glossy books on shipping container homes at the high scale end. It’s far simpler for cheap. I’ve lived in two containers in different valleys and it’s as easy as going to the bread aisle at the grocery store.

You go to the vendor – around the Salton Sea it’s the Calpatria hay store or trucking companies near the border. You pick out a used one from the lot, fork over $1-2000 that includes transportation, and lead the flatbed with your new home out to your place. The driver slides it onto pre-laid RR ties, you put a lock on the door, and celebrate the new home.

The biggest advantages are it’s difficult to rob, arson, or blow over like in the Three Little Pigs, and without building codes since it’s on skids.

I had no idea on moving into my first container in 1999 on the Sonora that I was looking into the architectural future. I installed a loft with waterbed, office with a solar powered laptop, and garage beneath a trap door. Chilled air rose from the garage through stovepipes into the interior and vented hot air out the roof. A satellite dish pulled in the Nature and History channels on an upside-down B&W TV. A pet packrat was a muse and road partner in search of gold in abandoned mining camps that it had been trained to retrieve. We drove two hours to sub-teach when mining was poor.

Then, in 2013, I owned the first container home in Slab City and am as content as a clam. There are three more now, the nearest scavenged and dragged from a bombing range target and riddled with hundreds of high-caliber holes. The second was towed from the Mexican border and is hemmed with painted flowers. And, the third was trucked from Los Angeles and converted into a church.

I thought I was on the vanguard of a would craze that is verified.

In the South Africa capital of Johannesburg, thousands of brightly colored boxes piled on and around each other, are stacked and re-stacked, and hauled away on trucks and freight trains, as homeowners decide where they want to live or sell. In Sudan, a prison is built of old containers slammed together. That’s how secure they are. Now container architecture is a hip fad in European cities for offices and homes. London has one of the biggest housing projects in the world of containers, and Amsterdam has the largest student village with over 1000 containers.

In USSR, shipping containers are used for market stalls and warehouses. Southeast Asia bazars are typically double-stacked containers. New Zealand earthquake rocked malls were rebuilt of shipping containers in the business districts. A Tokyo company provides container modules for multi architectural use. Prefab container homes are bomb across China. Google barges ply the seven seas with superstructures of stacked containers.

Shipping containers were invented in the USA in 1953 when trucking businessman Malcolm McLean gave a lot of thought when, frustrated by the glacial pace of overnight freight transport on the American highway system, he fashioned a set of stackable aluminum boxes and outfitted a decommissioned tanker ship to shuttle boxes of cargo up-and-down the eastern seaboard. In the next two decades, it spread over the oceans to other continents to radically change the face of global shipping. No longer does cargo have to be loaded and unloaded by a cadre of dock workers. Suddenly, the major cost of getting consumer goods around the world efficiently dissolved, and with it, many millions of boxes have been built and shipped, trucked, and trained, and now lived in.

Today, at any given moment, there are about 20 million more bobbing across the ocean or sitting in ports around the world. Union Pacific trains slide them three miles from my Conex home, and hobos know that a ride on a container train is a cannonball to any destination.

The sky is the limit. I think shipping containers will advance to fill into our architectural dreams for city projects, apartments, condos, hotels, and single housing units. Shipping containers are legal homes in California and elsewhere. They are cheap, built like a tank, fit the Golden Ratio, fast to construct, without codes, with high resale value, and can be moved as your heart pleases.

Alex Castaldo comments:

I have never lived in a container, but I would not recommend it. They lack the natural insulation properties of a wood or brick home, so they are chilly in winter and hot in summer. There is also the problem of no windows….

Larry Williams responds:

They work well here in the usvi where folks put 2-3 together for L or U shaped home.

Henry Gifford expands:

A steel box leaks almost no air unless doors and windows are installed in a sloppy way.

In rare cases, a building's heating and cooling loads are actually calculated before equipment is chosen. The job involves lots of measuring, and some simple math in the case of heating, and some fancier calculations for cooling loads.

Having calculated the heating and cooling loads of each room in many buildings over the years, I have found that very roughly half the peak and annual heating loads for a building are attributable to cold outdoor air leaking through the building, about one fourth is heat transmitted (conducted and radiated) out the walls and roof, with the other one fourth going out the closed windows. This is a rough generalization, but about equally true for old, poorly insulated buildings and new, very well insulated and airtightened buildings.

So, the lack of air leaking through a shipping container goes a long way toward comfort - it eliminates maybe half the heating load. And without the usual chemical soup of construction materials (glues, sealants, caulk, paint) in a normal house, the need for ventilation for health is reduced to a smaller amount. As few houses, old or new, are ventilated (few people open windows, as they also admit cold air, hot air, humidity, insects, rain, snow, and criminals), reducing the need for ventilation is a nice thing.

One way to explain the leakiness of normal construction is to point out that a person can hold a concrete block to their mouth (or a piece of a block) and breath in and out at a rate sufficient to satisfy the needs of an adult. I don't recommend vigorous exercise while trying this, but the point is that normal, sturdy looking materials leak a surprisingly large amount of air. The leaking is worse at connections between materials, and even worse than that at connections between assemblies (walls to roof, etc.).

Cooling loads are much more complicated mathematically because of the effects of humidity on indoor comfort, and because a cooling load calculation has to account for solar gain into windows (usually the largest part of a cooling load for a house), internal gains of heat and humidity from cooking, lights, showering, breathing, etc. Numbers for heat and humidity output from a bowl of soup or a lab mouse can be looked up, and are useful for calculating the cooling load on a restaurant or a medical lab.

The total lack of windows, or lack of numerous large windows in a shipping container goes a long way to keeping a shipping container comfortable during the summer.

Bo Keely responds:

You make the mundane details of buildings interesting, and this more than usual. The only air leaks in my container are fork holes where they loaded it over the years. This brought the price down to my wallet. I choose to not plug them near the roof as they vent the air in the summer. Where there is air, there is sound. My almost hermetically sealed box is soundproof. Also, roaches and rats can't get in. These are things money can't buy in Manhattan. I've never been so content.

Dec

27

Beating the Stock Market

December 27, 2021 | Leave a Comment

Beating the Stock Market, by R. W. McNeel (1926), could have been written by Graham in 1950 and contains the worst advice for customers that could have been given 1000 years ago and is still being given today: "Stocks are to be bought at low price - and only by so doing can one make money." the idea is that when stocks are low, people get frightened and at these times they would not think of taking money out of their banks and buying stocks. the idea is to sell when stocks are high, get out of the market, wait for the inevitable decline and then get back in. This is almost like it was written by Alan Abelson and his current day followers except that even after the 1987 fall where stocks fell 30% to Dow 400 the former was still bearish and called the decline a start.

What are the problems with this approach? (1) the market is more bullish at a new high than at a new low. (2) the stocks that go up the most have a higher expectation than the stocks that are down the most. (3) the market has a 10,000 fold a century drift upwards and thus you can never never be successful if you get out and wait for the "inevitable drop". (4) growth stocks perform much better than value stocks.

Other bad advice in the book which reads like it was written today is never buy new flotations as Rockefeller and Morgan lost money. Rock and Morgan lost money when they didn't stick to their list and invested in railroads. New Haven and Colorado Fuel and Iron were their downfall.

all these counter to the terrible and destructive advice in the book and other uttered today in the media must be tested. I will endeavor to provide such tests here in the near future.

here's a more current version of McNeel but the original book that Alan Millhone gave me as present was written in 1926.

James Lackey writes:

My immediate question is why are these books sellable? We realized they get published because as Pam might say that’s what book sellers do. She’s one of the many book published experts on this list.

Perhaps Vic's advice which is granite rock solid is that it seems too easy! To be honest I thought that as a young spec. Now I realize this:

It’s hard to be bullish all the time.

Everyone calls us fools.

Then they point out our faults.

If we dare share logic and my goodness statistical data to prove why we are bullish all the time they weaponize our insecurities. The bears are smart and have very good arguments. They can be spiteful mean men. I’d be an old mean SOB too if I was wrong on average about everything.

Alex Castaldo adds:

It has been more than 25 years since I read this book in the reading room of the New York Public Library and I don't have a full recollection of it. I went to read it because it was mentioned in another book (or article) by Dean LeBaron and the library seemed to be the only place to find it. At the time I was reading as much as I could about investing, both recent works and what others considered "classics".

The main point of the book I thought was the importance of independent thinking in investment. The author points out that most people are like sheep and follow what they hear from others. A good investor should guard against this and try to come up with his own judgements. If I recall correctly the author coined the term "contrarian investing" to describe this. He explained that "contrarian investing" does not mean believing or doing the opposite of what everyone else does or believes. Rather it means doubting what others believe and being willing at times (but not all the time) to take a different position.

I did not dislike the book. I did think it perhaps a bit too obvious. If you are going to "outperform the market" almost by definition you have to do something different than what everyone else is doing. Also, it may be easier said than done. Some people, such as the Chair, seem to be good at coming up with their own opinions, but most people are somewhat conventional and it is not clear what they could do to change. Would just being aware of the need to think independently be enough?

I also thought the term contrarian does not seem the best choice for what McNeel is trying to describe. (It sounds like mulish opposition to what everyone believes). "Independent thinking" or the term coined by Michael Steinhardt "variant perception" seem more appropriate to me. But still it was interesting to see what the originator of the term thought it should mean.

Feb

11

What Does Dr Burry Mean by His btc Mining Tweet Today

February 11, 2021 | Leave a Comment

Alex Castaldo writes:

what does dr burry mean by his btc mining tweet today

(20) Cassandra on Twitter: "70% of $BTC is mined in sanctioned countries, China, Iran, Russia. Crypto is in a race - add enough reputable agents of commerce to counter and overcome the inevitable coordinated actions of the ECB/BoJ/Fed/IMF/WorldBank-level powers-that-be to crush it. https://t.co/glYdmeTJ4g." / Twitter

70% of $BTC is mined in sanctioned countries, China, Iran, Russia. Crypto is in a race - add enough reputable agents of commerce to counter and overcome the inevitable coordinated actions of the ECB/BoJ/Fed/IMF/WorldBank-level powers-that-be to crush it.

Pete Earle writes:

He's saying that BTC needs to grow its network and become a more compelling medium of exchange in order to survive the likely outcome of the governments and monetary authorities in China and Russia (Iran?) putting severe criminal penalties on its mining and usage. Meh.

Does not follow that if mining were quashed in those countries other miners elsewhere wouldn't fill the gap, but it would be a bumpy ride and the price would almost definitely suffer. (There's also the remote chance that in the tumult that would follow miners going offline there could be a 51% attack.) But it strikes me that when an illicit enterprise becomes big enough (gambling, marijuana, etc.) governments would rather become privileged providers and gatekeepers than suppressors.

Jayson Pifer writes:

Burry seems to be missing that cheap electricity wins. It's not a matter of simply adding reputable agents when they will not be able to scale to compete with Chinese miners. Not to mention that those sanctioned countries are incentivized to mine heavily and therefore keep the security of the network high. I don't really see this changing.

I'm curious what sort of coordinated actions he supposes will be taken by the power-that-be. For the foreseeable future it appears to be concurrent debasement of currencies to the benefit of cryptos.

I forget who on the list was running a mining operation, the information shared was valuable. Perhaps we could get some recent insight.

Dec

1

Something I Noticed in The Tbond Futures Roll

December 1, 2020 | Leave a Comment

Alex Castaldo writes:

Last Friday was the day to roll long positions in ZB futures: to sell

the December futures (which are nearing expiration) and buy the March futures instead. I noticed something a little puzzling. For the last 2 years the far away (new contract) future was cheaper than the nearby one (the old contract). But last Friday it was the opposite:

> 2PriceDate old contr new contr oc price nc price roll cost

> 05/30/2018 ZBM8 ZBU8 145 14/32 144 19/32 - 27/32

> 08/30/2018 ZBU8 ZBZ8 144 31/32 144 7/32 - 24/32

> 11/29/2018 ZBZ8 ZBH9 140 4/32 139 16/32 - 20/32

> 02/28/2019 ZBH9 ZBM9 145 4/32 144 15/32 - 21/32

> 05/30/2019 ZBM9 ZBU9 153 2/32 152 14/32 - 20/32

> 08/29/2019 ZBU9 ZBZ9 166 2/32 165 8/32 - 26/32

> 11/27/2019 ZBZ9 ZBH0 160 3/32 159 10/32 - 25/32

> 02/27/2020 ZBH0 ZBM0 168 16/32 167 15/32 -1 1/32

> 05/28/2020 ZBM0 ZBU0 178 21/32 177 2/32 -1 19/32

> 08/28/2020 ZBU0 ZBZ0 176 14/32 174 25/32 -1 21/32

> 11/27/2020 ZBZ0 ZBH1 173 28/32 175 1/32 +1 5/32

As long as short term interest rates (repo rates) are positive, it would seem that an object delivered 3 months further away should be cheaper than the same object delivered 3 months sooner. (The good old Time Value of Money). Which makes me think that the Cheapest to Deliver for ZB March 2021 must be different from the CTD for ZB December 2020 if the March is priced higher? But I am not sure if this explanation is correct. And I find it disturbing that even though I traded tbonds for a while I do not fully understand some of the basic mechanics. Do you have any insight? Why did the price difference (technically know as the Roll Cost) flip like this?

George Zachar writes:

On Bloomberg, pull up USZ0 and USH1 CMTY DLV.

The cheapest to delivers did change:

Z0 = 4.5% '36

H1 = 5.0% '37

Nov

23

Change in Settlement Procedure for S&P Eminis

November 23, 2020 | Leave a Comment

Alex Castaldo writes:

BUT THIS IS NO LONGER THE CASE. Since Monday October 26, 2020 the CME always uses 4pm as the settlement time. So the 4:15 price and the settlement are now different every day, not just on the last day of the month.

Steve Ellison writes:

Thanks, Doc. I had done a double take a couple of times when the S&P 500 settlement price was completely outside the range of the last 15-minute bar. For example, on November 12 the range of the 16:00-16:15 period was 3543.75 to 3533.00, but the emini settlement price was 3532.50. Because I do intermarket analysis, I have long kept a separate database of each day's 16:00 price in the S&P 500 and other markets (US Eastern time).

Victor Niederhoffer writes:

more important what is the predictive properties of the move from 1600 to the real 1615 price

Nov

16

Views on Financial Transact Tax

November 16, 2020 | Leave a Comment

Alex Castaldo writes:

Hello fellow Spec Listers -

I'm curious as to anybody's informed take on the likelihood of the implementation of a Financial Transaction Tax, especially at a Federal Level - as this would quite materially harm our craft. Looking to learn more, and to prepare if necessary by pivoting asset classes / markets etc.

Kim Zussman writes:

https://som.yale.edu/faculty-research-centers/centers-initiatives/international-center-for-finance/data/historical-financial-research-data/st-petersburg-stock-exchange-project

Aug

24

American Odds

August 24, 2020 | Leave a Comment

Alex Castaldo writes:

On this web site https://www.oddsshark.com/politics/2020-usa-presidential-odds-futures the American Odds for Biden to win are quoted as -135 and for Trump +115

For those not familiar with America Odds here is how you convert AO to a probability

if AO < 0:

prob = |AO| / ( |AO| + 100)

else

prob = 100 / (AO + 100)

So the probability for Biden is 135/235 = 0.574

and for Trump 100/215 = 0.465

Richard Owen writes:

What is the origin of the AO format? It was deemed more accessible to punters to speak in terms of $100 units? Is the negative sign subconsciously in front of the favourite to dissuade people from betting the favourite? Old school bookrunners tended to be overweight the favourite winning, but now tend to be hedged?

Stefan Jovanovich writes:

I hate to disagree with Jeff about anything regarding gambling, but he is ignoring what he knows about hedging. The amount of money actually bet online on American politics is - at most - a tiny fraction of what is wagered on sports. The success of DraftKings alone confirms this.

https://sportsbook.draftkings.com/help/sports-betting/where-is-sports-betting-legal

The line on Predict-It and other politics wagering sites can be moved with a bet that will have zero effect on any of the dozen parlays that are offered for the next Liverpool match. Since the actual wagering does not need to be balanced by the bookies, they can set whatever line will attract the most attention and give them the most publicity and general traffic. Political odds are used the way Sam Walton used the stacks of peanut brittle when he started with his J. C. Penney stores. He put them on the sidewalk or just inside the entrance and the people walking/driving down Main Street have to take a look.

Biden and his odds are the peanut brittle. Odds favoring Trump would have the opposite emotional effect.

Jul

11

Coming back from behind

July 11, 2020 | Leave a Comment

Alex Castaldo writes:

Heres the skinny. from math puzzles volume 1, by presh talwalkar. doc here. from nature walk. originally to stretch aubrey's mind . odds of a comebak victory

Consider 2 teams a and b that are completely evenly matched. given that a team is behind in score at half time, what is the prob that a team will overcome the deficit and win the game. assume the first halve and the second half are taken to be independent events. Presh solves it as follows logically:

Since the two teams are evenly matched, it is equally likely that the team will score enuf points to overcome the deficit or that it will not score enuf points. fo example the event of falling behind 6 pts in a half game happens with the same prob as gaining 6 pts in a half game. He concludes prob is 0.25

Now we posted the empirical resutls from basektaball games and many others have given the empiriclal results for football games … and i gave some results for the markets.. this seems to be of interest to everyone , had the most views of any posts, and it was good for 7 or 8 points today.. lets have your discussion and solution of this problem. presh says the answer is 0.25 both empirically (NFL in 1995) and logically.

Jared Albert writes:

In a game with two teams where in the first round, the team 1 advantage varies from flat to all the points available in the second round, the probability of team 0 coming from behind to win are in array with 20 available points in the second round:

[0.49, 0.306, 0.22, 0.129, 0.09, 0.03, 0.018, 0.011, 0.004, 0.002, 0.002, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

For example, if the teams are even going into the second round with 20 available points, .490 chance that team0 wins; with a one point advantage to team1 at the start of round2, team0 wins .306 of the time;

2 points to team1, team0 wins .220 of the time etc

Here's the montecarlo:

import numpy as np

np.random.seed(10)

out_list = []

out_list = []

count = 1000

win = 1

lose = 0

team0_start = 0

team1_start = 0

size=20

def runs():

z = np.sum(np.random.choice([win, lose], size=size, replace=True, p=None))

return z

def outcome(team1_start, count = count, team0_start=team0_start):

l= []

for _ in range(count):

team0_end = runs() + team0_start

team1_end = runs() + team1_start

came_from_behind = team0_end > team1_end

l.append(came_from_behind)

#print(f'l: {l}')

outcome = sum(i > 0 for i in l)

return(outcome)

for i in range(size):

out_list.append(outcome(team1_start=i)/count)

print(f'outlist: {out_list}')

Victor Niederhoffer writes:

up your alley i think. we have done something similar for market with real empirical results. the unconditional prob is much less than20%

Stephen Stigler writes:

I am sure you know but I repeat anyway:

1) the simple calculations ignore correlation between teams.

2) they also ignore information on the distribution of changes

3) Calculations using the distribution of changes are not hard.

4) But the information about the probability of extreme events is not well determined so they can be inaccurate

5) In any case markets unlike sports are not zero sum games.

Nov

25

Neither One Nor Three But Two, from Kim Zussman

November 25, 2017 | Leave a Comment

Black was right: Price is within a factor 2 of Value:

J. P. Bouchaud, S. Ciliberti, Y. Lempérière, A. Majewski, P. Seager & K. Sin Ronia Capital Fund Management, 23 rue de l'Université, 75007 Paris, France

We provide further evidence that markets trend on the medium term (months) and mean-revert on the long term (several years). Our results bolster Black's intuition that prices tend to be off roughly by a factor of 2, and take years to equilibrate. The story behind these results fits well with the existence of two types of behaviour in financial markets: "chartists", who act as trend followers, and "fundamentalists", who set in when the price is clearly out of line. Mean-reversion is a self-correcting mechanism, tempering (albeit only weakly) the exuberance of financial markets.

See also: "the holy hand grenade"

Doc Castaldo writes:

"Black was right: Price is within a factor 2 of Value"

This goes back to a famous difference of opinion between Robert C. Merton and Fischer Black.

In trying to explain Efficient Markets to a student audience, Merton said that to him an Efficient market was one where prices are within 5% of true value 95% of the time. This was his subjective estimate of how efficient he thought the stock market was, and a way of communicating the idea of high but not perfect efficiency to the audience.

Fischer Black had a looser concept and said that to him, efficiency only meant that prices are within a factor of 2 of true value at least half the time. The rest was what he called "noise", i.e. random divergences from true value.

The problem of course is that these are only analogies and no one knows what the "true value" is and therefore how far away from it the market is.

Sep

14

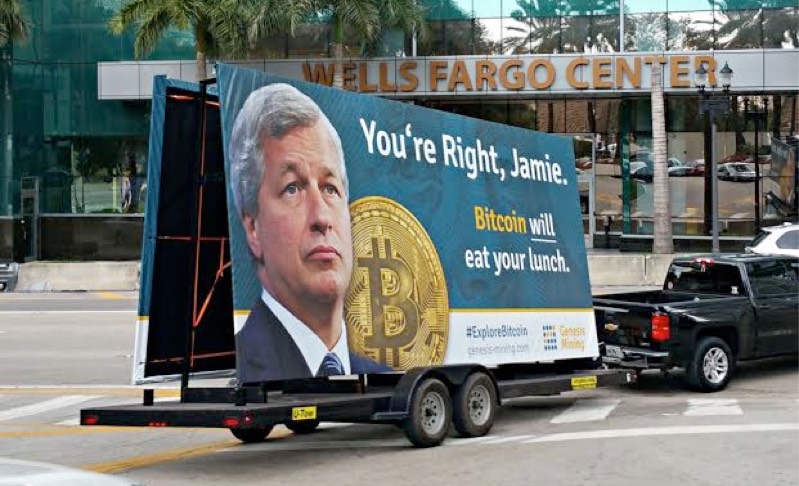

Jamie Dimon and Bitcoin, from Stef Estebiza

September 14, 2017 | 1 Comment

DIMON: BITCOIN IS A FRAUD

DIMON: BITCOIN IS A FRAUDDIMON: BITCOIN IS WORSE THAN TULIP BULBS

DIMON: BITCOIN WILL EVENTUALLY BLOW UP

DIMON: BITCOIN WON'T END WELL

DIMON: WOULD FIRE ANY TRADER TRADING BITCOIN FOR BEING STUPID

Andy Aiken writes:

And in response, bitcoin says that Dimon is a fraud…

Alex Castaldo writes:

Not very courageous either:

JPM's Jamie Dimon on #Bitcoin: "Don't ask me to short it, it could be at $20,000 before this happens but it will eventually blow up."

anonymous writes:

Mine, it's better ![]()

Aug

16

Turkeys on the Tennis Court, from Alex Castaldo

August 16, 2017 | Leave a Comment

Are these turkeys here to challenge Victor to a tennis game?

Mar

15

Why, from Victor Niederhoffer

March 15, 2017 | Leave a Comment

Why does Scholes say that option pricing is like crowd sourcing as opposed to the market itself? Also are option prices calling for a decline or rise? And are option prices generally right? If it were worth studying what Dr. Scholes wrote in detail, I would have many more questions but since he was well known I think as the weakest link in our program, I will not delve into it, possibly at my cost.

Why does Scholes say that option pricing is like crowd sourcing as opposed to the market itself? Also are option prices calling for a decline or rise? And are option prices generally right? If it were worth studying what Dr. Scholes wrote in detail, I would have many more questions but since he was well known I think as the weakest link in our program, I will not delve into it, possibly at my cost.

Alex Castaldo writes:

The article in question is

"Return to 'Old Normal' Hasn't Begun Yet: Scholes and Alankar After Trump's election, option prices signaled greater inflation risk. That no longer seems to be true." By Myron Scholes and Ash Alankar

I don't quite grasp what option markets are telling us, and how it relates to real and nominal rates.

Jan

2

Reduce Risk by Selling Vega? from Henrik Andersson

January 2, 2017 | Leave a Comment

Today I attended a lunch presentation with pension funds as the target audience. They defined risk as volatility and wanted reduce risk while maintaining much of the return. It was said that buying puts reduced return too much for most fund managers. The strategy presented was to reduce equity exposure from 100% to 50% and invest 50% in a low risk asset (short term bonds), at the same time sell both OTM calls and puts. They presented a back test of 10 years where the strategy outperformed index slightly while having a lower volatility (they outperformed during the 2008 crash and vol looked to be lower all along). I'd think they expose themselves tail risk by selling OTM puts, so was surprised they outperformed during the GFC and that they came out ahead. I still think they make it 'look' good during 'normal' markets but will get killed performance wise during sufficiently high upside and downside volatility–so I really think it is somewhat of an intellectual fraud to call this a 'low risk equity exposure' for pension funds.

Alex Castaldo responds:

I did not attend the presentation mentioned, but I am familiar with this kind of option selling strategy. One of the simplest is the PUTW (or PUTSM) strategy whose results are updated daily on the CBOE web site.

In the attached chart I compare it's total return since 1/2007 to the SPY total return (the S&P 500). Starting both strategies at an arbitrary level of 923, we see that PUTW falls to 690 in early 2009 (a 25% drop), while SPY falls much further to 503 (a 45% drop). What I find particularly interesting is how well PUTW holds up in the first half of 2008: while the stock market is going down PUTW manages to be steady or slightly up because it is selling puts at a high implied vol; only when the stock market begins to sell off very sharply after 9/30/2008 does PUTW also drop.

But even more interesting is what happens in March 2009 and after: the SPY begins to climb faster than the PUTW, slightly faster at first but markedly so after September 2012 and soon thereafter SPY passes PUTW. At the end of December 2016 SPY is at 1798 while PUTW is at 1668.

My conclusions are:

(1) The PUTW strategy has a lower volatility than SPY, both in terms of a lower drawdown in 2008 and a generally smoother path throughout the period (std dev of 11.5% per year versus 15.2% for SPY). The claims made during the presentation are believable. There is no intellectual fraud here.

(2) Everything has drawbacks as well as benefits. The drawback of PUTW is not that it will lose heavily in the future during periods of enormous volatility, but the opposite: that it will underperform during prolonged bullish periods for the market and probably over any sufficiently long period (long enough for the implied vol to adjust to whatever the situation might be and for the law of large numbers to take effect). So there is nothing magical here, as Dr. Zussman would say just the familiar tradeoff between volatility and return.

(3) The correlation between SPY and PUTW monthly returns is 0.85 (beta is 0.65) so PUTW is not all that different from SPY in terms of sources of risk (it is not a very good diversifier for stock market risk).

(4) The performance of PUTW is not theoretical or proprietary or reserved only for pension funds; it is explained on the CBOE web site (roughly speaking: sell 1 month ATM puts fully collateralized with cash) and since February 2016 there has been an ETF (also called PUTW) that implements it. So far it is small (30 million in assets). It has a 0.38% expense ratio, and so far has been tracking the CBOE version with accuracy that is quite respectable, and in line with expectations.

(5) Yes, you can reduce risk by selling Vega. Or increase risk by selling Vega, it is all in the proportions and how you do it.

Nov

14

The Future of International Trade and Investment, from Alex Castaldo

November 14, 2016 | Leave a Comment

Up to now the trade balance of the United States has been determined as a residual item, in other words it is not a target that policy makers and citizens look at but is the result of other variables like GNP growth, inflation, productivity, the value of the dollar, opportunities, preferences, etc. in the US and abroad.

Up to now the trade balance of the United States has been determined as a residual item, in other words it is not a target that policy makers and citizens look at but is the result of other variables like GNP growth, inflation, productivity, the value of the dollar, opportunities, preferences, etc. in the US and abroad.

If the Trump administration decides to target a reduction in the trade deficit (as seemed implicit in the campaign) that is a MAJOR change in how the economy operates and I wonder what consequences it would have. Is it even possible? Of course it is possible and many countries (such as Japan in the 60-70s, germany, china) have operated with such policies), but it is a big change in thinking for the US. My economics professors decades ago derided such policies with the epithet 'mercantilist' and refused to even discuss them ("it's not Pareto optimal, so forget it"). But at least some countries (esp. developing countries) have had some success with it as long as the ROW did not follow their example. We now understand such policies have some *benefits* as well as costs.

What form would the trade policy of the Trump administration take?

The most attractive would be an export promotion strategy, like the Asian Tiger countries. I have a friend who believes that the US should set up Special Economic Zones like the Shenzhen area in China, where special rules are applied to favor the establishment of new enterprises that are oriented to export. Low taxes, light regulation, waiver of union rules and so on would be targeted to a small geographic area (near an international transportation hub) with a view to boosting its productivity and export ability. It is a very Asian top-down approach and have some doubts whether this could be done in the context of Western decentralized, democratic and rule of law traditions. But there is an even bigger problem: where would the exports go to, when there are no longer any large developed countries available as export destinations.

The other strategy would be an import compression or 'onshoring production' strategy. This can be accomplished via Tariffs such as Trump has proposed but would have the side effect of raising the cost of products to US consumers. In addition because one country's imports are another country's exports it would result in a decrease in international trade. Since the mid-2000s international trade has been stagnant (after a period of high growth) so it would not be surprising that after Trump, Brexit, etc, it would turn down. What would be the investment implications of a fall in international trade and investment? Historical periods of decreased international trade are not exactly bullish for the economy.

As you can see, although I do believe the Trump administration will be the greatest and best, I have trouble seeing how the policies can be applied without causing major changes and some kind of negative disruptions in the world economy. I would like to hear from you any ideas how we can analyze the situation in a clear and practical way. What asset prices will be affected and how.

Anonymous replies:

My sense is that the Trump trade policy would work through tax incentives (like the tax incentives now offered by states to businesses who locate or stay there) rather than through tariffs.

West coast dude suggests:

Future increases in prices of consumer products as a result of switching to domestic production are already being reflected in the price of bonds, which are falling in response to higher expected inflation.

Aug

17

Palindrome Doubles His Bet, from Kurt Kurts

August 17, 2016 | Leave a Comment

Based on the timing indicated, he must be significantly underwater at this time. That assumes he has not thrown in the towel by now: "Soros Doubles His Bet Against S&P 500 Index"

Based on the timing indicated, he must be significantly underwater at this time. That assumes he has not thrown in the towel by now: "Soros Doubles His Bet Against S&P 500 Index"

John Bollinger writes:

The interesting question for me is: Why is he advertising this now?

Peter Tep writes:

Good point, John.

Sounds like he is releasing the hounds, so to speak.

Did the same for his short Aussie dollar trade some years back and also his long gold position–get long, get loud.

Jeff Watson writes:

The more important thing is, who cares what the Palindrome says he does. Whenever anyone who's purportedly a big player discloses his supposed position, I look at his motives with a big grain of salt.. People bluff in the markets as much as they bluff at final table of the WSOP. It's all a mind game, and while one should take in what the opponent says, keep in mind that their disclosure is not for your benefit and it could be a bluff. A good lesson is to look at announcements like this and try to find tells….they exist. Nobody ever discloses their position(real or fake) to the media to be altruistic and benevolent. The sad thing is that many people(retail investors, CNBC watchers etc) believe in the good will of the Palindrome and the Oracle to the small investor. Those same unknowing investors are the pilchards that are eaten by the sharks.

anonymous writes:

"keep in mind that their disclosure is not for your benefit"

That is a key. Even if it is true it is still not for our benefit. For example "they" cover while "we are riding a growing loss waiting for the idea to play out. Our entry was their exit. The flexions/greats/insiders see angles we can't, if we listen regularly our account balances will be eaten.

Petr Pinkasov writes:

I struggle to see how in 2016 it's even intellectually sound to present Q as another 'dagger on the steering wheel'. It's hard to quantify the intellectual capital that investors are willing to pay 50x earnings.

Alex Castaldo writes:

Exactly. What is the Q ratio for AAPL, how many factories do they own and how much are those factories worth in the marketplace? (Rhetorical question). The Q Ratio is a statistic from another era, when John D. Rockefeller built oil refineries bigger than anybody else's or when Mr. Ford bragged about his new River Rouge plant. It has limited value in many businesses today.

Another smaller point: the proposed tail hedging strategy is designed to break even if the S&P declines by 20% in a calendar month. In the last 30+ years (367 months) this has happened on only one occasion (October 1987). It is quite a rare event. Would you do this tail hedging all the time? I am not convinced that the numbers work when you consider that every month you are paying for put options.

Alston Mabry writes:

Alston Mabry writes:

Doing some searching, I ran across this on FRED:

Nonfinancial Corporate Business; Corporate Equities; Liability, Level/Gross Domestic Product

Cheap-seat question: I know what GDP is, but I'm not sure about "Nonfinancial Corporate Business; Corporate Equities; Liability". Is that simply adding up the liabilities side of the ledger for public companies? Actually, it peaks Q1 2000, so it must involve market capitalization.

But it does peak Q1 2000 and Q3 2007. Of course, ex ante how do you know it has "peaked"?

Ralph Vince writes:

All measures from an era when there was an ALTERNATIVE to assuming risk — that alternative now is to assume a certain loss, or, at best, a large rate markets exposure for the (slightly) positive rates at the longer durations.

This is an ocean of money that is coming through the breaking dam. It likely will go much farther and for much longer than anyone ever dreamed. Imagine the unwinding of the government-required-soviet-style Ponzi schemes like Social Security, which, at some point must start affording for self-direction to provide an orderly unwinding. Not only from the natural bookends of life expectancy, and pushing out the book ends to where too few could expect to ever collect from it, but the pressure from below in a runaway market for self-direction. This too will fuel the hell out of this run and make it last much longer than anyone dreams of.

Every equity that yields a dime has greater value than the certain loss; every wigwam that provides shelter too, from investing in the ingredients of pizza in Pulaski to Poontang in Pyongyang, all the wealth of the world must come out of the shadows and find a risk — and this creates a self-perpetuating feedback that is something we've never seen.

This is the move that comes along once in a century at best, and we're already starting into it. The measures of the world of positive rates (which may not be seen for a long time) I do not believe are germane to the world today.

Jan

14

Our Calendar Color Coding Scheme, from Alex Castaldo

January 14, 2016 | 5 Comments

Can you please outline the color coding rationale for the daily performance chart. I am confused on why some down days are red and the others are yellow..etc - A Reader