Jan

25

The Chair’s quest, from Peter Ringel

January 25, 2026 | Leave a Comment

Vic gives out a quest (a research quest).

I swear, I did see Vic's X post only afterwards. I too was thinking about the levels / rounds and how to test them today during my drive. Probably everybody is tired of starring at the same levels and so the mind wonders and wanders.

I am thinking of this approach:

utilize volume profile / volume per price level

(here a buffer bin can be applied / granularity from tick to x points)

(this will become important)

slice / bin the time series in segments of x

x needs to be defined,

I am thinking simple price ranges right now

normalize the segments

create a summary volume profile of all the segments ( an average or total sum )

plot it and hope something stands out

then a deeper statistical analysis of the volume profile, which is a frequency distribution

another approach could be to look at the "rejection power" of a price level after a crossing / touching event.

the crossing / touching events are often fuzzy in time

maybe remove time here a la range bars

after the event qualify the price range traveled for a fix time interval

so price-no-time vs price-time

Zubin Al Genubi writes:

The sample generally is biased bullish. Maybe take a look at bear regimes to see how hypothesis hold up. Also need to use unadjusted prices to retain rounds.

Peter Ringel responds:

TY. I am also thinking cash and virgin levels (around ATHs). the question of prices vs percentages will come up here too again.

If one sticks to prices and assumes an underlying behavioural cause of rounds, there probably are regimes with more or less black and white borders (fast transition) from 50 with weight to 100 with weight to maybe back to 50 in low volatility environments. Also the question, what difference does it make, if the index is 7000 vs 700.

William Huggins suggests:

it may be worth seeing if there are "liquidity cliffs" at rounds rather than sticky prices (order clustering as opposed to price clustering)

Peter Ringel adds:

The open interest at rounds at the option chain is usually noticeable higher vs all other steps.

Now I am thinking to look at the waning of these. Are they getting eaten up. Would explain the multiple crossings of a round needed till we get new ATHs.

Jan

14

Manipulation, from Humbert X.

January 14, 2026 | Leave a Comment

The allegation of “manipulation” is inevitably just code for “I just badly hosed a trade that seemed so good on paper.” Whereas the proper response to a bad trade is introspection and examination of one’s system. In the markets as elsewhere, there can be a general tendency towards the rejection of personal responsibility. This regularly surfaces in the “manipulation” allegation.

William Huggins responds:

not an opinion on anyone's trading but there is a "fun" bit of psych referred to as the fundamental attribution error in which my successes are the result of hard work and skill while the success of others boils down to luck. similarly, when things go wrong for me, its bad luck (or nefarious forces, "them") but when things go wrong for others, its their bad choices or immorality. pretty much every single person falls into this trap unless they spend a great deal of effort fighting back against the heroic narrative.

Humbert X. comments:

I find it does me little good to think about others, other than to identify when they are travelling in a herd and at an extreme level of emotion, for contrarian purposes. Though sometimes it is possible to learn from their successes and failures assuming they are being transparent about what went right or wrong, which is rare.

Nils Poertner writes:

Good to read Hannah Arendt on this note (free floating anxiety within any society have to go somewhere and sinister groups will use it for their advantage - if not a virus, then some other "Country-" Phobia, then climate change etc… So it would not be enough to change politicians , the anxiety is within the masses (and mostly unconscious).

The key for a speculator is to travel light in life and take things with a bit of distance (2 inches are often enough) - and focus on the process of making money!

Dec

29

A curious case of silver, from Anatoly Veltman

December 29, 2025 | Leave a Comment

So as Silver trades yet another stratospheric (psychological) target, there are a few questions. On commercial side, both Demand and Supply are price-inelastic. Whatever industrial uses are, Silver is hardly substitutable, especially at the time when other metals are just as pricey. And on new Supply side, much Silver gets out of the ground as a by-product from mines not primarily operating as "a Silver mine". So, again, Silver production can't be easily jacked up during Silver's rise.

On non-commercial side, however, it's the opposite. Supply/Demand balance works as it should. $77 (or $100 lol) market would cause Buyers to be abandoning bids; while grandmas might start dusting silverware off and storming pawnshops. Any other considerations?

Peter Penha responds:

Exactly - if you look at the Silver Institute Supply / Demand models it shows we have been in several years of deficits (still in deficit of course this year and next) - Mine supply peaked a decade ago

If you add up all the non industrial uses of silver (Jewelry, Photography+film (Chris Nolan & IMAX), and all silverware) they do not make up the deficit.

So in the Silver Institute model and I am talking 2023 $28 silver price we have some 20% of total ounces that need to be divested every year to maintain supply/demand.

60% of uses are industrial - solar is the future everywhere now….for those missing the US battery trade —> the Biden era tax credits for solar are now Trump credits for solar+batteries & the AI data centers are now going to be Bring Your Own Capacity and storage & connect to the grid.

Read the full post with additional comments.

Dec

12

Comments on free trade, from Stefan Jovanovich

December 12, 2025 | Leave a Comment

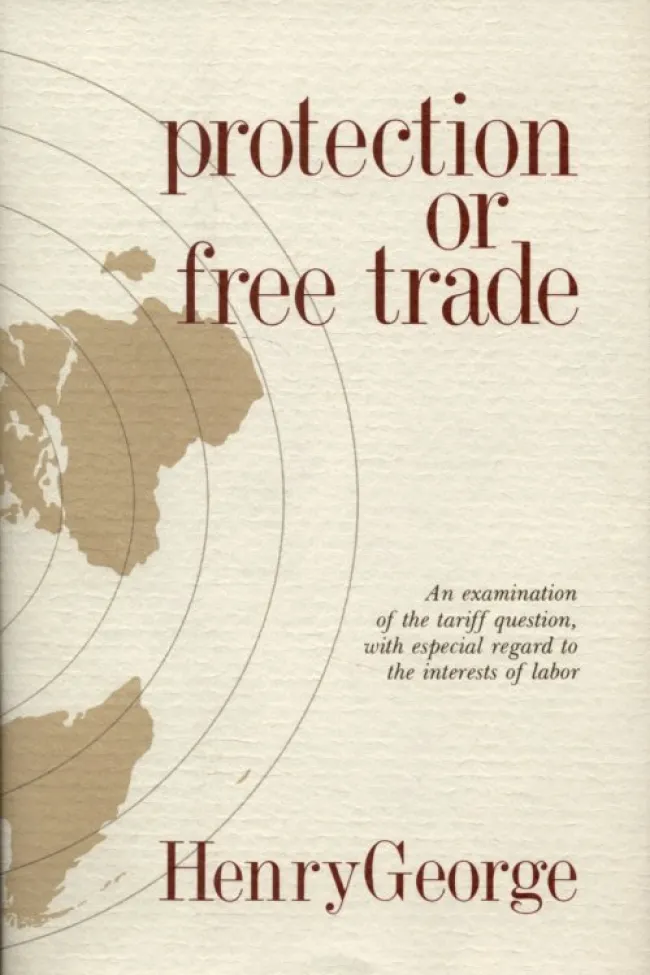

"Free trade" never loses an argument; it is like being in favor of virtue. Even the worst sinner knows that vice is not to be publicly defended. The difficult for those of us in the bleachers is that we have never been able to avoid asking the follow-on question: if you don't like tariffs as taxes, what do you want to have instead? Adam Smith's answers were (1) domestic excises - the sugar is allowed to arrive untaxed and then have a tax levied when it is sold and (2) occupancy taxes - to be measured by how many windows a building had. What is never mentioned, of course, is that Smith was completely in support of the navigation acts; Britain would have "free trade" but only on cargoes carried on British ships that traveled directly to British ports. His specific comment on that question was: “Defense is of much more importance than opulence.”

William Huggins writes:

i'm all ears to hear what national security threat the us is responding to with their 50% tariff on aluminum processed where there is an abundance of clean energy to do so and (until recently) all but perfectly aligned nat sec interests with the processor?

Stefan Jovanovich responds:

The answer offered by the authors and voters who made the Constitution the national law was "protection". I offer this only as an historical explanation, not advocacy, since those of us who live on popcorn and waiting from spring (what Rogers Hornsby said he did after the baseball season ended) have abandoned all attempts to understand what is called "policy", whether monetary or otherwise.

Art Cooper asks:

May I have your thoughts on Henry George's advocacy for the replacement of all other taxes by a land value tax?

Henry Gifford comments:

I think Henry George’s idea has a lot of merit, and not just because I heard that my father once taught at The Henry George School of Economics.

More than one calculation has shown that the cost of complying with tax laws in the US is about equal to the amount of taxes paid. If a land value tax eliminated all other taxes, almost all that cost would be saved. But, this would disadvantage the government because vague and complicated laws can be used by the strong against the weak, something not many in government want to see the end of.

Then there is the issue of jobs. The existing tax systems create a huge number of jobs, most of which would go away with a greatly simplified tax. Sure, those people could find more useful endeavors, increasing wealth for all, but if politicians started talking like that a lot of other things would be seen as folly.

Disagreements about the value of land could be handled like the ancient Greeks did – anyone claiming a lower value for their property can be challenged to sell it at that lower price.

A similar situation exists with the part of building design laws that regulate the energy efficiency of new buildings that get built. Now the laws run to hundreds of pages, which makes them very difficult to enforce. The vagueness gives the government people more power, as they interpret the laws as they see fit, or as they are paid under the table to do. For a time I was advocating a simple energy code: limit the size of the heating and cooling systems installed per the size of the building (you-tube: “The Perfect Energy Code”). Governments around the US were loathe to adopt a simplified energy code, because then jobs would be “lost” and the power to make arbitrary decisions would be reduced and the laws would actually be enforceable. A simplified tax collecting system will probably always be unpopular for similar reasons, despite what I think is a lot to recommend it.

Stefan Jovanovich responds:

Smith agreed with Henry George. He thought a land tax had all the attributes of a good tax, unlike income and employment taxes, which were the worst possible ones. Even tariffs had some virtues compared to those that required citizens to tell the state everything.

Oct

16

Hubris is going to a New All Time High, from Sushil Kedia

October 16, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Saudi Arabia has announced the Rise Tower that is likely to have a height twice that of Burj Khalifa! 2000 meters up from the ground! It is likely to cost 5 Billion Dollars. One is left wondering in a world where everyone manages to almost manages to get decent enough sleep every night with Trillion Dollar deficits, what is Hubris doing having been left so far behind!

Nils Poertner writes:

Wondering what to make of this though, Sunil. Saudi Arabia's main stock Index (TASII peaked in 2006. and never fully recovered properly. Any idea how to express it into some trading idea so we can test our hypothesis?

William Huggins comments:

The 2006 Saudis run is very similar to the soul al manakh run up 20 years before. In particular for Saudis though, it's a market that forbid ahoet selling so when the bulls got started there was no guardrail until they simply could find no bigger fool.

Nils Poertner responds:

Thanks William. Maybe one needs to look at oil (bearish oil story?) - oil doesn't move forever and then it moves a lot. (not an oil trader though - just something that came to mind)

Alex Castaldo offers:

For those too young to remember the events of 1981:

The Souk al-Manakh Crash

From 1978 to 1981, Kuwait’s two stock markets, one the conservatively regulated “official” market and the other the unregulated Souk al-Manakh, exploded in size, growing to the point where the amount of capital actively traded exceeded that of every other country in the world except the United States and Japan. A year later, the system collapsed in an instant, causing huge real losses to the economy and financial disruption lasting nearly a decade. This Commentary examines the emergence of the Souk, the simple financial innovation that evolved to solve its rapidly increasing need for liquidity and credit, and the herculean efforts to solve the tangled problems resulting from the collapse. Two lessons of Kuwait’s crisis are that it is difficult to separate the banking and unregulated financial sectors and that regulators need detailed data on the transactions being conducted at all financial institutions to give them the understanding of the entire network they must have to maintain financial stability. If Kuwaiti officials had had transaction-by-transaction data on the trades being made in both the regulated and unregulated stock markets, then the Kuwaiti crisis and its aftermath might not have been so severe.

Aug

27

Suppliers vs providers, from Stefan Jovanovich

August 27, 2025 | Leave a Comment

The opportunity lies with the supplier, not the providers of AI.

Larry Williams asks:

Who are the suppliers?

Stefan Jovanovich answers:

Nvidia. My 19th century brain thinks of NVDA as a supplier of the stuff the people selling information tickets will use to build their 21st century railroads.

Easan Katir writes:

Agree. Those creating the AI platforms won't generally be good investments, imho. Why? They lack one thing needed: scarcity. Any intelligent person can feed his/her data into an LLM and create their own AI for $20 / month or less. China's DeepSeek is free, I've read. Hard to make a profit when competing with free.

Last month I had lunch with an author cousin who lives in Tehama Carmel Valley. She uploaded all her books into an LLM, cloned her voice with another AI service, connected that to her voicemail. Now her clients can call her number and her cloned voice answers all their questions based on the knowledge in her books. All while she's having lunch.

AI + robotics will be a theme, such as Elon's Optimus and robo-taxis, yes? Investing in the suppliers is mostly done, isn't it? NVDA being the most obvious. Along with LW, other inquiring minds wonder which companies you have in mind.

William Huggins responds:

don't forget the coal and iron mines, those essential input assets that 19th century railroad magnates knew could be pilfered via land "grants". i think the equivalent is looking at the companies involved in the chip etching (who makes the lasers, etc).

Henry Gifford comments:

FRED says that Railroad stock prices weighted by number of shares went up x7 over 70 years [to 1929]. Nice, but not fantastic, but weighing by number of shares could be misleading because of reverse splits, shares of a new company replacing a larger number of shares of the old company in a buyout, survivorship bias when a company goes bankrupt, etc.

% of market cap can I think also be misleading because of people pouring huge amounts of money into companies with no revenue in the hope of future returns, adding to market cap.

Stefan Jovanovich responds:

In the last third of the 19th century, the money made in railroad investing was in the bonds, not the stocks. That was the recital of the FRED data that some found so surprising. For this 19th century mind those results are not surprising because the one President in the century who could do the math killed the speculation in international money.

Jul

23

Entry or exit opportunity, from Nils Poertner

July 23, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Donald Trump set to open US retirement market to crypto investments

President preparing executive order to allow 401k plans to tap broad pool of alternative assets

Hm. Entry for ordinary folks or a sneak way / exit for established players? Have a got a picture of the angel fish in my office, to remind me of the deceptive nature of markets. Angler fish are those ambush predator fish living in deep sea, that can illuminate poles in front of their jaws….to catch smaller fish.

William Huggins writes:

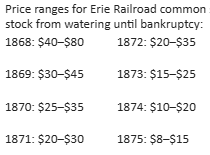

am reading Gustavus Myers' History of Great American Fortunes (1907) at the moment and just absorbed 300 pages of railroad fraud perpetrated by those who got their hands on the "mcguffin" asset and then sold it off only once they had successfully looted the value. the same sort of economic transfer happens for early crypto adopters - those trillions of market cap are "paper only" until some rubes can be fleeced of their efforts for the worthless securities foisted upon them.

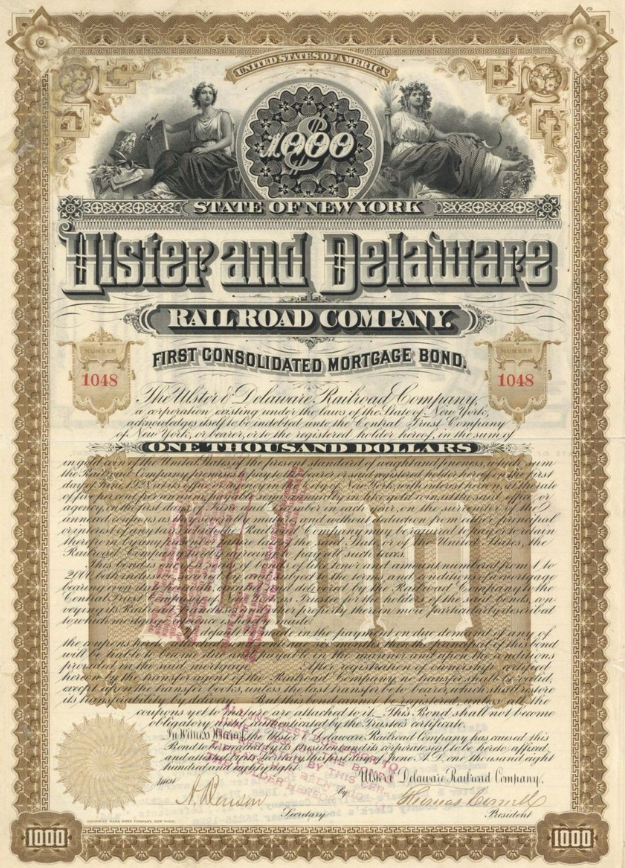

Stefan Jovanovich comments:

I hope this comment will not be read as argument or rebuttal but only as a factual footnote to Myers' work. The 50,000 shares issued by Fiske et. al. were "legal" in the same way that carried interest is "legal". They were allowed by New York State law in 1868.

The primary limitation on the issue of new shares of common stock for the Erie was its corporate charter. The board only had authority to issue $30 million in capital stock. Any issues above that amount required amendment of the corporate charter by the legislature and majority shareholder approval. The additional 50K of stock issued, at its par value, did not increase the total capitalization above the $30 million limit.

NY State law in 1868 allowed non-cash consideration. The contracts that the Erie board accepted as payment for the new shares were, in nominal dollars, fully equal to the par value of the shares issued. Shareholders had the right to challenge that claim; they were, as litigant frequently are, disappointed by the rejection of their challenge. The result was a situation that can be politely described as "judicial uncertainty" - i.e. a battle of conflicting injunctions.

Jun

3

Books again, from Asindu Drileba

June 3, 2025 | Leave a Comment

I can't find any books from the 1700s. Big events like the Mississippi Scheme and the South Sea Bubble happened in that period. But I can't find literature from the 1700s of people describing markets then. Maybe they had PTSD from having their fingers burnt? I heard Newton never wanted anyone to mention "South Sea" around him. (he lost his pile in the investment)

Stefan Jovanovich responds:

Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Général, by Richard Cantillon (1680s–1734)

During 1719 Cantillon sold Mississippi Company shares in Amsterdam and used the proceeds to buy them in Paris. Mississippi Company shares surged from 500 livres in January 1719 to 10,000 livres by December 1719; during the same period the prices in Amsterdam went from 400 to 7,000. The daily average spread is calculated to have been between 20% and 40%.

Carder Dimitroff suggests:

Empire Incorporated — The Corporations that Built British Colonialism, by Philip J. Stern

The book provides historical perspectives about British markets and corporate financing. It's not an easy read, but it is fascinating.

William Huggins writes:

there is a collection of "things written afterwards" about 1720 called The Great Mirror of Folly but its mostly moralizing tracts than a steely-eyed review of what went down. keep in mind the experience (a bubble in uk-fr-nl, all at the same time) had profound effects on the market for almost a century afterwards with the fr retreating from paper money and the british passing the bubble act which made it waaaay harder for anyone to raise capital. trading stock largely returned to being an insiders game until the 1800s. GMoF was recently published along with a pile of other primary docs by Yale U press:

The Great Mirror of Folly: Finance, Culture, and the Crash of 1720

I like the goetzmann treatment of 1720 from Money Changes Everything personally. He's got a couple of good recorded talks on it too. for those interested in institutional developments around markets and financial institutions in north america, I strongly recommend Kobrak and Martin's "Wall Street to Bay Street."

Steve Ellison offers:

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds was written in 1841 by Charles Mackay. The first three chapters are devoted to the Tulip Mania, the South Sea Bubble, and the Mississippi scheme. The remainder of the book is about non-financial episodes of irrationality, including a chapter about plagues that I re-read closely in March 2020.

May

30

The problem facing China, from Larry Williams

May 30, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Perplexity says it best:

The U.S. population is projected to keep growing through the end of the century, mainly due to immigration, even as deaths begin to outnumber births after 203325. By 2055, the U.S. is expected to reach 372 million people, with net immigration as the primary driver of growth. In contrast, China faces a rapidly aging population: by 2050, about one-third of its population will be over 65, and the number of elderly will vastly outnumber children, creating an “inverted pyramid” demographic structure. This aging trend is expected to slow China’s growth and strain its social systems, leading some to describe China as “becoming a nursing home” by century’s end. Meanwhile, the U.S., thanks to sustained immigration, will remain younger and larger than it would be from natural increase alone.

Asindu Drileba writes:

Professor Bejan's constructal law guarantee's that China will go bust on a long enough time horizon. I attribute this to China's rigid political system. Like Daenerys Targaryen said, "Those that don't bend, will break." Professor Bejan's TED Talk.

William Huggins responds:

for entirely different reasons, both Daron Acemoglu (econ Nobel 24) and Peter Zeihan are also in the China-bear camp long term - the former due to hitting the limits of "growth under extractive institutions", the latter due largely to demography (even if his tone is alarmist). Dalio's indicators suggest the opposite but all his data comes from a demographic regime of pyramids, not chimneys or inverted pyramids so i'm not sure his forecast will play out.

May

25

Atlas Shrugged, from Francesco Sabella

May 25, 2025 | 1 Comment

This morning I finished rereading the classic Atlas Shrugged of Ayn Rand and every time I learn something new; her thought is monumental. I don’t agree with a lot of her ideas and I fully agree with others, but I’ve always found this book to be an impressive catalyst for thought; this is in my opinion her power: the ability in sparking debate.

Rich Bubb comments:

Atlas Shrugged is also available as a 3-part movie. I think the book was better.

Adam Grimes writes:

My opinion on her work has shifted over the years, in a strongly negative direction. Too much of my experience contradicts her metaphysics and epistemology, particularly the rigidity of her rational materialism, and, as someone who treasures the craft of writing, much of her prose lands as clunky and overly didactic. I'm also now unconvinced on the primacy and sufficiency of rational self-interest… but, as you said, perhaps her greatest value is in creating discussion.

Asindu Drileba adds:

Ayn Rand had a reading group called the "Ayn Rand Collective" — Which Alan Greenspan was part of. They [Greenspan, Rand and a "professor"] would meet at Rand's apartment to read every new chapter of her new book. She (Ayn Rand) then fell in love with the professor and they started dating.

After sometime, the "professor" encountered a pretty young student in his own class and he "fell in love with her". The professor told Rand about the affair, but Rand begged the professor to cancel it. The professor then said that he would dump Ayn Rand, and then exclusively date the young pretty student. He said that this was the right thing to do since he was following his "rational self-interest". Ayn Rand got angry, slapped the professor in the face twice and kicked him out of her reading group.

This was a good illustration of cognitive dissonance. Rand thought her readers should practice "rational-self interest" towards everyone else, except her.

Francesco Sabella met a girl:

I was very fascinated to meet a girl times ago who I knew for her philanthropic activities and for her ideas being the exact opposite of Rand; and I was surprised to see her carrying an Ayn Rand book and she told me she didn’t like at all her; it made me think of her ability in creating debates.

Victor Niederhoffer responds:

i would always marry a girl who admired the book. susan introduced me to it and i knew then i had to marry her. it was very good choice.

May

20

Trend following, from Francesco Sabella

May 20, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Which are the flaws of trend following strategies? For me, the markets are homeostatic but not in a strictly way, they are like a thermostat trying to keep a room’s temperature steady. But, sometimes they can spiral into imbalance when people’s actions and beliefs feed off each other.

I’m amazed by how this dynamic of the markets has never been of particular interest in the academic world. It’s years since I don’t put in serious research given my focus on active trading, but unless something changed over this time, The classics wisdom is that markets are (let’s leave the perfectly efficient markets alone) in a perfect world supply demand state, I don’t remember having read of documented positive feedback loops etc, and overshooting and disequilibrium, which are clearly the case. I studied economics and I always found funny how some theories are.

William Huggins writes:

econ is not the right place to learn about markets because the demands of "equilibrium" require us to bend reality into the "preferred" (supposed logical) state. what most EM theorist missed was the friction in markets (adjustment time, imperfect info, etc). but momentum has been documented by financial theorists for decades. you're just digging in the wrong part of the field.

Francesco Sabella responds:

I know momentum has been documented, my point was about my economics classes, where I’ve never read about the topic, but also about how the mainstream academia is built - disequilibrium is not the classic wisdom and not even considered; you’re right that some academics have addressed momentum, but the mainstream economics is still fixated with equilibrium.

William Huggins adds:

econ likes equilibrium because its calculable, and because it approximates a physical science - if only those pesky active agents weren't so concerned about their perception of what matters instead of just obeying economists' assumptions!

in the end, its -hard- to math out the implications of imperfect, changing perceptions among a changing cast of strategically interacting characters when the targets are moving and trading may (or may not) be informed. because of these challenges, most prefer to stick to sanitized general equilibrium models, even if those are basically mathematical masturbation based on definable, stable, continuously differentiable utility functions. people usually find it expedient when modelling to pretend the net impact of all the above microstructure is "random" (its not really random, more like "too complex to model") within some defined distribution, which itself is a fudge but as Bachelier showed in 1900, might not be a bad one (and it helps avoid overfitting your forecast models).

here's are a couple of articles less than 30 years old on dynamic disequilibria (i cited Jegadeesh and Titman years ago so they were top of mind). the first talks about implications for macro, the second for asset pricing:

Towards a Dynamic Disequilibrium Theory with Randomness

May

13

A call for great new books, from Jeffrey Hirsch

May 13, 2025 | Leave a Comment

I am putting together a list of the Best Investments Books of the Year. I am not seeing many great books on trading, investing, finance, markets, crypto, options, futures, cycles, etc. I would love to hear if you folks know of any great books out in the past 6 months or so or coming soon.

Matthew Gasda is justifiably proud:

Big Al offers:

This is high-level quant stuff - ie, over my head, and despite "Elements" in the title - but a fun stretch:

The Elements of Quantitative Investing (Wiley Finance) 1st Edition, by Giuseppe A. Paleologo

His more basic 2021 book is "Advanced":

Advanced Portfolio Management: A Quant's Guide for Fundamental Investors, by Giuseppe A. Paleologo

Carder Dimitroff suggests:

This book is about historical finance and may not be a direct response to the question.

Empire, Incorporated: The Corporations That Built British Colonialism, by Philip J. Stern

William Huggins responds:

on a similar (historical) note, one of my students just recommended this title to me. looking forward to cracking it later this month:

Ages of American Capitalism: A History of the United States, by Jonathan Levy

Asindu Drileba adds:

If you would regard a speculator/investor as someone who also builds businesses:

Never Enough: From Barista to Billionaire, by Andrew Wilkinson

Andrew is building Tiny. His intention is to build the Berkshire Hathaway of Tech and software. He is inspired by Monish Pabrai (The Dhando Investor). So he is more in the "Value investing" camp not really quantitative.

Apr

26

Book question, from Francesco Sabella

April 26, 2025 | Leave a Comment

Does someone have a great modern macroeconomics book to recommend?

William Huggins responds:

it depends how theory heavy you want it to be. the author i usually recommend is Mankiw but Williamson (intermediate) and Romer (advanced) are good too depending on your needs. for the best "whole picture" i like a CFA publication from 2013 called Economics for Investment Decision Makers, by Piros and Pinto, which gives a great summary of micro, macro, and int'l econ under one roof.

for single-day-beach-reading i bought a casually interested buddy a copy of How Economics Explains the World, by Andrew Leigh, which is a great intro for non-users.

Apr

24

Planck’s principle, from Nils Poertner

April 24, 2025 | Leave a Comment

A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it…

An important scientific innovation rarely makes its way by gradually winning over and converting its opponents: it rarely happens that Saul becomes Paul. What does happen is that its opponents gradually die out, and that the growing generation is familiarized with the ideas from the beginning: another instance of the fact that the future lies with the youth.

— Max Planck, Scientific autobiography, 1950, p. 33, 97

relevance of how new ideas are being adopted in science, markets, everywhere.

Jeff Watson responds:

Science by consensus is not science. Just ask Galileo.

Pamela Van Giessen writes:

John McPhee wrote extensively about this and how the science of geology advanced over a few centuries in Annals of the Former World. Scientific community consensus is pernicious, and it is clear that there is mostly no convincing it.

William Huggins comments:

the foundation of science rests of replicability - anyone with the same data should be able to replicate results (even if they disagree about the mechanism). once replication is established, the difficult questions come from "is this data sufficient and representative?"; "is the data generating process stable or dynamic?"; "did i gather data in support of my hypothesis or to try to disprove it?". the fun stuff.

philosophy of science ensures we ask good questions and have good tools to tackle them with. this is why the Ph in PhD is short for "philosophy."

correction: "same data" is the wrong phrase - "equivalent, out-of-sample" would be a better choice of words.

Asindu Drileba writes:

The problem with the human mind is that it has too many glitches. You can verify data successfully and still be wrong. Here are two examples from Astronomy. First, The Mayans had models that would accurately predict eclipses. So, your data of when eclipses occur would replicate really well with their model. However the model of the solar system the Mayans used, had the Earth at the centre and the Sun revolved around it. The assumptions of the model were completely wrong, but the data (predictions) were accurate.

Second, is Newton's models, that predicted the movement of a comet accurately. Then you often here people say that Einstein proved Newton wrong with Relativity.

I think when it comes to science, explanations are very flimsy. What should matter is if the idea useful or not.

Francesco Sabella responds:

I think it’s a very good exercise to start from the point of view that our mind is bound to make mistakes, have glitches and start to work from that assumption; even if it’s not always true but it can be good as working hypothesis.

Big Al recalls:

Years ago, doing simple quantitative analyses to post to this list, I learned that one of the biggest pitfalls was my own desire to get a nice result.

Apr

16

The Invisible Gorilla in the Room, from Stefan Jovanovich

April 16, 2025 | Leave a Comment

That is the creature Hugh Hendry - the Acid Capitalist - says we have to find in order to profit from our speculations.

The events in Ukraine are that gorilla. They are predicting the likelihood that Trump, Putin and the Muslim oil producers will establish a Drill, Baby, Drill world of orderly energy production and supply priced in U.S. $. The effects on the European and Asian consumers will be comparable to what happened to the German-speaking world and its silver standard when the French fulfilled the terms of the Treaty of Frankfurt by paying their reparations in gold.

Big Al needs some help:

Perplexity answers the question, "What happened to the German-speaking world and its silver standard when the French fulfilled the terms of the Treaty of Frankfurt by paying their reparations in gold?"

Stefan Jovanovich answers:

They = "events, dear boy". The prediction is that the new cartel of oil and gas exporters will establish "orderly production" that manages the risks of overproduction in the same artful manner that OPEC once operated before the invention of fracking.

William Huggins responds:

So you are suggesting us producers will submit to directives from moscow or Riyadh to limit their production? No evidence of anything but predation among those players but somehow trump purs them all on the same page? I have a bridge for sale….

Apr

5

Time for the canes?, from Doug Martin (Updated)

April 5, 2025 | Leave a Comment

I'm liking the look of that huge spike down in ES, out of my euro and sterling, that was a crazy move too. Technically it's nice looking low, from a chart perspective. I'm liking the low interest rate and commodity softening posture, I'm pretty damn bullish on equities.

William Huggins responds:

the shock moment is not when the canes come out - those metaphorically come out when the bulls have given up. those are generational moments related to the culling of new speculators who have only known rising markets (ie, anyone who joined robin hood with their stimulus checks in hand). as long as there are people willing to pay x60-100 earnings for hype, i don't think its quite time for a shift in strategic allocation.

this is simply the first serious wakeup call for anyone who thought this administration is doing anything remotely like macroeconomic analysis when it sets policy. according to the executive, there will be more such shocks to come so as many were fond of suggesting in mid-november "buckle up" (your 401k, and the usd, have both been liberated from gravity!)

Steve Ellison comments:

The S&P 500 has not even gone off the bottom of my hand-drawn chart. The move down since yesterday strikes me as more an efficient market repricing of reduced economic prospects than an emotional panic or forced selling.

By contrast, my hand-drawn chart on February 28, 2020.

Adam Grimes states:

Canes? Nowhere close, in my opinion. And the fact that many people think this is a crash is just a lack of perspective (and a misunderstanding of potential.) Again, all in my opinion, which may change with any tick.

UPDATE: Stefan Jovanovich has a shopping list:

The idiot list is the catalog of companies that our model collects on the presumption that their common stocks will be worth more in 5 years than they are now. I publish it when we guess that our stupidity is within the 25% range - i.e. we won't lose more than $1 out of every $4 we invest in those companies if they liquidate. Thanks to the List and others, we have learned not to trade so the publication is, in no sense, a "Buy"; it is simply an indication that prices have gotten low enough that the list has more than 10 companies on it. (A month ago it had 5.)

Feb

3

Inflation and it’s Causes, from Asindu Drileba

February 3, 2025 | Leave a Comment

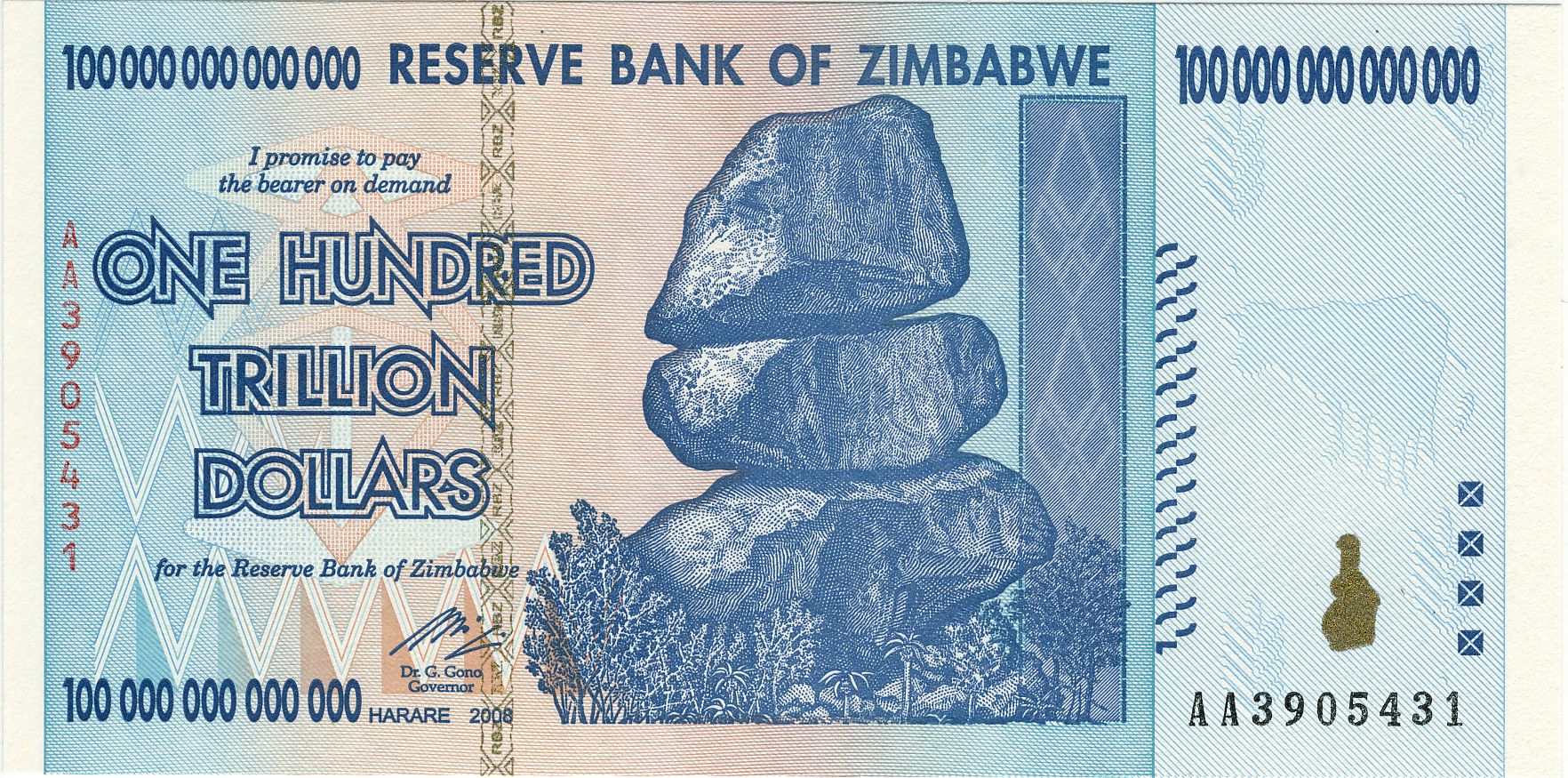

What causes inflation? Suppose we define inflation simply as the rise in prices of commodities, stocks, real estate etc. What causes it?

1) A generic explanation people offer (acolytes of Milton Friedman & Margaret Thatcher for example) is to blame monetary policy. Simplified as, inflation is caused by "too much money chasing too few goods."

Many people blamed President Trump's COVID stimulus packages for the rise of prices during that period. It seems specs in this list agree upon this when it comes to stock prices, i.e., lower interest rates (higher money supply) -> Higher stock prices (inflated stock prices).

2) An alternative explanation is that higher prices are caused by supply chain issues.

So they would claim that higher commodity prices were so because it was extremely difficult to move them around during lockdowns, let alone processing them in factories. A member also described that egg prices may be going up because of disease (a chink in the supply chain) not necessarily monetary policy. I am thinking that supply chain issues are more important to look at, than monetary policy.

Larry Williams predicts:

Inflation is very, very cyclical so maybe the real cause resides in the human condition and emotions. It will continue to edge lower until 2026.

Yelena Sennett asks:

Larry, can you please elaborate? Do you mean that when people are optimistic about the future, they spend more, demand increases, and prices go up? And then the reverse happens when they’re pessimistic?

Larry Williams responds:

Just that it is very cyclical— as to what drives the cycles I am not wise enough to know…though I suspect…some emotional pattern dwells in the heart and souls of as all that creates human activity—along the lines of Edgar Lawrence Smiths work.

Dec

29

Chance, luck, and ignorance: how to put our uncertainty into numbers

December 29, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Chance, luck, and ignorance: how to put our uncertainty into numbers - David Spiegelhalter, Oxford Mathematics

We all have to live with uncertainty. We attribute good and bad events as ‘due to chance’, label people as ‘lucky’, and (sometimes) admit our ignorance. In this Oxford Mathematics Public Lecture David shows how to use the theory of probability to take apart all these ideas, and demonstrate how you can put numbers on your ignorance, and then measure how good those numbers are.

Coffee cup he got from MI5 showing verbal-numerical scale they use.

Also: The Art of Statistics

William Huggins offers:

i like to give this guide to my students for whom English is a 2nd/3rd (sometimes 4th+ language).

Kim Zussman is unimpressed:

David Spiegelhalter was Cambridge University's first Winton Professor of the Public Understanding of Risk.

Translation: He is the most qualified of the vast array of those who don't know WTF they are talking about, but are knighted to tell us.

Peter Grieve responds:

I heard a story a decade ago about one of the big decision theorists, I think it was a Harvard professor. He was offered a position somewhere else, and was agonizing about whether to accept it. A colleague suggested he use his decision theory, and he said "Come on! This is serious!" I've no idea about the veracity of the story, or who was involved.

Alex Castaldo clarifies:

You are talking about Howard Raiffa. The story was told by another professor, although apparently Raiffa later denied that he had said it.

Nov

14

Crypto and the money supply, from Bill Rafter

November 14, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Should the market cap of crypto currencies be included in money supply for macroeconomic purposes?

William Huggins replies:

I'd you cant use it to pay taxes it doesn't count (just another asset, like a stamp).

Kim Zussman asks:

Why not? They add because if you pay taxes with fiat you can buy merch with crypto.

William Huggins responds:

you can barter wine or chocolate for a ton of things online too but we don't count those either. if money is "anything taken as payment" then we have to get very serious about "degrees of moneyness" (hence m0,m1,etc). in that spectrum, its pretty clear that the only things on the list are legal tender so unless you live in the land of bukele, it doesn't count (also, whose money supply does crypto count as exactly?)

Peter Penha:

I will volunteer that there is no moneyness to crypto as it was determined a 100% haircut asset by the DTC.

I think this leaves Blackrock and other crypto ETF managers in the interesting position that they cannot include crypto ETFs in one of their asset allocation funds or a target date fund, etc - inclusion would pollute.

Crypto in the USA appears to be a walled garden - the only contagion I can see to the financial world would be to holders of Micro Strategy Convertible Debt.

Stefan Jovanovich writes:

The question you all are raising here has a history - how far can "the law" go to monetize promises to pay? Originally, the answer was not one step. The Constitution says that legal tender can only be Coin. Article I, Section 8.

The lawyers have been working around that limitation ever since. Their greatest difficulty has been getting around the literalist non-lawyer Presidents who keep following the actual instructions the People established by vote as "the law".

Success came with the Aldrich-Vreeland Act which authorized banks with Federal charters to form "currency associations". Those were given authority to issue emergency currency could be backed by securities other than U.S. bonds, including commercial paper, state and local bonds, and other miscellaneous securities.

Section 18 of the Act: "The Secretary of the Treasury may, in his discretion, extend from time to time the benefits of this Act to all qualified State banks and trust companies, which have joined the Federal reserve system, or which may contract to join within fifteen days after the passage of this Act: Provided, That such State banks and trust companies shall be subject to the same regulations and restrictions as are national banks under this Act: And provided further, That the circulating notes issued under this Act shall be lawful money and a legal tender in payment of all debts, public and private, within the United States."

Everything since 1908 has been a variation on that theme - "lawful money" can be whatever Congress says it is.

Bill Rafter comments:

I started this question because I am working on a slight variation of digitally quantifying inflation. With the loose definition of inflation being “too much money chasing too few goods”, then the “money” part should include all that can conceivably buy the “goods”. Since one can increasingly buy a whole lot of stuff with crypto, then crypto deserves inclusion. If one were to fast-forward to a time of massive currency instability (this is just a thought experiment), having included the cryptocurrency might have facilitated greater forecasting.

Stefan Jovanovich adds:

For me the paradox of Bitcoin is that it has been a spectacularly successful asset - like a share of Berkshire Hathaway stock bought in the days before Buffett even went public - but it has never been a money. If I had Bill's brain and cleverness, I would try to include in the calculations the sum of personal and corporate credit that the lenders cannot easily pull away from the table (the potential moneyness supply) and the amount of credit actually used; and then seek the correlations to the fluctuations in that spread. In the days before central banking, speculators watched the net supply of commercial paper as such an indicator.

Sep

2

Counting: Seasonality

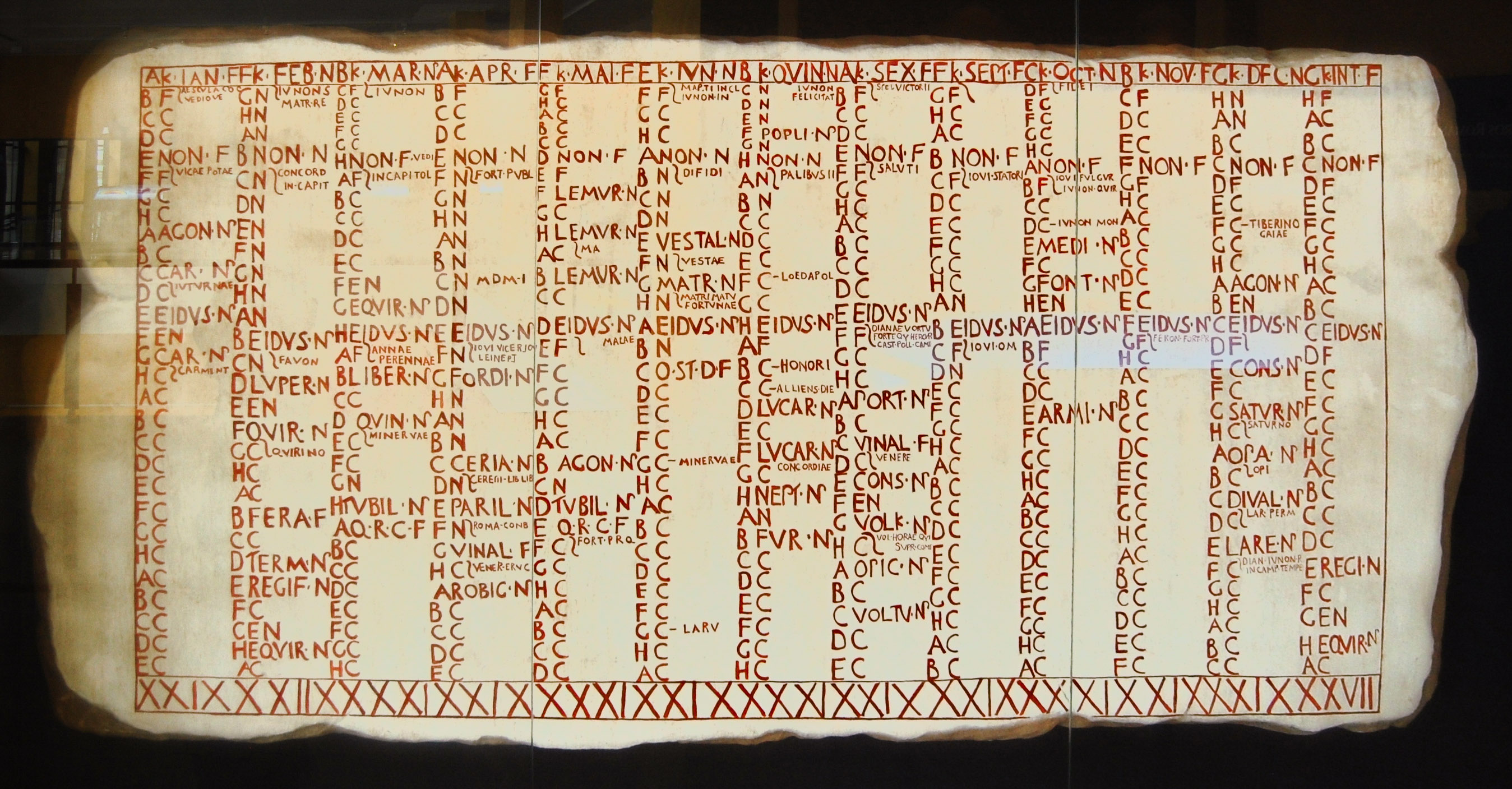

September 2, 2024 | 1 Comment

A lesson from the archives: Seasonality and changing cycles, by Victor Niederhoffer and Laurel Kenner, (04/26/2004)

A good part of the anomaly literature is devoted to studies of seasonality. A basic problem with these studies is that merely picking a season to study involves making guesses as to when and where the seasonality is. For example, is it in January or December, on Monday or Friday, in the United States or the Ukraine? (Yes, our Google search turned up a study of anomalies in the Ukraine.) Thus, the very choice of a subject might involve random luck.

Another aspect of seasonality studies that must be considered is whether the effects noted are sufficient to cover transaction costs. A retrospective study showing that you can make 2 cents more on Friday trades than Monday trades in your typical $50 stock would not be sufficient in practice to leave anyone but the broker and the market-maker richer.

Thus, it's essential to temper the conclusions of such studies with out-of-sample testing — in other words, with real trading.

[ … ]

Comment by Philip J. McDonnell, a former student of the Chairman at UC Berkeley: Dr. Niederhoffer points out that there is no a priori reason to believe that any one day of the week is stronger than any other. Thus when Y— collected the data (thank you!), presumably the reason was to find out if any days of the week behaved differently. Only after peeking at the data was it possible to say that Monday was the best and Tuesday the worst.

There are 10 such pairwise comparisons:

Mon with other 4 days 4

Tues with 3 last days 3

Wed with Thu & Fri 2

Thu with Fri 1

Total 10

In other words it is also possible that Tuesday could have been the best day and Monday the worst or any other pairwise comparison by chance alone. So when the one best and the one worst day shown by the data are compared and shown to have say a 5% significance we need to remember that we implicitly ruled out the other nine cases which weren't the best or worst. So we need to take our 5% number and multiply by 10 to get the correct significance of 50%. 50% is exactly consistent with randomness.

The problem is multiple comparisons are often subtle and remain unrecognized. Multiple comparisons are insidious because they dramatically reduce the power of the statistical tests we employ.

[ … ]

[More reading: Multiple comparisons problem]

William Huggins offers:

Bonferonni method suggests raising the confidence level proportional to the number of tested hypotheses. To get 95% confidence despite ten tests, he suggests 99.5 as a threshold. It's a huge problem when testing which variables to include in a regression model.

Asindu Drileba writes:

The right way to do this type of thing is to form a specific hypothesis based on a single comparison and then to test it on the data. It is even possible to use data from a prior period to formulate our hypothesis. We then test our hypothesis on the subsequent period which excludes the period where we formed our hypothesis.

This is an approach used in machine learning. Datasets are always split into "training" and "test" datasets. "Training" datasets are exclusively used to build the components of the model. "Test" datasets are not used to build the model at all. They are excluded when building the model. The model built using the "training" dataset is then asked to make predictions on the "test" dataset. The accuracy on predictions made on the "test" datasets is then used to determine how accurate the model is (so it can be tuned for improvement or thrown away).

I found this particular statement from the full post so insightful because I didn't think of applying this approach to building models using other statistical methods (I thought it was something limited to machine learning).

Aug

25

Counting and ML, from Paolo Pezzutti

August 25, 2024 | Leave a Comment

What is the role of Machine Learning models and Features selection in this "counting" philosphy? Have all these "new" methodologies overcome and made useless the traditional counting and statistical approach? Or can they coexist, as long as one can find a niche in which to conduct profitable operation?

William Huggins responds:

ML and feature selection run on "traditional statistics", which is basically about comparing empirical data to what randomness around a benchmark should look like. think of them as like hydraulics, which transformed the shovel into the backhoe for large operations but without rendering the "basic version" obsolete.

Big Al links:

In the Google Crash Course in Machine Learning, the first model is Linear Regression.

Aug

24

Meaning of “Counting”, from Asindu Drileba

August 24, 2024 | Leave a Comment

I remember an interview by Vic where he said he did a lot of "counting". Does he mean combinatorics? Or something else. What are some resources where he has talked about this "counting" in more detail?

William Huggins replies:

he literally meant count the data/do the math. at its most basic, statistics is about counting and comparing to the results we would have expected from randomness. too many people form their beliefs because they were told something, or were presented with cherry-picked "supporting" data so the chair's injunction has been to actually check before committing capital.

Zubin Al Genubi adds:

Count the number of: Private Jets, pretty girls, closed businesses, for lease signs, big market drops, increase in vix, number of down days, number of days since last high/low, volume of trades, bids, offers, crashes, all time highs, stocks at new highs/ lows, crosses of round numbers, cigarette butt length, change in price, etc etc.

Test: is number above or below mean/ median? How many standard deviations away from mean? What happened after the time of count?

Penny Brown adds more:

I'll add to the list: the price of thoroughbred horses sold at auction and the length of women's dresses. (long hem below knee is bearish as was style in 70s, short hem in mini skirts is bullish)

Asindu Drileba responds:

Thank you. "Test Everything" is definitely something that keeps coming up whenever I listen to the chair.

Humbert H. asks:

In all these years I could never understand how this approach can coexist with affirming the reality of the ever-changing cycles. Like how do you know when to trust this counting and when the cycles changed on you?

Laurence Glazier offers:

Music is the pleasure the human mind experiences from counting without being aware that it is counting.

- Gottfried Leibniz

Aug

23

Counting is one thing, statistics is another, from Carder Dimitroff

August 23, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Today, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) is counting how many power plants were added in the first half of 2024 and projecting how many will be added in the last half.

It's all wonderful news. About 20.2 GW (the equivalent of about 18 nuclear power plants) were added. By the end of the year, EIA expects about 62 GW of new capacity. About 95 percent of these additions are intermittent sources (wind, solar, batteries).

Offsetting this new capacity are retirements. Utilities plan to retire 7.6 GW, all of which use coal, natural gas, and petroleum as fuel. They are likely being retired because they are uneconomic and rarely dispatched. Their levelized costs exceed revenues, and investors want to tidy up their books.

Statistics unearth a problem that counting hides. The problem is not on the supply side; it's on the demand side. Specifically, counting 24/7 demand reveals tremendous growth (e.g., baseload). It appears there's a hidden mismatch between supply and demand. While there will be hours on most days when the grid is flooded with cheap power, there will also be hours on other days when there will not be enough supply to serve all loads.

Retail prices will jump. In fact, they already have. PJM is the Regional Transmission Organization (RTO) that manages bulk power markets for the mid-Atlantic region. It's one of the largest of the nation's ten RTOs. In addition to transmission line responsibilities, PJM manages energy and capacity auctions for power plant production.

PJM conducts an auction for capacity each year. Power plant asset owners may enter the auction and offer their prices. Owners are paid a daily rate for each megawatt if their bids clear. Auction results:

2024/2025

$28.92 / MW-day

2025/2026

$269.92 / MW-day

Next year, a 1,000 MW power plant can earn $269,920 daily compared to $28,920 this year. These payments are in addition to any revenues earned from energy auctions.

While these auctions seem arcane to the average consumer, they will feel it in their pocketbooks—and not just in one part of the country—it's everywhere. All these costs will flow to the consumer, who will have only the choice of paying or reducing consumption.

Two options may become quickly viable. One is to build gas turbines as fast as possible. To attract investors, capacity payments have to be attractive. But starting new projects today may be too late.

The other option is "demand-response," where consumers are enticed to reduce demand for a price. Demand response is in place today but has yet to be aggressively implemented. It appears grid operators like PJM (not the government) will be forced to become aggressive and offer lucrative demand-response programs.

Lastly, those who invest in "behind-the-meter" assets like their own renewable energy sources, including geothermal, will avoid some of these accelerating costs. Those who have already invested will likely experience returns higher than expected.

The roots of this problem germinated decades ago. That is its own story for another time.

Kim Zussman wonders:

XLU?

Big Al observes:

XLU up 25% from Feb low.

Jeffrey Hirsch was there before us:

Our recommendation at the outset of XLU/Utes seasonal bullish March-Oct period.

Humbert H. writes:

Nuclear is clearly the real solution as the current generation of nuclear reactors are pretty much (we hope) not vulnerable to meltdowns. But as the situation stands, battery technology is likely to receive an ever-increasing amount of investment, and also reused old EV batteries will be more and more prevalent as storage banks for solar and wind. Intermittent sources = more and more need for battery capacity.

William Huggins offers:

one possible solution to transmission problems is to use rail-bound batteries.

Aug

22

Talks on financial history, from William Huggins

August 22, 2024 | Leave a Comment

A great thanks to Henry for sharing his book Buildings Don't Lie. As a prospective homeowner, I plan to devour it upon arrival.

I don't have a proper book to share but I did author a course on financial history that I teach. To help my students, I recorded all the one-directional talks as short videos. Rather than proceeding chronologically overall, I broke things down into 11 topics (plus an intro) and did those chronologically: payments, debt, banking, central banking, companies, stock markets, derivatives, insurance, trusts and funds, pensions, government finances.

Jul

28

Inflection points, from Zubin Al Genubi

July 28, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Inflection points at prior highs and lows seem pretty obvious recently especially in lowered liquidity. The market makers seem to thin and spread their markets for protection resulting in bigger directional moves. The vol gives a small trader good opportunity as the big boys dump large orders creating large auto trade moves like escalators.

Anatoly Veltman wants more information:

every word I read on three lines of text appears totally (?) random. It would be extremely impressive, if you ventured to explain at least ONE of these, and how this could be used as edge. P.S. Bonus would be to know the approximate date (?) of "lowered liquidity"

William Huggins responds:

It's not random, it's about microstructure. MMs spread their risk as they usually get caught out by information driven moves while they supply liquidity. When they spread their capital to diversify, or withdraw from choppy markets, the price impact of trading rises (Kyle's lambda).

Steve Ellison comments:

My takeaway from Zubin's post is that there are edges to be found in studying market microstructure and looking for clues in price action of what some of the key players are doing. A specific example I have found is, if you bin trading days by number of days before or after options expiration, options expiration day has had the worst total return in the S&P 500 of any day of the month in the past 6 years or so. Apparently the need for a large number of market players to adjust and re-establish hedges can create imbalances in supply and demand of various assets.

I could form a hypothesis about liquidity that a sustained price move in one direction, as happened a couple of times to the downside in the S&P 500 since July 17, is toxic for market makers and forces them to widen their spreads lest they be saddled with unwanted inventory. I'll leave it as an exercise for the reader to test this hypothesis.

Jul

19

The golden ratio

July 19, 2024 | Leave a Comment

golden ratio of 1.65 appears in thousands of settings over thousands of years.

The Golden Ratio: The Divine Beauty of Mathematics, by Gary B. Meisner (Author) and Rafael Araujo (Artist)

The Golden Ratio examines the presence of this divine number in art and architecture throughout history, as well as its ubiquity among plants, animals, and even the cosmos. This gorgeous book—with layflat dimensions that closely approximate the golden ratio—features clear, enlightening, and entertaining commentary alongside stunning full-color illustrations by Venezuelan artist and architect Rafael Araujo.

A trader writes:

I have used the golden ratio trying to predict where the technical people find Fibonacci support and resistance levels in both cash and futures and applying them to grain spreads and basis capture. This was in conjunction with other tools being used and tested. I completely abandoned the method after finding other, more successful ways that work better than random.

William Huggins offers an historical lagniappe:

Leonardo of Pisa may be best known for his "sequence" but in his lifetime, it was his work as a tutor to the rich business class of late-Medieval Italy that paid the bills. His mathematical treatise Liber Abaci (1202), which was only "recently" translated into English, is broken into chapters including basic operations but he quickly jumps into the calculation of profits from business voyages and even introduces the notion of the time value of money.

Jun

15

Megacaps in Random Land, from Big Al

June 15, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Lots going around about how NVDA dominates; and MSFT, NVDA and AAPL now account for about 20% of the S&P 500. I was curious to see what happened in a toy index and so did an experiment (using R):

1. Create an index of 500 stocks, each with a starting value of $100.

2. Each year, for 40 years, each stock's value is multiplied by 1 + a value randomly drawn from a normal distribution with mean 8% and sd 15%, roughly what you might see with the S&P 500.

3. The starting value of the index was $50,000. The final value after 40 years was $1,152,446.

4. The final summed value of the largest 10 out of 500 stocks was $142,320, or 12.35% of the 500-stock index.

I was curious to see if megacaps would emerge from a simple toy model. I ran it only once, and they did. For me, this is a comment on the perennial alarm stories about "Only X% of stocks account for Y% of the market!" Even with a simple model, you wind up with something like that.

Adam Grimes agrees:

Can confirm. Have done variations of this test with more sophisticated rules, distribution assumptions, index rebalancing, etc. Get similar results.

Peter Ringel responds:

so we can take this ~12% of the index as a base value, that develops naturally or by chance? Then a clustering of being 20% of a total index (only greater by 8%) does not look so outrageous.

William Huggins is more concerned:

keep in mind it's 10 companies making up 12% (~1.2% each) vs 3 companies making up 20% (8.3% each) - in that sense, the concentration DOES look pretty high. am reminded of when NT was 1/5 of the entire CDN index in 99/00.

Peter Ringel replies:

You are right, I failed to catch this difference of only 3 stocks. In general, I am not so much surprised about the concentration. Money always clusters. Always clusters into the perceived winners of the day. Should they blow up, money flows into the next winner. To me, the base for this is herd mentality.

Adam Grimes comments:

It's Pareto principle at work imo. I'm not making any claims about exact numbers or percents, but as you use more realistic distribution assumptions (e.g., mixture of normals) the clustering becomes more severe. There's nothing in the real data that is a radical departure from what you can tease out of some random walk examples. Winners keep on winning. Wealth concentrates. (As Peter correctly points out.)

Asindu Drileba offers:

Maybe you try replacing the normal distribution of multiples with a distribution of multiples constructed with those historically present in the S&P 500? It may reflect the extreme dominance in the market today.

To me, the base for this is herd mentality.

It is also referred to as preferential attachment:

A preferential attachment process is any of a class of processes in which some quantity, typically some form of wealth or credit, is distributed among a number of individuals or objects according to how much they already have, so that those who are already wealthy receive more than those who are not. "Preferential attachment" is only the most recent of many names that have been given to such processes. They are also referred to under the names Yule process, cumulative advantage, the rich get richer, and the Matthew effect. They are also related to Gibrat's law. The principal reason for scientific interest in preferential attachment is that it can, under suitable circumstances, generate power law distributions.

Zubin Al Genubi writes:

Compounding of winners is also at work and returns will geometrically outdistance other stocks. No magic, just martini glass math.

Anna Korenina asks:

So what are the practical implications of this? Buy or sell them? Anybody in the list still owns nvda here? If you don’t sell it now, when?

Zubin Al Genubi replies:

Agree about indexing. Hold the winners, like Buffet, Amazon, Microsoft, NVDIA. Or hold the index. Compounding takes time. Holding avoids cap gains tax which really drags compounding. (per Rocky) Do I? No, but should. It also works on geometric returns. Avoid big losses.

Humbert H. wonders:

But what about the Nifty Fifty?

Apr

25

FTC Announces Rule Banning Noncompetes, from Big Al

April 25, 2024 | Leave a Comment

FTC Announces Rule Banning Noncompetes

Today, the Federal Trade Commission issued a final rule to promote competition by banning noncompetes nationwide, protecting the fundamental freedom of workers to change jobs, increasing innovation, and fostering new business formation.

“Noncompete clauses keep wages low, suppress new ideas, and rob the American economy of dynamism, including from the more than 8,500 new startups that would be created a year once noncompetes are banned,” said FTC Chair Lina M. Khan. “The FTC’s final rule to ban noncompetes will ensure Americans have the freedom to pursue a new job, start a new business, or bring a new idea to market.”

Kim Zussman writes:

This will also help knock down the value of businesses. Mike sells his business to Mary. One week later Mike opens the same kind of business one block away, and contacts all his old customers. How much should Mary pay to buy Mike's business?

H. Humbert comments:

Certainly has more merit than trying to destroy Amazon or preventing Kroger from buying Alberson's, her two other favorite busybody activities. Not a very libertarian thing to do, but noncompetes are often used against many powerless people as a nakedly aggressive move.

The argument she uses is that Silicon Valley where noncompetes are illegal beat out Boston Route 128, and is doing just fine in terms of starting new businesses. Whether it's due to noncompetes or the weather is anybody's guess. The other argument is that noncompetes are used to restrain security guards or sandwich shop workers from getting employment across the street, cases where intellectual property or customer lists are clearly not involved.

Pamela Van Giessen adds:

There is another downside to this. When companies lay off people, especially middle and senior management, they give them attractive parting gifts that are contingent on non-compete agreements. E.g, ABC co lays off senior manager, pays them up to 1 yr salary plus health benefits, etc. but the caveat is that former senior manager doesn’t work for a competitor for x period of time. These workers already have the right to decline the parting gifts if they don’t want to sign the non-compete. Now there is almost no incentive for companies to provide compensation to the people they lay off since they can’t bargain for a non compete. That sucks for employees who can now be laid off with pretty much nothing. I’d say this is a loss for employees and a win for big companies. Thank you to Joe Biden & co.

William Huggins responds:

let's not oversell this - firms seek out non-compete agreements for THEIR benefit, not that of employees. strange that an erosion of their position would somehow strengthen them but war is peace and ignorance strength?

Apr

23

Speak of the devil, from William Huggins

April 23, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Looks like someone in Can Gov was listening in for ideas (Tax rate to rise from 50% of reg to 67% of reg):

In the 2024 budget unveiled Tuesday, Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland said the government would increase the inclusion rate of the capital gains tax from 50 per cent to 67 per cent for businesses and trusts, generating an estimated $19 billion in new revenue. Capital gains are the profits that individuals or businesses make from selling an asset — like a stock or a second home. Individuals are subject to the new changes on any profits over $250,000.

Big Al is sanguine:

No worries - it only affects a few:

The government estimates that the changes would impact 40,000 individuals (or 0.13 per cent of Canadians in any given year)…

H. Humbert writes:

With 67%, the government clearly thinks that either it both needs and deserves the profits of some people more than they do OR that those people need to be treated like one would treat an enemy, without any regard for their needs or feelings. Let's see, would a Communist think that way (both ideas) about his or her class enemy?

William Huggins explains:

It's a move back towards the status quo ante 1980s tax cut. The idea that tax cuts are only good is just silly. As silly as the notion that government is efficient with those same taxes. This isn't revolutionary, simply the slow reduction of a subsidy we -thought- would lead to more investment. Turns out future demand is a larger determinant of that than current taxes. We gave too much to capital back in the early 80s when we rebalance last time and now were rebalancing again. Cap gains will still pay less tax than working folks. No need for enemies or "communists".

H. Humbert replies:

I apologize William, the problem was my reading comprehension as I wasn't familiar with the meaning of the term "inclusion rate" in the Canadian tax system and interpreted it incorrectly after, to be honest, spending about 20 seconds to "read" the article. With your explanation and the tiniest bit of research, this makes sense. As I mentioned before, I'm against special cap gains rates, but only if (a) the losses aren't capped (b) there is no special "investment gains" tax as currently exists in the US.

Asindu Drileba adds:

David Graeber once mentioned that the most productive period in American industry was when the tax rates were highest (65%). The referenced the advances made by Bell Labs as a example. He claimed that the productivity occurred because corporations were nudged by the high taxes to invest more money into research and development.

H. Humbert provides context:

Very few people paid the top marginal rate as tax shelters were highly prevalent and a lot easier to use than they are now.

Hernan Avella comments:

True MMT’rs would argue that rates should be 0 and the tax rate higher, as needed to curb inflation.

Apr

16

Higher for longer, from Nils Poertner

April 16, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Investors wrongfooted as ‘higher for longer’ rates return to haunt markets

Zubin Al Genubi asks:

Interest alone on US debt is 1 trillion dollars a year! Anyone concerned?

Larry Williams is definite:

NOPE. NOT AT ALL.

Art Cooper, however:

*I* am certainly concerned, in the long term. When the coverage ratio on gov't debt auctions drops close to 1.0, it will be time to take meaningful action, with a major re-allocation of investment portfolios.

Larry Williams responds:

Not to worry…says MMT guys…as long as we are not gold-backed $, it's all just accounting numbers.

Kim Zussman wonders:

Reallocate to what? (he says looking around twice with stocks near ATHs)

Art Cooper suggests:

There are a universe of hard assets out there, including gold (though GLD could easily go far higher). Because I like to emulate the Sage and shop in the bargain basement, I personally find extremely distressed income-producing real estate of interest. Babies are being thrown out with the bath water.

Larry Williams writes:

The public debt is just $ in savings accounts at the Federal Reserve Bank. When it matures the Fed transfers those dollars to checking accounts (aka reserves) at the same Fed. It's just a debit of securities accounts and a credit of reserve accounts. All internal at the Fed. When gov sells new Tsy secs, the Fed debits the reserve accounts and credits securities accounts. Those $ only exist as balances in one account or the other.

Asindu Drileba adds:

David Graeber once mentioned that the US can never default on its debts since the Fed is the largest holder of Treasuries.

William Huggins comments:

its not that the US -can't- default on its debts, its that 70% of those debts are to americans. so what is the probability of americans voting to default on themselves when they have the ready alternative of printing money? more important might be whether or not the 30% foreign holders will keep playing along but that analysis is an exercise in ranking "next best alternative" for them. when one starts looking under the hood at the alternatives, its boils out like china's bank regulator said in early 2009, "except for treasuries, what can you hold? gold? you don't hold japanese government bonds or uk bonds. us treasuries are the safe-haven. for everyone, including china, it is the only option: "we hate you guys but there is nothing much we can do."

H. Humbert replies:

The Americans would be about equally unlikely to default if most of the debt was held by foreigners. If you can print money there is no need to piss off any of your "customers". It's not like things worked out super well for Argentina, at least until they hit bottom.

Apr

15

Reading (and viewing) recommendations

April 15, 2024 | Leave a Comment

From Easan Katir:

The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays, by Simon Leys.

Simon Leys is a Renaissance man for the era of globalization. A distinguished scholar of classical Chinese art and literature and one of the first Westerners to recognize the appalling toll of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, Leys also writes with unfailing intelligence, seriousness, and bite about European art, literature, history, and politics and is an unflinching observer of the way we live now.

From Zubin Al Genubi:

Pathogenesis: History of the World in Eight Plagues, by Jonathan Kennedy.

According to the accepted narrative of progress, humans have thrived thanks to their brains and brawn, collectively bending the arc of history. But in this revelatory book, Professor Jonathan Kennedy argues that the myth of human exceptionalism overstates the role that we play in social and political change. Instead, it is the humble microbe that wins wars and topples empires.

From Asindu Drileba:

Math Without Numbers, by Milo Beckman.

Math Without Numbers is a vivid, conversational, and wholly original guide to the three main branches of abstract math—topology, analysis, and algebra—which turn out to be surprisingly easy to grasp. This book upends the conventional approach to math, inviting you to think creatively about shape and dimension, the infinite and infinitesimal, symmetries, proofs, and how these concepts all fit together. What awaits readers is a freewheeling tour of the inimitable joys and unsolved mysteries of this curiously powerful subject.

Peter Ringel is watching:

Voltaire: The Rascal Philosopher

I discovered a terrible knowledge gap and missed details of a great one. so many angles to be impressed. his writings seem to be the least of it. he even gamed the king's lottery and won with a group of investors & mathematicians.

William Huggins suggests a somewhat older work:

A General History of The Most Prominent Banks, by Thomas H. Goddard, published in 1831.

its dry - but if you are interested in the 1819 panic, there are some good details. the book is mistitled imo as 3/4 of its pages and 2/3 of its text centers on the history of central/national banking in the united states from 1786 through 1831 (publication). on titular matters, it had a couple of interesting tidbits on the bank of genoa and some "interesting" statistical information for archivists but there are better modern sources on major banks in venice, the netherlands, england, and france (for example, the author skips over how the bankers of geneva funded the french revolution to knock the bank of genoa off its perch, etc). i suspect such deficiencies are because the text was designed as ammo in the "bank wars" of the early 1830s rather than a deep exposition on titular topics.

its exposition on us matters feels remarkably haphazard, i presume because the author's intended audience would have the context to appreciate why it includes what it does, including a description of the bank of north america, hamilton's report to congress on the need for a bank, and a brief on the First Bank of the US. where it begins to shine is in the next set of docs, which includes an auditor's report and statement by the president of the Second Bank of the US on how the panic of 1819 was navigated. it follows with mcduffie's 1930 report to congress on the SBUS (includes more details on the rise and fall of FBUS), and closes with a statistical archive of the "monied institutions of the US" and an appendix on how banking and commercial exchange granularly worked in the 1800s.

Stefan Jovanovich comments:

I was puzzled by the "decline and fall" description, since the Bank did not fail but simply had its charter expire without renewal because George Clinton did not like what Thomas Willing had done as President of the Bank. (Clinton failed to cast what would have been the winning vote for renewal.)

William Huggins responds:

"fall" referring to its near brush with survival, not any sort of mismanagement or fraud as in 1819. mcduffie describes FBUS as the victim of partisan politics, but one of such import that the same party who killed it started calling for a replacement almost immediately.

Stefan Jovanovich adds:

They wanted what Willing would not give them - a central bank that would do what the Fed does now - discount the Treasury's IOUs at par. Can't have a war without that.

Mar

29

Weekend reading

March 29, 2024 | Leave a Comment

Recent list recommendations:

From Zubin Al Genubi:

The New Money Management: A Framework for Asset Allocation, by Ralph Vince.

The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, by Gustave Le Bon.

The Crowd. Must read. In crowds individual lose their intelligence, morals, and judgement and a new entity acts without credulity, irritably, and subject to whims, heroism and depravity.

1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed

William Huggins adds:

I enjoyed 1177 BC a few years back as it gave a general overview of the geopolitical state of play towards the end of the Bronze Age. It summarized most of the theories underpinning the "bronze age collapse" which occurred around that time and left less than half the "civilized" world in the state it had been a century before. Doesn't offer much in terms of new evidence but it a decent quick read.

From Nils Poertner:

Tech Stress: How Technology is Hijacking Our Lives, Strategies for Coping, and Pragmatic Ergonomics