Feb

18

Vol in percent versus dollars, from Zubin Al Genubi

February 18, 2026 |

More on the points vs % argument. % vol or Vix is misleading and inaccurate measurement of vol. A better measure is abs vol in points/$ because we live and measure ultimately in dollars.

Accordingly at 7000 abs vol is 350% of what is was a few years ago at 2000. Trading has to adjust accordingly to maintain the same portfolio volatility of returns. Thus leverage, targets, systems, time have to adjust to match.

Adam Grimes disagrees:

because we live and measure ultimately in dollars

This does not strike me as coherent. Returns are the only reasonable way to understand market movements. Just imagine a portfolio of two assets, one at $1 and the other at $100,000 (or other arbitrarily wide handles). The only way to think about those is to normalize for price via %, so it follows that volatility would be equally incoherent measured in points. (Sorry for the Finance 001 example, but I think 'Explain It Like I'm Five Years Old' cuts through a lot of confusion.)

% and vol measured as vol of %'s (i.e., returns) is the only thing that makes actual sense here unless I'm misunderstanding the argument. What am I missing?

Accordingly at 7000 abs vol is 350% of what is was a few years ago at 2000.

Scratching my head here. "So what?" and "of course" are the only things I could manage to say here.

I'm probably missing something, though. What is it? (btw VIX sucks as much as any other clunky measurement of implied vol. I'll agree with you on that one, but I don't think that's your point.)

Zubin Al Genubi responds:

1 ES contract used to move 7 points as an average range 20 years ago. You made or lost $350. 1 contract now moves 50 or 100 points a day, same percentage, but your account is up or down $5000. The volatility in your account in dollars is higher than 20 years ago. If you lost 1% in 2000, its $600, but 1% now is $3500 per contact. You don't see too many 2% days like before. Abs vol is up while Vix or % vol is down. Its apples and oranges.

The trading style, research should change. Straight percentages for expectations, returns, targets don't work like they used to, especially using historical data. Silver now has micro contract because $5000 a dollar too is high volatility in dollars with $20 or more ranges. I guess I'm suggesting using abs vol as a better measure of vol.

Appropriate here, Feynman in 6 Not so easy pieces, cites Wyle on symmetry, "Suppose we build a certain piece of apparatus, and then build another apparatus five times bigger in every part, will it work exactly the same way? The answer is, in this case, no!" My point is the market does not the same way as it did 25 years ago in large part because it is bigger. The fact that the laws of physics are not unchanged under a change of scale was discovered by Galileo. He realized that the strengths of materials were not in exactly the right proportion to their sizes. [Ibid]

Adam Grimes writes:

I'm sorry, but I still find these points trivially obvious. Of course nominal price swings are bigger because price levels are higher, so of course holding a single contract would result in larger dollar swings. Who's holding a single contract? Position size takes care of all of this.

And I don't think the physical analogs add anything beyond confusion. Physical properties scale differently. For instance volume scales as cube and surface area as square. This is why we could not have a science fiction 100 ft tall lobster in reality…because of material constraints. There's no market analog to this. A 1% move is a 1% move. There's no hidden non linearity there.

If your claim is that markets don't move the same they did 25 years ago I would challenge that claim. What's the evidence for this? Statistically there's always the issue of non-stationarity but it seems to me you're claiming there's something more meaningful here. What am I missing?

Asindu Drileba comments:

I think Zubin is simply trying to say that he had found measuring volume in dollar terms (absolute terms) more relevant than measuring it in percentage terms.

Richard Hamming has an interesting talk, You get what you measure

Here us a good summary:

You may think that the title means if you measure accurately you will get an accurate measurement, and if not then not; it refers to a much more subtle thing - the way you choose to measure things controls to a large extent what happens. I repeat the story Eddington told about the fisherman who went fishing with a net. They examined the size of the fish they caught and concluded there was a minimum size to the fish in the sea. The instrument you use clearly affects what you see.

I for example, completely stopped measuring market returns in percentage terms a few years ago. I now exclusively use log returns. Why did I stop using percentages? The problem with percentages is that they are not equal to each other (ignoring the negative sign). (a 50% move) + ( a -50% move ) does not give you 0 in dollar terms. But what you get is 0% in percentage terms. Percentages are not symmetrical. Does this mean they don't measure growth? They actually do. But they simply should not be compared. As the absolute values may mean something different.

- A 0% return percentage may (erroneously)

indicate that you have broken even.

- The same 0% percent return may also show that you are actually loosing money in absolute (dollar) terms

Adam Grimes writes:

Of course log returns are well known, and this is more finance 101. There are several qualities that make them more attractive for some analyses. (just dont mix percents and log returns!)

But that's not the same as measuring market movements in raw dollars (which is the only reasonable companion to volatility measured in absolute dollars (or points).

And as for measuring what you see, methodology (and perhaps even experimenter expectations) greatly affecting outcomes and conclusions, we're on the same page there. This is fascinating territory for discussion and I'd welcome it.

But his point about volatility only extends to someone trading a single contract in 2001 and also trading a single contract today. That is irrelevant.

If there's something at work here and legitimately some way the market "doesn't move the same way" it did decades ago… I'm all ears and very interested. Always looking to learn more about what I don't know or might be missing.

Zubin Al Genubi does some counting:

There were 31 days in 2006 and 67 days in the last year with percent moves >1%. This is due to Big Tech being 32% of ES with higher beta and the speed and intraday persistence of algorithmic trading. Lastly, it 'feels' different. A 120 point drop trades different than a 13 point drop in 2002.

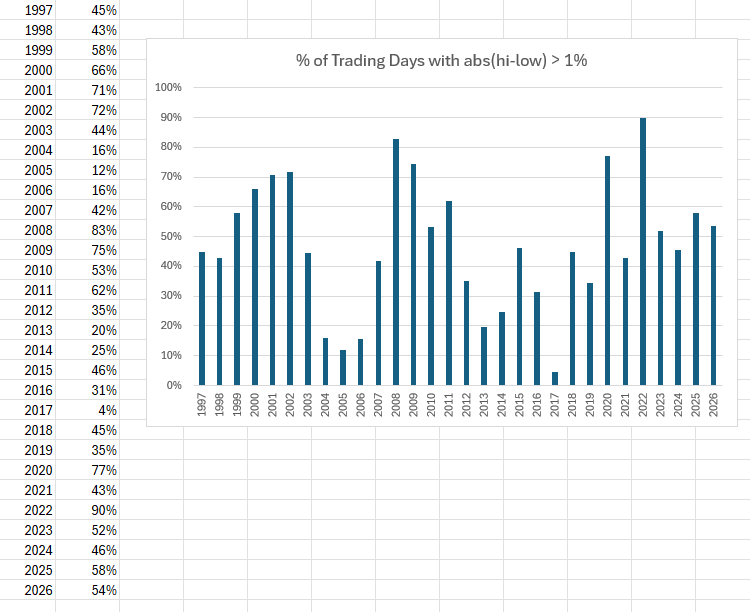

Stated quantitatively, now nearly half of our trading days have abs vol hi-lo >1% while in 2006 only a quarter of days had abs vol >1%. That is a big difference and clearly explains why trading is different (better) now. Today is just 1 of the many such days.

Cagdas Tuna adds:

All futures contracts of index products have adjusted to gross notional value of underlying stocks. At the same time VIX contract specifications and notional value it can represent almost remain unchanged. Although calculation method of VIX is the same, the number of futures contracts hedgers need to cover notional values they trade in underlying assets are totally different.

Adam Grimes writes:

Stated quantitatively, now nearly half of our trading days have abs vol hi-lo >1% while in 2006 only a quarter of days had abs vol >1%.

I'm sorry but I have to be direct. I find this annoying. You have moved the goalposts and are now making a completely different argument. You began advocating for measuring volatility in absolute dollars and now you are using a percentage measure. You are literally using the metric you said was wrong to support your argument that the metric is wrong.

Furthermore, your data are bad. It's simply a volatile measure. Volatility is volatile. Here's a look at the FULL history of the ES futures [first chart] (back-adjusted so this may not be fully accurate, but I think the % adjustment fixes the back-adjustment distortion) counting the number of trading days in each calendar year that had abs(high-low) / close > 1%. It's simply an unstable measure and I don't know what is to be drawn from this.

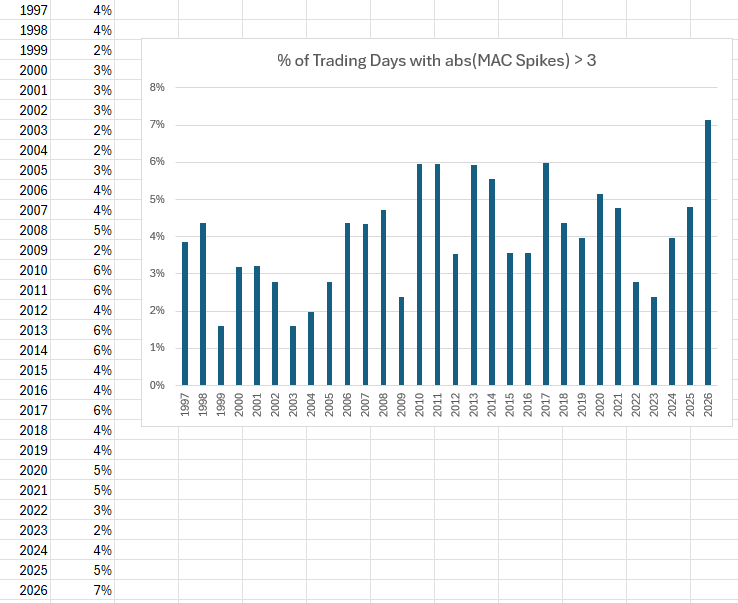

If your argument is that there are more days with "surprise" distortions, this is maybe nominally true, but better measured with better tools. I use a tool that expresses each day in terms of the mean average absolute closing difference [second chart]. Taking an arbitrary bound of 3 for that, the argument that this year is on track to show more surprise shocks than usual is true (but also reflective of a generally lower baseline).

You've flipped to percentage measures and we're left with hand waving "it feels different now." That's a different claim and it's qualitative, perhaps has value, but not in supporting your original claim.

I'll reiterate my position: percentage measures are the only thing that make sense. Point values are arbitrary and can be easily handled via position sizing (within the limits of granularity of instruments vs account size.) I don't think this is revolutionary or controversial. This is truly finance 101.

Comments

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- Older Archives

Resources & Links

- The Letters Prize

- Pre-2007 Victor Niederhoffer Posts

- Vic’s NYC Junto

- Reading List

- Programming in 60 Seconds

- The Objectivist Center

- Foundation for Economic Education

- Tigerchess

- Dick Sears' G.T. Index

- Pre-2007 Daily Speculations

- Laurel & Vics' Worldly Investor Articles