Feb

17

View for Skeptics, by Kim Zussman

February 17, 2007 | Leave a Comment

Finally (yeah right), "how low can it go?"

Using same SP500 series of 20 day standard deviations, only 57/719 (8%) periods had st dev <0.004 (0.4%) like the period before last (1/19/07=0.0038). In the past 57 years, what happened in the 20 day following those with st dev<0.004? The next period st dev mean was 0.0044, slightly higher.

But interestingly 25/57 (44%) were actually lower the next period. So it seems looking back that volatility has frequently gone lower from periods comparable to today, even before we were protected by world-dominating military and Ben Putnanke.

This and the trumpets blowing for the breakout/new highs/Dow theory crowd doesn't look good for us skeptics.

Feb

8

Negative Feedback and Trend Following, by Victor Niederhoffer

February 8, 2007 | Leave a Comment

There has been entirely too little thought given to the mechanism, pathways and reasons that negative feedback works in markets. Perhaps the main reason is that the feeding web is based on a reasonable stability in what and how much is being eaten and recycled.

There has been entirely too little thought given to the mechanism, pathways and reasons that negative feedback works in markets. Perhaps the main reason is that the feeding web is based on a reasonable stability in what and how much is being eaten and recycled.

The people who consume and redistribute must maintain a ready and stable supply of those who produce. They develop mechanisms to keep everything going. One of them is the specialization and great efficiency in their activities. If markets deviate too much from the areas and levels within which the specialization has developed, then much waste and new effort and mechanisms will be necessary.

Aside from the grind that trend following causes (i.e. the losses in execution), and the negative feedback system of movements in the supply and demand schedules that equilibrate, which Marshall pioneered and are now standard in economics, and the numerous other reasons I've set forth (e.g. the fixed nature of the system and the flexibility to profit from it), this appears to me to be the main reason that trend following doesn't work.

Here are a few interesting articles on the subject:

How Great Traders Make Millions in Up or Down Markets

Does Trend Following Work On Stocks?

Interviews At RealWorld Trading

Bill Rafter writes:

Dr. Bruno had posed the idea of beating an index by deleting the worst performers. This is an area in which we have done considerable work. Please note that we do not consider this trend-following. The assets are not charted, just ranked.

Let us imagine an investor who is savvy enough to identify what is strong about an economy and invest in sectors representative of those areas, while avoiding sectors representing the weaker areas of the economy. Note that we are not requiring our investor to be prescient. He does not need to see what will be strong tomorrow, just what is strong and weak now, measured by performance over a recent period.

What is a market sector? The S&P does that work for us, and breaks down the overall market (that is, the S&P 500) into 10 Sectors. They further break it down into 24 Industry Groups, and further still into 60-plus Industries and 140-plus Sub-Industries. The number of the various groups and their constituents changes from time to time as the economy evolves, but essentially the 500 stocks can be grouped in a variety of ways, depending on the degree of focus desired. Some of the groupings are so narrow that only one company represents that group.

Our investor starts out looking at the 10 Sectors and ranks them according to their performance (such as their quarterly rate of change). He then invests in those ranked first through fourth (25 percent in each), and maintains those holdings until the rankings change. How does he do? Not bad, it turns out.

www.mathinvestdecisions.com/Best_4_of_10.gif

From 1990 through 2006, which encompasses several types of market conditions, the overall market managed an 8 percent compound annual rate of return. Our savvy investor achieved 10.77%. A less savvy investor who had the bad fortune to pick the worst six groups would have earned 7.23%. Those results are below. (Note, for comparison purposes, all results excluded dividends.)

www.mathinvestdecisions.com/Worst_6_of_10.gif

How can our savvy investor do better? By simply sharpening one's focus, major improvements can be achieved. If instead of ranking the top 4 of10 Sectors, our savvy investor invests in a similar number (say the top 4, 5 or 6) of the 24 Industry Groups, he achieves a 13.12% compoundedannual rate of return over the same period. Note that the same stocks are represented in the 10 Sectors and the 24 Industry Groups. At no time did he have to be prescient.

www.mathinvestdecisions.com/Going_to_24_groups.gif

One thing you will notice from the graphs above is that the equity curves of our savvy and unlucky investors mimic the rises and declines of the market index itself. Being savvy makes money but it does not insulate one from overall bad markets because the Sectors and even the Industry Groups are not significantly diversified from the overall market.

Why not keep going further out and rank all stocks individually? That clearly results in superior returns, but the volume of trading is such that it can only be accomplished effectively in a fund structure - not by the individual. And even ranking thousands of stocks will not insulate an investor from an overall market decline, if he is only invested in equities. The answer of course is diversification.

It is possible to rank debt and alternative investment sectors alongside equities, in the hope of letting their performances dictate what the investor should own. However the debt and commodities markets have different volatilities than the equities markets. Anyone ranking them must make adjustments for their inherent differences. That is, when ranking really diverse assets, one must rank them on a risk-adjusted basis for it to be a true comparison. However if we make those adjustments and rank treasury bonds (debt) against our 24 Industry Groups (equity) we can avoid some of the overall equity declines. We refer to this as a Strategic Overlay:

www.mathinvestdecisions.com/Strategic_diversification.gif

Adding this Strategic Overlay increases the returns slightly, but more important, diversifies the investor away from some periods of total equity market decline. We are not talking of a policy of running for cover every time the equities markets stall. In the long run, the investor must be in equities.

Invariably in ranking diverse assets such as equities, debt and commodities, our investor will be faced with a decision that he should be completely out of equities. It is likely that will occur during a period of high volatility for equities, but one that has also experienced great returns. Thus, our investor would be abandoning equities when his recent experience would suggest otherwise. And since timing can never be perfect, it is further likely that the equities he abandons will continue to outperform for some period. On an absolute basis, equities may rank best, but on a risk-adjusted basis, they may not. It is not uncommon for investors to ignore risk in such a situation, to their subsequent regret.

Ranking is not without its problems. For example, if you are selecting the top 4 groups of whatever category, there is a fair chance that at some time the assets ranked 4 and 5 will change places back and forth on a daily basis. This "flutter" can be easily solved by providing those who make the cut with a subsequent incumbency advantage. For a newcomer to replace a list member, it then must outrank the current assets on the selected list by the incumbency advantage. This is very similar to the manner in which thermostats work. We have found adding an incumbency advantage to be a profitable improvement without considering transactions costs. When one also considers the reduced transaction costs, the benefits increase even more.

Another important consideration is the "lookback" period. Above we used the example of our savvy investor ranking assets on the basis of their quarterly growth. Not surprisingly, the choice of a lookback period can have an effect on profitability. Since markets tend to fall more abruptly than they rise, lookback periods that perform best during rising markets are markedly different from those that perform best during falling markets. Determining whether a market is rising or falling can be problematic, as it can only be done with certainty in retrospect. However, another key factor influencing the choice of a lookback period is volatility, which can be determined concurrently. Thus an optimal lookback period can be automatically determined based on volatility.

There is certainly no question that a diligent investor can outperform the market. By outperforming the market we mean that he will achieve a greater average rate of return than the market, while limiting the maximum drawdown (or percentage equity decline) to less than that experienced by the market. But the average investor is generally not up to the diligence or persistence required.

In the research work illustrated above, all transactions were executed on the close of the day following a decision being made. Thus the strategy illustrated is certainly executable. Nothing required a forecast; all that was required was for the investor to recognize concurrently which assets have performed well over a recent period. It is not difficult, but requires daily monitoring.

www.mathinvestdecisions.com/about.htm

Charles Pennington writes:

Referring to the MathInvestor's plot:

www.mathinvestdecisions.com/Worst_6_of_10.gif :

At first glance it appears that the "Best" have been beating the "Worst" consistently.

In fact, however, all of the outperformance was from 1990 through 1995. From 1996 to present, it was approximately a tie.

Reading from the plot, I see that the "Best" portfolio was at about 2.1 at the start of 1996. It grew to about 5.5 at the end of the chart for a gain of about 160%. Over the same period, the "Worst" grew from 1.3 to 3.2, a gain of about 150%, essentially the same.

So for the past 11 years, this system had negligible outperformance.

One should also consider that the "Best" portfolio benefits in the study from stale pricing, which one could not capture in real trading. Furthermore, dividends were not included in the study. My guess is that the "Worst" portfolio would have had a higher dividend yield.

In order to improve this kind of study, I would recommend:

1.) Use instruments that can actually be traded, rather than S&P sectors, in order to eliminate the stale pricing concern.

2.) Plot the results on a semilog graph. That would have made it clear that all the outperformance happened before 1996.

3.) Finally, include dividends. The reported difference in compound annual returns (10.8% vs 8.0%) would be completely negated if the "Worst" portfolio had a yield 2.8% higher than the "Best".

Bill Rafter replies:

Gentlemen, please! The previously sent illustration of asset ranking is not a proposed "system," but simply an illustration that tilting one's portfolio away from dogs and toward previous performers can have a beneficial effect on the portfolio. The comparison between the 10 Sectors and the 24 Industry Groups illustrates the benefits of focus. That is, (1) don't buy previous dogs, and (2) sharpen your investment focus. Ignore these points and you will be leaving money on the table.

We have done this work with many different assets such as ETFs and even Fidelity funds (which require a 30-day holding period), both of which can be realistically traded. They are successful, but not overwhelmingly so. Strangely, one of the best asset groups to trade in this manner would be proprietarily-traded small-cap funds.

Unfortunately if you try trading those, your broker will disown you. I mention that example only to suggest that some assets truly do have "legs," or "tails" if you prefer. I think their success is attributed to the fact that some prop traders are better than others, and ranking them works. An asset group with which we have had no success is high-yield debt funds. I have no idea why.

A comment from Jerry Parker:

I wrote an initial comment to you via your website [can be found under the comments link by the title of this post], disputing your point of view, which a friend of mine read, and sent me the following:

I wrote an initial comment to you via your website [can be found under the comments link by the title of this post], disputing your point of view, which a friend of mine read, and sent me the following:

I read your comment on Niederhoffer's Daily Spec in response to his arguments against trend following. Personally, I don't think it boils down to intelligence, but rather to ego. Giving up control to an ego-less computer is not an easy task for someone who believes so strongly in the ability of the human mind. I have great respect for his work and his passion for self study, but of course disagree with his thoughts on trend following. On each trade, he is only able to profit if it "trends" in a favorable direction, whether the holding period is 1 minute or 1 year. Call it what you will, but he trades trends all day.

He's right. I was wrong. Trend following is THE enemy of the 'genius'. You and your friends can't even see how stupid your website is. You are blinded by your superior intelligence and arrogance.

Victor Niederhoffer responds:

Thanks much for your contributions to the debate. I will try to improve my understanding of this subject and my performance in the future so as not to be such an easy target for your critiques.

Ronald Weber writes:

When you think about it, most players in the financial industry are nothing but trend followers (or momentum-players). This includes analysts, advisors, relationship managers, and most fund or money managers. If there is any doubt, check the EE I function on Bloomberg, or the money flow/price functions of mutual funds.

When you think about it, most players in the financial industry are nothing but trend followers (or momentum-players). This includes analysts, advisors, relationship managers, and most fund or money managers. If there is any doubt, check the EE I function on Bloomberg, or the money flow/price functions of mutual funds.

The main reason may have more to do with career risk and the clients themselves. If you're on the right side while everyone is wrong, you will be rewarded; if you're on the wrong side like most of your peers you will be ok; and if you're wrong while everyone is right then you're in trouble!

In addition, most normal human beings (daily specs not included!) don't like ideas that deviate too much from the consensus. You are considered a total heretic if you try to explain why, for example, there is no link between the weak USD and the twin deficits. This is true, too, if you would have told anyone in 2002 that the Japanese banks will experience a dramatic rebound like the Scandinavian banks in the early '90s, and so on, or if you currently express any doubt on any commodity.

So go with the flow, and give them what they want! It makes life easier for everyone! If you can deal with your conscience of course!

The worse is that you tend to get marginalized when you express doubt on contagious thoughts. You force most people to think. You're the boring party spoiler! It's probably one reason why the most successful money managers or most creative research houses happen to be small organizations.

Jeremy Smith offers:

![]() Not arguing one way or the other here, but for any market or any stock that is making all time highs (measured for sake of argument in years) do we properly say about such markets and stocks that there is no trend?

Not arguing one way or the other here, but for any market or any stock that is making all time highs (measured for sake of argument in years) do we properly say about such markets and stocks that there is no trend?

Vincent Andres contributes:

I would distinguish/disambiguate drift and trend.

"Drift": Plentifully discussed here. "Trend": See arcsine, law of series, etc.

In 2D, the French author Jean-Paul Delahaye speaks about "effet rateau" (rake effect), here and here .

Basically, our tendency is to believe that random equals equiprobability everywhere (2D) or random equals equiprobability everytime (1D), and thus that nonequiprobability everywhere/everytime equals non random

In 1D, non equiprobability everytime means that the sequence -1 +1 -1 +1 -1 +1 -1 +1 is in fact the rare and a very non random sequence, while the sequences -1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 -1 +1 with a "trend" are in fact the truly random ones. By the way, this arcsine effect does certainly not explain 100% of all the observed trends. There may also be true ones. Mistress would be too simple. True drift may certainly produce some true trends, but certainly far less than believed by many.

Dylan Distasio adds:

For those who don't believe trend following can be a successful strategy, how would you explain the long-term performance of the No Load Fund X newsletter? Their system consists of a fairly simple relative strength mutual fund (and increasingly ETF) model where funds are held until they weaken enough in relative strength to swap out with new ones.

For those who don't believe trend following can be a successful strategy, how would you explain the long-term performance of the No Load Fund X newsletter? Their system consists of a fairly simple relative strength mutual fund (and increasingly ETF) model where funds are held until they weaken enough in relative strength to swap out with new ones.

The results have been audited by Hulbert and consistently outperform the S&P 500 over a relatively long time frame (1980 onwards). I think their results make a trend following approach worth investigating…

Jerry Parker comments again:

All you are saying is that you're not smart enough to develop a trend following system that works. What do you say about the billions of dollars traded by trend following CTAs and their long term track records?

Steve Leslie writes:

If the Chair is not smart enough to figure out trend following, what does that bode for the rest of us?

If the Chair is not smart enough to figure out trend following, what does that bode for the rest of us?

There is a very old yet wise statement: Do not confuse brains with a bull market.

Case in point: prior to 2000 the great tech market run was being fueled by the hysteria surrounding Y2K. Remember that term? It is not around today but it was the cause for the greatest bull market seen in stocks ever. Dot.com stocks and new issues were being bought with reckless abandon.

New issues were priced overnight and would open 40-50 points higher the next trading day. Money managers had standing orders to buy any new issues. There was no need for dog-and-pony or road shows. It was an absolute classic and chaotic case of extraordinary delusion and crowd madness.

Due diligence was put on hold, or perhaps abandoned. A colleague of mine once owned enough stock in a dot.com that had he sold it at a propitious time, he would have had enough money to purchase a small Hatteras yacht. Today, like many contemporary dot.coms, that stock is essentially worthless. It would not buy a Mad magazine.

Corporations once had a virtual open-ended budget to upgrade their hardware and software to prepare for the upcoming potential disaster. This liquidity allowed service companies to cash in by charging exorbitant fees. Quarter to quarter earnings comparisons were beyond belief and companies did not just meet the numbers, they blew by them like rocket ships. What made it so easy to make money was that when one sold a stock, all they had to do was purchase another similar stock that also was accelerating. The thought processes where so limited. Forget value investing; nobody on the planet wanted to talk to those guys. The value managers had to scrape by for years while they saw their redemptions flow into tech, momentum, and micro cap funds. It became a Ponzi scheme, a game of musical chairs. The problem was timing.

The music stopped in March of 2000 when CIO's need for new technology dried up coincident with the free money, and the stock market went into the greatest decline since the great depression. The NASDAQ peaked around 5000. Today it hovers around 2500, roughly half what it was 7 years ago.

It was not as if there were no warning signs. Beginning in late 1999, the tech market began to thin out and leadership became concentrated in a few issues. Chief among the group were Cisco, Oracle, Qwest, and a handful of others. Every tech, momentum, and growth fund had those stocks in their portfolio. This was coincident with the smart money selling into the sectors. The money managers were showing their hands if only one could read between the lines. Their remarks were "these stocks are being priced to perfection." They could not find compelling reasons not to own any of these stocks. And so on and on it went.

After 9/11 markets and industries began to collapse. The travel industry became almost nonexistent. Even Las Vegas went on life support. People absolutely refused to fly. Furthermore, business in and around New York City was in deep peril. This forced the Fed to begin dramatically reducing interest rates to reignite the economy. It worked, as corporations began to refinance their debt and restructure loans, etc.

The coincident effect began to show up in the housing industry. Homeowners refinanced their mortgages (yours truly included) and took equity out of their homes. Home-buyers were thirsty for real estate and bought homes as if they would disappear off the earth. For $2000 one could buy an option on a new construction home that would not be finished for a year. "Flipping" became the term du jour. Buy a home in a hot market such as Florida for nothing down and sell it six months later at a much higher price. Real estate was white hot. Closing on real estate was set back weeks and weeks. Sellers had multiple offers on their homes many times in the same day. This came to a screeching halt recently with the gradual rise in interest rates and the mass overbuilding of homes, and the housing industry has slowed dramatically.

Houses for sale now sit on the blocks for nine months or more. Builders such as Toll, KB, and Centex have commented that this is the worst real estate market they have seen in decades. Expansion plans have all but stopped and individuals are walking away from their deposits rather than be upside down in their new home.

Now we have an ebullient stock market that has gone nearly 1000 days without so much as a 2% correction in a day. The longest such stretch in history. What does this portend? Time will tell. Margin debt is now at near all-time highs and confidence indicators are skewed. Yet we hear about trend followers and momentum traders and their success. I find this more than curious. One thing that they ever fail to mention is that momentum trading and trend following does not work very well in a trendless market. I never heard much about trend followers from June 2000 to October 2002. I am certain that this game of musical chairs will end, or at least be temporarily interrupted.

As always, it is the diligent speculator who will be prepared for the inevitable and capitalize upon this event. Santayana once said, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

From "A Student:"

Capitalism is the most successful economic system in the history of the world. Too often we put technology up as the main driving force behind capitalism. Although it is true that it has much to offer, there is another overlooked hero of capitalism. The cornerstone of capitalism is good marketing.

Capitalism is the most successful economic system in the history of the world. Too often we put technology up as the main driving force behind capitalism. Although it is true that it has much to offer, there is another overlooked hero of capitalism. The cornerstone of capitalism is good marketing.

The trend following (TF) group of fund managers is a perfect example of good marketing. As most know, the group as a whole has managed to amass billions of investor money. The fund operators have managed to become wealthy through high fees. The key to this success is good marketing not performance. It is a tribute to capitalism.

The sports loving fund manger is a perfect example. All of his funds were negative for 2006 and all but one was negative over the last 3 years! So whether one looks at it from a short-term one year stand point or a three year perspective his investors have not made money. Despite this the manager still made money by the truckload during this period. Chalk it up to good marketing, it certainly was not performance.

The secret to this marketing success is intriguing. Normally hedge funds and CTAs cannot solicit investors nor even publicly tout their wares on an Internet site. The TF funds have found a way around this. There may be a web site which openly markets the 'concept' of TF but ostensibly not the funds. On this site the names of the high priests of TF are repeatedly uttered with near religious reverence. Thus this concept site surreptitiously drives the investors to the TF funds.

One of the brilliant marketing tactics used on the site is the continuous repetition of the open question, "Why are they (TF managers) so rich?" The question is offered as a sophist's response to the real world question as to whether TF makes money. The marketing brilliance lies in the fact that there is never a need to provide factual support or performance records. Thus the inconvenient poor performance of the TF funds over the last few years is swept under the carpet.

Also swept under the rug are the performance figures for once-great trend followers who no longer are among the great, i.e., those who didn't survive. Ditto for the non-surviving funds in this or that market from the surviving trend followers.

Another smart technique is how the group drives investor traffic to its concept site. Every few years a hagiographic book is written which idolizes the TF high priests. It ostensibly offers to reveal the hidden secrets of TF.

Yet after reading the book the investor is left with no usable information, merely a constant repetition of the marketing slogan: How come these guys are so rich? Obviously the answer is good marketing but the the book is moot on the subject. Presumably, the books are meant to be helpful and the authors are true believers without a tie-in in mind. But the invisible hand of self-interest often works in mysterious ways.

In the latest incarnation of the TF book the author is presented as an independent researcher and observer. Yet a few days after publication he assumes the role of Director of Marketing for the concept site. Even the least savvy observer must admit that it is extraordinary marketing when one can persuade the prospect to pay $30 to buy a copy of the marketing literature.

Jason Ruspini adds:

![]() "I attribute much of the success of the selected bigs to being net long leveraged in fixed income and stocks during the relevant periods."

"I attribute much of the success of the selected bigs to being net long leveraged in fixed income and stocks during the relevant periods."

I humbly corroborate this point. If one eliminates long equity, long fixed income (and fx carry) positions, most trend-following returns evaporate.

Metals and energies have helped recently, after years of paying floor traders.

Victor replies:

I don't agree with all the points above. For example, the beauty of capitalism is not its puffery, but the efficiency of its marketing and distribution system as well as the information and incentives that the prices provide so as to fulfill the pitiless desires of the consumers. Also beautiful is in the mechanism that it provides for those with savings making low returns to invest in the projects of entrepreneurs with much higher returns in fields that are urgently desired by customers.

I don't agree with all the points above. For example, the beauty of capitalism is not its puffery, but the efficiency of its marketing and distribution system as well as the information and incentives that the prices provide so as to fulfill the pitiless desires of the consumers. Also beautiful is in the mechanism that it provides for those with savings making low returns to invest in the projects of entrepreneurs with much higher returns in fields that are urgently desired by customers.

I have been the butt of abuse and scorn from the trend followers for many years. One such abusive letter apparently sparked the writer's note. Aside from my other limitations, the trend following followers apparently find my refusal to believe in the value of any fixed systems a negative. They also apparently don't like the serial correlation coefficients I periodically report that test the basic tenets of the trend following canon.

I believe that if there are trends, then the standard statistical methods for detecting same, i.e., correlograms, regressions, runs and turning point tests, arima estimates, variance ratio tests, and non-linear extensions of same will show them.

Such tests as I have run do not reveal any systematic departures from randomness. Nor if they did would I believe they were predictive, especially in the light of the principle of ever changing cycles about which I have written extensively.

Doubtless there is a drift in the overall level of stock prices. And certain fund managers who are biased in that direction should certainly be able to capture some of that drift to the extent that the times they are short or out of the market don't override it. However, this is not supportive of trend following in my book.

Similarly, there certainly has been over the last 30 years a strong upward movement in fixed income prices. To the extent that a person was long during this period, especially if on leverage, there is very good reason to believe that they would have made money, especially if they limited their shorts to a moiete.

Many of the criticisms of my views on trend following point to the great big boys who say they follow trends. To the extent that those big boys are not counterbalanced by others bigs who have lost, I attribute much of the success of the selected bigs to being net long leveraged in fixed income and stocks during the relevant periods.

I have no firm belief as to whether such things as trends in individual stocks exist. The statistical problem is too complex for me because of a paucity of independent data points, and the difficulties of maintaining an operational prospective file.

Neither do I have much conviction as to whether trends exist in commodities or foreign exchange. The overall negative returns to the public in such fields seem to be of so vast a magnitude that it would not be a fruitful line of inquiry.

If I found such trends through the normal statistical methods, I would suspect them as a lure of the invisible evil hand to bring in big money to follow trends after a little money has been made by following them, the same way human imposters work in other fields. I believe that such a tendency for trend followers to lose with relatively big money after making with smaller amounts is a feature of all fixed systems. And it's guaranteed to happen by the law of ever-changing cycles.

The main substantive objection to my views that I have found in the past, other than that trend followers know many people who make money following trends (a view which is self-reported and selective and non-systematic, and thus open to some of the objections of those of the letter-writer), is that they themselves follow trends and charts and make much money doing it. What is not seen by these in my views is what they would have made with their natural instincts if they did not use trend following as one of their planks. This is a difficult argument for them to understand or to confirm or deny.

My views on trend following are always open to new evidence, and new ways of looking at the subject. I solicit and will publish all views on this subject in the spirit of free inquiry and mutual education.

Jeff Sasmor writes:

![]() Would you really call what FUNDX does trend following? Well, whatever they do works.

Would you really call what FUNDX does trend following? Well, whatever they do works.

I used their system successfully in my retirement accounts and my kids' college UTMA's and am happy enough with it that I dumped about 25% of that money in their company's Mutual Funds which do the same process as the newsletter. The MFs are like an FOF approach. The added expense charges are worth it. IMO, anyway. Their fund universe is quite small compared to the totality of funds that exist, and they create classes of funds based on their measure of risk.

This is what they say is their process. When friends ask me what to buy I tell them to buy the FUNDX mutual fund if their time scale is long. No one has complained yet!

It ain't perfect (And what is? unless your aim is to prove that you're right) but it's better than me fumfering around trying to pick MFs from recommendations in Money Magazine, Forbes, or Morningstar.

I'm really not convinced that what they do is trend following though.

Dylan Distasio Adds:

For those who don't believe trend following can be a successful strategy, how would you explain the long-term performance of the No Load Fund X newsletter?

For those who don't believe trend following can be a successful strategy, how would you explain the long-term performance of the No Load Fund X newsletter?

Michael Marchese writes:

In a recent post, Mr. Leslie finished his essay with, "I never heard much about trend followers from June 2000 to October 2002." This link shows the month-to-month performance of 13 trend followers during that period of time. It seems they did OK.

Hanny Saad writes:

Not only is trend following invalid statistically but, looking at the bigger picture, it has to be invalid logically without even running your unusual tests.

Not only is trend following invalid statistically but, looking at the bigger picture, it has to be invalid logically without even running your unusual tests.

If wealth distribution is to remain in the range of 20 to 80, trend following cannot exist. In other words, if the majority followed the trend (hence the concept of trends), and if trend following is in fact profitable, the majority will become rich and the 20-80 distribution will collapse. This defeats logic and history. That said, there is the well-covered (by the Chair) general market upward drift that should also come as no surprise to the macro thinkers. The increase in the general population, wealth, and the entrepreneurial spirit over the long term will inevitably contribute to the upward drift of the general market indices as is very well demonstrated by the triumphal trio.

While all world markets did well over the last 100 yrs, you notice upon closer examination that the markets that outperformed were the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The one common denominator that these countries have is that they are all immigration countries. They attract people.

Contrary to what one hears about the negative effects of immigration, and how immigrants cause recessions, the people who leave their homelands looking for a better life generally have quite developed entrepreneurial spirits. As a result, they contribute to the steeper upward curve of the markets of these countries. When immigrants are allowed into these countries, with their life savings, home purchases, land development, saving and borrowing, immigration becomes a rudder against recession, or at least helps with soft landings. Immigration countries have that extra weapon called LAND.

So in brief, no - trends do not exists and can not exist either statistically or logically, with the exception of the forever upward drift of population and general markets with some curves steeper than others, those of the countries with the extra weapon called land and immigration.

A rereading of The Wealth And Poverty Of Nations, by Landes, and the triumph of the optimist may be in order.

Steve Ellison adds:

So Mr. Parker's real objective was simply to insult the Chair, not to provide any evidence of the merits of trend following that would enlighten us (anecdotes and tautologies that all traders can only profit from favorable trends prove nothing). I too lack the intelligence to develop a trend following system that works. When I test conditions that I naively believe to be indicative of trends, such as crossovers of moving averages, X-day highs and lows, and the direction of the most recent Y percent move, I usually find negative returns going forward.

So Mr. Parker's real objective was simply to insult the Chair, not to provide any evidence of the merits of trend following that would enlighten us (anecdotes and tautologies that all traders can only profit from favorable trends prove nothing). I too lack the intelligence to develop a trend following system that works. When I test conditions that I naively believe to be indicative of trends, such as crossovers of moving averages, X-day highs and lows, and the direction of the most recent Y percent move, I usually find negative returns going forward.

Bacon summarized his entire book in a single sentence: "Always copper the public play!" My more detailed summary was, "When the public embraces a particular betting strategy, payoffs fall, and incentives (for favored horsemen) to win are diminished."

Trend Following — Cause, from James Sogi:

Generate a Brownian motion time series with drift in R

WN <-rnorm(1024);RW<-cumsum(WN);DELTAT<-1/252;

MU<-.15*DELTAT;SIG<-.2*sqrt(DELTAT);TIME<-(1:1024)/252 stock<-exp(SIG*RW+MU*TIME) ts.plot(stock)

Run it a few times. Shows lots of trends. Pick one. You might get lucky.

Trend Following v. Buy and Hold, from Yishen Kuik

The real price of pork bellies and wheat should fall over time as innovation drives down costs of production. Theoretically, however, the nominal price might still show drift if the inflation is high enough to overcome the falling real costs of production.

I've looked at the number of oranges, bacon, and tea a blue collar worker's weekly wages could have purchased in New York in 2000 versus London in the 1700s. All quantities showed a significant increase (i.e., become relatively cheaper), lending support to the idea that real costs of production for most basic foodstuffs fall over time.

Then again, according to Keynes, one should be able to earn a risk premium from speculating in commodity futures by normal backwardation, since one is providing an insurance service to commercial hedgers. So one doesn't necessarily need rising spot prices to earn this premium, according to Keynes.

Not All Deer are Five-Pointers, from Larry Williams

What's frustrating to me about trading is having a view, as I sometimes do, that a market should be close to a short term sell, yet I have no entry. This betwixt and between is frustrating, wanting to sell but not seeing the precise entry point, and knowing I may miss the entry and then see the market decline.

What's frustrating to me about trading is having a view, as I sometimes do, that a market should be close to a short term sell, yet I have no entry. This betwixt and between is frustrating, wanting to sell but not seeing the precise entry point, and knowing I may miss the entry and then see the market decline.

So I wait. It's hard to learn not to pull the trigger at every deer you see. Not all are five-pointers… and some will be bagged by better hunters than I.

From Gregory van Kipnis:

Back in the 70s a long-term study was done by the economic consulting firm of Townsend Greenspan (yes, Alan's firm) on a variety of raw material price indexes. It included the Journal of Commerce index, a government index of the geometric mean of raw materials and a few others. The study concluded that despite population growth and rapid industrialization since the Revolutionary War era, that supply, with a lag, kept up with demand, or substitutions (kerosene for whale blubber) would emerge, which net-net led to raw material prices being a zero sum game. Periods of specific commodity price rises were followed by periods of offsetting declining prices. That is, raw materials were not a systematic source of inflation independent of monetary phenomena.

Back in the 70s a long-term study was done by the economic consulting firm of Townsend Greenspan (yes, Alan's firm) on a variety of raw material price indexes. It included the Journal of Commerce index, a government index of the geometric mean of raw materials and a few others. The study concluded that despite population growth and rapid industrialization since the Revolutionary War era, that supply, with a lag, kept up with demand, or substitutions (kerosene for whale blubber) would emerge, which net-net led to raw material prices being a zero sum game. Periods of specific commodity price rises were followed by periods of offsetting declining prices. That is, raw materials were not a systematic source of inflation independent of monetary phenomena.

It was important to the study to construct the indexes correctly and broadly, because there were always some commodities that had longer-term rising trends and would bias an index that gave them too much weight. Other commodities went into long-term decline and would get dropped by the commodity exchanges or the popular press. Just as in indexes of fund performance there can be survivor bias, so too with government measures of economic activity and inflation.

However, this is not to say there are no trends at the individual commodity level of detail. Trends are set up by changes in the supply/demand balance. If the supply/demand balance changes for a stock or a commodity, its price will break out. If it is a highly efficient market, the breakout will be swift and leave little opportunity for mechanical methods of exploitation. If it is not an efficient market (for example, you have a lock on information, the new reality is not fully understood, the spread of awareness is slow, or there is heavy disagreement, someone big has to protect a position against an adverse move) the adjustment may be slower to unfold and look like a classic trend. This more often is the case in commodities.

Conversely, if you find a breakout, look for supporting reasons in the supply/demand data before jumping in. But, you need to be fast. In today's more highly efficient markets the problem is best summarized by the paradox: "look before you leap; but he who hesitates is lost!"

Larry Williams adds:

I would posit there is no long-term drift to commodities and thus we have a huge difference in these vehicles.

The commodity index basket guys have a mantra that commodities will go higher - drift - but I can find no evidence that this is anything but a dream, piquant words of promotion that ring true but are not.

I anxiously stand to be corrected.

Marlowe Cassetti writes:

"Along a similar vein, why would anybody pay Powershares to do this kind of work when the tools to do it yourself are so readily available?"

The simple answer is if someone wishes to prescribe to P&F methodology investing, then an ETF is a convenient investment vehicle.

With that said, this would be an interesting experiment. Will the DWA ETF be another Value Line Mutual Fund that routinely fails to beat the market while their newsletter routinely scores high marks? There are other such examples, such as IBD's William O'Neal's aborted mutual fund that was suppose to beat the market with the fabulous CANSLIM system. We have talked about the great track record of No-Load Fund-X newsletter, and their mutual fund, FUNDX, has done quite well in both up and down markets (an exception to the above mentioned cases).

For full disclosure I have recently added three of their mutual funds to my portfolio FUNDX, HOTFX, and RELAX. Hey, I'm retired and have better things to do than do-it-yourself mutual fund building. With 35 acres, I have a lot of dead wood to convert into firewood. Did you know that on old, dead juniper tree turns into cast iron that dulls a chain saw in minutes? But it will splinter like glass when whacked with a sledgehammer.

Kim Zussman writes:

…about the great track record of No-Load Fund-X newsletter and their mutual fund FUNDX has done quite well in both up and down markets… (MC)

Curious about FUNDX, checked its daily returns against ETF SPY (essentially large stock benchmark).

Regression Analysis of FUNDX versus SPY since inception, 6/02 (the regression equation is FUNDX = 0.00039 + 0.158 SPY):

Predictor Coef SE Coef T P

Constant 0.00039 0.000264 1.48 0.14

SPY 0.15780 0.026720 5.91 0.00

S = 0.00901468 R-Sq = 2.9% R-Sq (adj) = 2.8%

The constant (alpha) is not quite significant, but it is positive, so FUNDX did out-perform SPY. Slope is significant and the coefficient is about 0.16, which means FUNDX was less volatile than SPY.

This is also shown by F-test for variance:

Test for Equal Variances: SPY, FUNDX

F-Test (normal distribution) Test statistic = 1.17, p-value = 0.009 (FUNDX<SPY)

But t-test for difference between daily returns shows no difference:

Two-sample T for SPY vs FUNDX

N Mean St Dev SE Mean

SPY 1169 0.00041 0.0099 0.00029

FUNDX 1169 0.00045 0.0091 0.00027 T=0.12

So it looks like FUNDX has been giving slight/insignificant out-performance with significantly less volatility; which makes sense since it is a fund of mutual funds and ETFs.

Even better is Dr Bruno's idea of beating the index by deleting the worst (or few worst) stocks (new additions?).

How about an equal-weighted SP500 (which out-performs when small stocks do), without the worst 50 and double-weighting the best 50.

Call it FUN-EX, in honor of the fun you had with your X that was all mooted in the end.

Alex Castaldo writes:

The results provided by Dr. Zussman are fascinating:

The fund has a Beta of only 0.157, incredibly low for a stock fund (unless they hold a lot of cash). Yet the standard deviation of 0.91468% per day is broadly consistent with stock investing (S&P has a standard deviation of 1%). How can we reconcile this? What would Scholes-Williams, Dimson, and Andy Lo think when they see such a low beta? Must be some kind of bias.

I regressed the FUNDX returns on current and lagged S&P returns a la Dimson (1979) with the following results:

Regression Statistics

Multiple R 0.6816

R Square 0.4646

Adjusted R Square 0.4627

Standard Error 0.0066

Observations 0.1166

ANOVA

df SS MS F Significance F

Regression 4 0.0444 0.0111 251.89 8.2E-156

Residual 1161 0.0511 4.4E-05

Total 1165 0.0955

Coefficients Standard Error t-Stat P-value

Intercept 8.17E-05 0.000194 0.4194 0.6749

SPX 0.18122 0.019696 9.2007 1.6E-19

SPX[-1] 0.60257 0.019719 30.5566 6E-151 SPX[-2] 0.08519 0.019692 4.3260 1.648E-05 SPX[-3] 0.04524 0.019656 2.3017 0.0215

Note the following:

(1) All four S&P coefficients are highly significant.

(2) The Dimson Beta is 0.914 (the sum of the 4 SPX coefficients). The mystery of the low beta has been solved.

(3) The evidence of price staleness, price smoothing, non-trading, whatever you want to call it is clear. Prof. Pennington touched on this the other day; an "efficiently priced" asset should not respond to past S&P price moves. Apparently though, FUNDX holds plenty of such assets (or else the prices of FUNDX itself, which I got from Yahoo, are stale).

S. Les writes:

Have to investigate the Fund X phenomenon. And look to see how it has done in last several years since it was post selected as good. Someone has to win a contest, but the beaten favorites are always my a priori choice except when so many others use that as a system the way they do in sports eye at the harness races, in which case waiting for two races or two days seems more apt a priori. VN

I went to the Fund X website to read up, and the information is quite sparse. It is a very attenuated website. I called the toll free number and chatted with the person on the other line. Information was OK, but, in my view, I had to ask the proper questions. One has several options here. One is to purchase the service and do the fund switching themselves based on the advice of their experts. The advisory service tracks funds that have the best relative strength performance and makes their recommendations from there, www.fundx.com.

Another is to purchase one of four funds available. They have varying levels of aggressiveness. Fund 3 appears to be the recommended one.

If one purchases the style 3 one will get a very broad based fund of funds. I went to yahoo to look up the holdings at www.finance.yahoo.com/q/hl?s=FUNDX.

Top ten holdings are 47.5% of the portfolio, apparently concentrated in emerging markets and international funds at this time.

In summary, if money were to be placed into the Fund X 3 portfolio, I believe it would be so broad based and diversified that returns would be very watered down. Along with risk you would certainly be getting a lot of funds. You won't set the world on fire with this concept, but you won't get blown up, either.

Larry Williams adds:

My 2002 book, Right Stock at the Right Time, explains such an approach in the Dow 30. The losers were the overvalued stocks in the Dow.It is a simple and elegant idea…forget looking for winners…just don't buy overvalued stocks and you beat the idex.

This notion was developed in 1997, when i began actually doing it, and written about in the book. This approach has continued to outperform the Dow, it is fully revealed.

Craig Cuyler writes:

Larry's comment on right stock right time is correct and can be used to shed a little bit of light on trend following. This argument is at the heart of fundamental indexation, which amongst other points argues that cap weighting systematically over-weights overvalued stocks and under-weights undervalued stocks in a portfolio.

Only 29% of the top 10 stocks outperformed the market average over a 10yr period (1964-2004) according to Research Affiliates (this is another subject). The concept of "right stock right time" might be expressed another way, as "right market right time." The point is that constant analysis needs to take place for insuring investment in the products that are most likely to give one a return.

The big error that the trend followers make, in my mind, is they apply a homogeneous methodology to a number of markets and these are usually the ones that are "hot" at the time that the funds are applied. The system is then left to its own devices and inevitably breaks down. Most funds will be invested at exactly the time when the commodity, currencies, etc., are at their most overvalued.

Some worthwhile questions are: How does one identify a trend? Why is it important that one identifies a trend? How is it that security trends allow me to make money? In what time frame must the trend take place and why? What exactly is a trend and how long must it last to be so labeled?

I think it is important to differentiate between speculation using leverage and investing in equities because, as Vic (and most specs on the list) point out, there is a drift factor in equities which, when using sound valuation principles, can make it easier to identify equities that have a high probability of trending. Trend followers don't wait for a security to be overvalued before taking profits. They wait for the trend to change before then trying to profit from the reversal.

Jeff Sasmor adds:

As a user of both the newsletter and the FUNDX mutual fund I'd like to comment that using the mutual fund removes the emotional component of me reading the newsletter and having to make the buys and sells. Perhaps not an issue for others, but I found myself not really able to follow the recommendations exactly - I tend to have an itchy trigger finger to sell things. This is not surprising since I do mostly short-term and day trades. That's my bias; I'm risk averse. So the mutual fund puts that all on autopilot. It more closely matches the performance of their model portfolio.

I don't know how to comment on the comparisons to Value Line Arithmetic Index (VAY). Does anyone follow that exactly as a portfolio?

My aim is to achieve reasonable returns and not perfection. I assume I don't know what's going to happen and that most likely any market opinion that I have is going to be wrong. Like Mentor of Arisia, I know that complete knowledge requires infinite time. That and beta blockers helps to remove the shame aspect of being wrong. But there's always an emotional component.

As someone who is not a financial professional, but who is asked what to buy by friends and acquaintances who know I trade daily (in my small and parasitical fashion), I have found that this whole subject of investing is opaque to most people. Sort of like how in the early days of computing almost no one knew anything about computers. Those who did were the gatekeepers, the high priests of the temple in a way. Most people nowadays still don't know what goes on inside the computer that they use every day. It's a black box - opaque. They rely on the Geek Squad and other professionals to help them out. It makes sense. Can't really expect most people to take the time to learn the subject or even want to. Should they care whether their SW runs on C++ or Python, or what the internal object-oriented class structure of Microsoft Excel is, or whether the website they are looking at is XHTML compliant? Heck no!

Similarly, most people don't know anything about markets; don't want to learn, don't want to take the time, don't have the interest. And maybe they shouldn't. But they are told they need to invest for retirement. As so-called retail investors they depend on financial consultants, fee-based planners, and such to tell them what to do. Often they get self-serving or become too loaded with fees (spec-listers who provide these services excepted).

So I think that the simple advice that I give, of buying broad-based index ETFs like SPY and IWM and something like FUNDX, while certainly less than perfect, and certainly less profitable than managing your own investments full-time, is really suitable for many people who don't really have the inclination, time, or ability to investigate the significant issues for themselves or sort out the multitudes of conflicting opinions put forth by the financial media.

You may not achieve the theoretical maximum returns (no one does), but you will benefit from the upward drift in prices and your blended costs will be reasonable. And it's better than the cash and CDs that a lot of people still have in their retirement accounts.

BTW: FOMA = Foma are harmless untruths, intended to comfort simple souls.

An example : "Prosperity is just around the corner."

I'm not out to defend FUNDX, I have nothing to do with them. I'm just happy with it.

Steve Ellison writes:

One might ask what the purpose of trends is in the market ecosystem. In the old days, trends occurred because information disseminated slowly from insiders to Wall Streeters to the general public, thus ensuring that the public lost more than it had a right to. Memes that capture the public imagination, such as Nasdaq in the 1990s, take years to work through the population, and introduce many opportunities for selling new investment products to the public.

Perhaps some amount of trending is needed from time to time in every market to keep the public interested and tossing chips into the market. I saw this statement at the FX Money Trends website on September 21, 2005: "[T]he head of institutional sales at one of the largest FX dealing rooms in the US … lamented that for the past 2 months trading volume had dried up for his firm dramatically because of the 'lack of trend' and that many 'system traders' had simply shut down to preserve capital."

I saw a similar dynamic recently at a craps table when shooters lost four or five consecutive points, triggering my stop loss so that I quit playing. About half the other players left the table at the same time. "The table's cold," said one.

To test whether a market might trend out of necessity to attract money, I used point and figure methodology with 1% boxes and one-box reversals on the S&P 500 futures. I found five instances in the past 18 months in which four consecutive reversals had occurred and tabulated the next four points after each of these instances (the last of which has only had three subsequent points so far). The results were highly non-predictive.

Starting Next 4 points

Date Continuations Reversals

01/03/06 3 1

05/23/06 1 3

06/29/06 2 2

08/15/06 2 2

01/12/07 1 2

—– —–

9 10

Anthony Tadlock writes:

I had intended to write a post or two on my recent two week trip to Cairo, Aswan, and Alexandria. There is nothing salient to trading but Egypt seems to have more Tourist Police and other guards armed with machine guns than tourists. It is a service economy with very few tourists or middle/upper classes to service. Virtually no westerners walk on the streets of Cairo or Alexandria. I did my best to ignore my investments and had closed all my highly speculative short-term trades before leaving for the trip.

While preparing for taxes I was looking over some of my trades for last year. Absolute worst trade was going long CVS and WAG too soon after WalMart announced $2 generic pricing. I had friends in town and wasn't able to spend my usual time watching and studying the market. I just watched them fall for two days and without looking at a chart, studying historical prices and determining how far they might fall, decided the market was being stupid and went long. Couldn't wait to tell my visitors how "smart" a trader I was and my expected profit. It was fun, until announcement after announcement by WalMart kept causing the stocks to keep falling. The result was panic selling near the bottom, even though I had told myself before the trade that I could happily buy and hold both. Basically, I followed all of Vic's rules on "How to Lose."

Trends: If only following a trend meant being able to draw a straight line or buy a system and buy green and sell red. The trend I wrote about several months ago about more babies being born of affluent parents still seems to be intact. I have recently seen pregnant moms pushing strollers again. Planes to Europe have been at capacity my last two trips and on both trips several crying toddlers made sleep difficult, in both directions. Are people with young children using their home as an ATM to fund a European trip? Are they racking up credit card debt that they can't afford? Depleting their savings? (Oh wait - Americans don't save anything.) If they are, then something fundamental has changed about how humans behave.

From James Sogi:

My daughter the PhD candidate at Berkeley in bio-chem is involved in some mind-boggling work. It's all very confidential, but she tried to explain to me some of her undergrad research in words less than 29 letters long. Molecules have shapes and fit together like keys. The right shape needs to fit in for a lock. Double helices of the DNA strand are a popular example, but it works with different shapes. There is competition to fit the missing piece. They talk to each other somehow. One of her favorite stories as a child was Shel Silverstein's Missing Piece. Maybe that's where her chemical background arose. Silverstein's imagery is how I picture it at my low level.

Looking at this past few months chart patterns it is impossible not to see the similarity in how the strands might try fit together missing pieces in Wykoffian functionality. The math and methods must be complicated, but might supply some ideas for how the ranges and strands in the market might fit together, and provide some predictive methods along the lines of biochemical probability theory. I'll need some assistance from the bio-chem section of the Spec-list to articulate this better.

From Kim Zussman:

Doing same as Alex Castaldo, using SPY daily change (cl-cl) as independent and FUNDX as dependent gave different resluts:

Regression Analysis: FUNDX versus SPY ret, SPY-1, SPY-2

The regression equation is FUNDX = 0.000383 + 0.188 SPY ret - 0.0502 SPY-1 - 0.0313 SPY-2

Predictor Coef SE Coef T P

Constant 0.000383 0.00029 1.35 0.179

SPY ret 0.187620 0.03120 6.01 0.000* SPY-1 -0.050180 0.03136 -1.60 0.110 SPY-2 -0.031250 0.03121 -1.00 0.317 *(contemporaneous)

S = 0.00970927 R-Sq = 3.2% R-Sq (adj) = 3.0%

Perhaps FUNDX vs a tradeable index is the explanation.

Feb

7

A New Regime, by Victor Niederhoffer

February 7, 2007 | 1 Comment

The stock market has emerged in last 5 days and it isn't captured, I dont think, by the normal things. Here are the high and low closes for recent days:

date open high low close

206 1454.0 1454.8 1447.8 1453.3

205 1451.5 1454.0 1448.1 1453.7

202 1452.2 1454.0 1448.1 1453.7

201 1446.3 1451.7 1444.0 1450.8

The average absolute change in highs, lows, and closed, from day to day, is 1. This has to be an all time non-holiday low. IBM also is trading at exactly 100 after swinging back and forth 4 times in last month above and below. What does it portend?

Not having any keys, although I do have the book by Ken Follett, I would like to consider some childlike questions about it. Others might think about this and the generalizations of same, I think, with value.

Sushil Kedia writes:

The lull before the storm. A single day's behaviour such as this would be dismissed as indecision.

Similarly, a second day would, at best, be termed market failed to get out of its indecision.

A third day again like this would make one tilt towards thinking the simplest of possible explanations, that a lull often is seen before the storm.

As distinct from any breakouts, which might not exist for a profit seeker, a simpler visualization appeals here. In ball games, from a football to a cricket ball, the point in the trajectory where a noticeable spin seems to be developing is a similar moment of quickly vanishing lull. Not a point of reversal, not a point of inflexion, just a point where the mistress will try to shuffle out the maximum number of players diving in either direction.

I clearly have no clue how I could translate this string of thought into a testable hypothesis.

Kim Zussman writes:

SPY, daily partitioned into 10d non-overlapping periods (from today's close) back to 2000; every 10d period checked standard deviation of daily closes, return for this 10 days, and return for next 10d.

Ten day return regressed against concurrent 10d standard deviation was negatively correlated (T=-1.9). Regression of next 10d return against prior 10d standard deviation and return showed positive correlation with prior standard deviation (t=1.8), and slight positive with prior 10d return (t=0.9).

Going to 5d non-overlapping, the current 5d standard deviation is 6th lowest of 352. The same regressions showed different results, with slight/NS correlation between 5d returns and concurrent standard deviation. The multiple regressions for next 5d return showed significant negative correlation with prior 5d return (t=-3), and slight positive/NS with prior 5d standard deviation (t=0.24).

So it looks like over short intervals, SPY returns related more to prior returns than volatility; but in longer intervals prior standard deviation is more important.

Vincent Andres writes:

"The average absolute change in highs, lows, and closed, from day to day, is 1. This has to be an all time non-holiday low. IBM also is trading at exactly 100 after swinging back and forth 4 times in last month above and below. What does it portend?

Not having any keys, although I do have the book by Ken Follett, I would like to consider some childlike questions about it. Others might think about this and the generalizations of same, I think, with value."

Some related thoughts:

1.) K. Lorenz often put emphasis on the pair: stimulus and duration (and duration is often considered on spec list). Not surprisingly, in general, the longer the duration, the smaller the needed stimulus to provoke an identical reaction. Maybe wrong, but I wouldn't be surprised if duration were often a good candidate to explain our stats, residues, and even more.

On more elaborated stimuli, K. Lorenz and Tinbergen speaks about "triggering schema" (schéma déclencheur). This concept may be an appropriate frame for some of our stimuli. Tinbergen got the Nobel Prize with Lorenz and Frisch. R. Dawkins was a student of Tinbergen.

2.) Remembering the previous "trend" thread, we may consider non-trending phases as quite rare events. So, if the stimulus part alone is rare, this seems a condition propitious for the whole pattern being non-random.

Apologies, no counts (… not yet).

PS: "I have found the missing link between the higher ape and civilized man: It is we." K. Lorenz.

Feb

5

Pain Frequency By Kim Zussman

February 5, 2007 | Leave a Comment

On 2/5/07, Andrea Ravano wrote:

Evidence from Capuchin Monkey Trading behavior: The study confirms for animals, what behavioral studies have shown for human beings; that to offset a loss of 1 you must have a profit 2.5 times as big. In other words the perception of your pain is greater than that of your pleasure.

That pain of loss is 2.5 greater than pleasure of gain, in absolute terms, has been bandied about in literature for a while. What is the nature of a trader's state of mind as a function of trading (or more specifically, position checking) frequency?

One check on this is to look at the effect of multiplying losses by 2, and comparing with gains scaled at 1. Using SPY returns since 1993, checked average returns for daily, weekly, and monthly intervals:

Daily Weekly Monthly

Ave: -0.003 -0.005 -0.002

Pos: 1855 411 411

Tot: 3529 730 169

%Pos: 52 56 65

When the "effect" of losses on your soul is double that of gains, you are suffering, on average, in all intervals. Therefore, it is no coincidence there are so many psychologists/psychiatrists involved in trading. Percentage of the positive, however, scales up with longer intervals, so you feel bad less often.

Philip McDonnell adds:

Consider what happens when you lose: How much is required to break even?

Loss Required Gain Ratio

-20% 25% 1.25

-25 33.3% 1.33

-50 100 2.00

-75 300 4.00

Average Ratio 2.15

The ratio of how much is required to break even rises rapidly as the losses increase. Although the above unscientific data points appear to be in the ball park of the putative 2.5 ratio, the underlying ratios are clearly non-linear and NOT well described by a simple number. In fact any simple ratio is far too simplistic to be a good measure.

I would argue that a log linear utility function is what an investor, and any rational individual, would want. In their famous paper on Prospect Theory, Kahnemann and Tversky identified what appeared to be irrational behavior on the part of university students and some faculty when presented with hypothetical bets. The Nobel Prize winning professors concluded that the students chose irrationally as compared to the Gold standard of statistical expectations based on an arithmetic utility of money.

But if money compounds, one would want a log utility of money. When the examples cited in the study were recalculated with a log utility based on the relative net worth of typical students the results showed that the student subjects were invariably quite consistent with a log utility function. This re-opens the question: Were the subjects or the professors the irrational ones?

If one expresses the gains and losses in the above table as the natural log of the price relative, then the negative logs of the losses exactly cancel the logs of the gains.

Charles Pennington adds:

These experiments that psychology professors run on students invariably involve the students' winning or losing maybe $100 or less. That's a small amount by any reasonable metric.

$100 is very small, for example, compared with their first year's salary out of school. So it's quite reasonable for the professors to assume that the amount is in the limit of a "small" amount, in the sense that it (1+x) is approximately x if x is "small."

Any reasonable person, offered the opportunity to bet with a 50% chance of winning $250 and a 50% chance of losing $100, should take the bet. That's true even if he only has $250 to his name, because he also has prospects for future earnings.

In this case, the professors are more rational than the monkeys.

J. T. Holley wrote:

"Could it be that all the bruised and battered hold-outs from '00 - '03 will finally join in, and we resume the incessant trek toward the summit of market-based capitalism?" kz

How about this simple fact: For the first time in recent years that I can remember, the Dow and S&P indexes (headline purposes) outperformed the price appreciation, across America, of houses or real estate. This is roughly a two to one ratio. Now for the sake of simplicity, how many of the '00 - '03 bruised and battered people are going to scratch their heads and say, "twice as much, huh?"

I think the "Confidence Index" mentioned by Carret has a ways to go fellas; but this must obviously be tested.

Philip McDonnell adds:

"Any reasonable person, offered the opportunity to bet with a 50% chance of winning $250 and a 50% chance of losing $100, should take the bet, and that's true even if he only has $250 to his name, because he also has prospects for FUTURE earnings."

I would agree that future earnings can be and perhaps should be factored in. But to a freshman with $100 (not $250) the 50% chance of no beer, pizza, and dating for four years might seem an unacceptable risk. Losing it all results in a utility of Ln (zero), the way I look at things. Ln asymptotically approaches negative infinity.

A few points:

1. KT did include some bets in the thousands of dollars.

2. Most of the KT bets were fairly close calls even viewed from an expected arithmetic value as opposed to a log utility.

3. KT never concluded that the indifference ratio was 2.5 or any other number in their ground-breaking paper.

Feb

5

Sunny Days, by Kim Zussman

February 5, 2007 | Leave a Comment

Currently we have strong earnings, tame inflation, a smug Fed showing signs of a Bernanke-put, high productivity without wage pressure, declining oil and commodity prices, new all-time high on Dow, new six year high on SP500, stock earnings yield higher than bonds, and near record low volatility. Tests of new highs, big advances, and consecutive up-months don't show any signs of trouble ahead.

Could it be that all the bruised and battered hold-outs from '00-'03 will finally join in and we resume the incessant trek toward the summit of market-based capitalism?

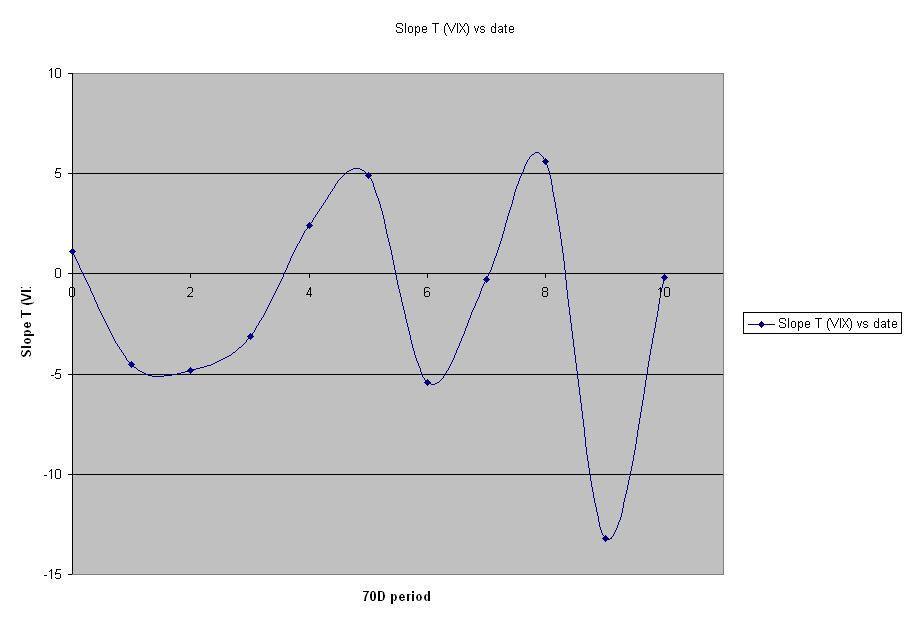

Looking further into VIX, partitioned daily VIX closes into ten non-overlapping 70 day periods, 1/04-present. For each period, the regressed VIX vs. date is shown, and it is noted whether the slope of the fitted line was significant (i.e. T<-2 means VIX declined significantly, T>2 means it went up). Here is the data for the ten periods, shown with corresponding slope T score:

Date VIX slopeT

10 -0.2 (period ending at present)

9 -13.2

8 5.6

7 -0.3

6 -5.4

5 4.9

4 2.4

3 -3.1

2 -4.8

1 -4.5

0 1.1 (starting 1/04)

These line segments follow rise and declines in volatility, as well as "flat" periods like the current one. Last summer's volatility spike shows in period eight, T = 5.6, followed famously by the decline of period nine (T = -13.2). Although there does appear to be some periodicity (see roller-coaster diagram), there are also consecutive runs of up and down slope.

Feb

2

How Often Do You Never Lose In 10 Years?, by Kim Zussman

February 2, 2007 | Leave a Comment

If you had bought the SP500 index at the end of each calendar week since 1950, in the ten years subsequent to each buy, how much of the time would you never go negative?

Using SP500 weekly closes up until 520 weeks ago (7/8/96), 277/2428 buys never saw red (11.4%). Another way to look at it is that for long-term investors, about 8/9 weekly stock purchases were underwater at some time during the next ten years.

This sounds rather unpleasant for holders of buying, however the return for the ten years (overlapping, for all weeks) averaged +40%, with 96% positive. The few negatives were the unlucky folks (like parents of someone close) who bought stocks in the mid 60's and held them to the mid-70's.

In memory of such long extinct anguish, here are the buy weeks which lost ten years later:

Date 10y ret

03/16/64 -0.21 (-21%)

05/18/64 -0.19

03/09/64 -0.18

05/25/64 -0.17

02/24/64 -0.16

06/08/64 -0.16

06/01/64 -0.15

05/04/64 -0.15

06/29/64 -0.14

05/11/64 -0.14

06/15/64 -0.13

07/06/64 -0.12

04/06/64 -0.12

06/22/64 -0.11

03/02/64 -0.10

04/27/64 -0.10

03/23/64 -0.10

03/30/64 -0.10

07/13/64 -0.08

04/13/64 -0.08

07/31/67 -0.08

02/17/64 -0.08

08/14/67 -0.08

09/11/67 -0.07

02/03/64 -0.07

09/18/67 -0.07

08/07/67 -0.07

02/10/64 -0.07

11/12/68 -0.06

04/20/64 -0.06

11/25/68 -0.06

07/20/64 -0.06

10/21/68 -0.05

09/05/67 -0.05

06/10/68 -0.05

12/02/68 -0.05

06/03/68 -0.05

02/23/65 -0.05

07/17/67 -0.05

07/24/67 -0.05

11/18/68 -0.05

07/10/67 -0.04

12/09/68 -0.04

04/29/68 -0.04

08/21/67 -0.04

10/14/68 -0.04

09/25/67 -0.04

08/28/67 -0.04

11/04/68 -0.04

02/01/65 -0.03

05/27/68 -0.03

09/14/64 -0.03

10/28/68 -0.03

10/02/67 -0.03

05/06/68 -0.03

12/16/68 -0.03

04/22/68 -0.03

09/30/68 -0.02

12/23/68 -0.02

05/17/65 -0.02

12/30/68 -0.02

07/27/64 -0.02

04/08/68 -0.02

07/03/67 -0.02

01/27/64 -0.02

08/12/68 -0.02

06/17/68 -0.02

01/25/65 -0.01

10/07/68 -0.01

03/08/65 -0.01

07/01/68 -0.01

04/07/69 -0.01

03/01/65 -0.01

06/26/67 -0.01

03/15/65 -0.01

07/15/68 -0.01

08/10/64 -0.01

01/18/65 -0.01

04/17/67 -0.01

02/15/65 -0.01

05/24/65 -0.01

05/13/68 -0.01

05/20/68 -0.01

Jan

30

Wait for a Big Date, by Kim Zussman

January 30, 2007 | Leave a Comment

Daily declines/advances bigger than 1% in SPY (close-close) were checked from 1/04 - present. Counting number of trading days between such moves, regressed wait time (days) vs. date:

Regression Analysis: wait versus Date

The regression equation is wait = - 252 + 0.00675 Date

Predictor Coef SE Coef T P

Constant -252.41 84.57 -2.98 0.004

Date 0.0067 0.0022 3.07 0.003

S = 7.11891 R-Sq = 8.1% R-Sq(adj) = 7.2

i.e., the wait time between big dates has increased in the period, which is consistent with (and correlates with, not shown) decline in standard deviation (volatility) in the period.

Here are the big dates:

Date big wait

01/25/07 -0.012 37

11/29/06 0.010 2

11/27/06 -0.014 14

11/06/06 0.011 23

10/04/06 0.012 35

08/15/06 0.012 16

07/24/06 0.018 3

07/19/06 0.014 4

07/13/06 -0.016 1

07/12/06 -0.011 8

06/29/06 0.020 10

06/15/06 0.021 2

06/13/06 -0.012 1

06/12/06 -0.011 5

06/05/06 -0.015 3

05/31/06 0.011 1

05/30/06 -0.018 2

05/25/06 0.012 6

05/17/06 -0.019 3

05/12/06 -0.013 1

05/11/06 -0.012 17

04/18/06 0.016 6

04/07/06 -0.010 18

03/14/06 0.010 19

02/14/06 0.011 8

02/02/06 -0.012 9

01/20/06 -0.018 12

01/03/06 0.018 4

12/27/05 -0.010 17

12/01/05 0.010 20

11/02/05 0.010 3

10/28/05 0.014 1

10/27/05 -0.011 3

10/24/05 0.015 2

10/20/05 -0.018 1

10/19/05 0.017 1

10/18/05 -0.011 2

10/14/05 0.011 7

10/05/05 -0.013 1

10/04/05 -0.011 20

09/06/05 0.012 3

08/31/05 0.013 11

08/16/05 -0.013 27

07/08/05 0.011 10

06/23/05 -0.014 25

05/18/05 0.010 4

05/12/05 -0.011 2

05/10/05 -0.010 7

04/29/05 0.014 1

04/28/05 -0.013 5

04/21/05 0.019 1

04/20/05 -0.014 3

04/15/05 -0.014 1

04/14/05 -0.013 1

04/13/05 -0.012 3

04/08/05 -0.010 7

03/30/05 0.014 5

03/22/05 -0.010 9

03/09/05 -0.011 3

03/04/05 0.012 8

02/22/05 -0.015 11

02/04/05 0.011 12

01/19/05 -0.010 1

01/18/05 0.010 9

01/04/05 -0.012 23

12/01/04 0.011 7

11/19/04 -0.011 11

11/04/04 0.014 1

11/03/04 0.013 5

10/27/04 0.012 1

10/26/04 0.015 2

10/22/04 -0.011 11

10/07/04 -0.011 4

10/01/04 0.017 7

09/22/04 -0.013 13

09/02/04 0.011 11

08/18/04 0.010 2

08/16/04 0.010 2

08/12/04 -0.011 2

08/10/04 0.013 2

08/06/04 -0.014 1

08/05/04 -0.016 11

07/21/04 -0.018 1

07/20/04 0.013 12

07/01/04 -0.014 17

06/07/04 0.015 8

05/25/04 0.014 11

05/10/04 -0.010 1

05/07/04 -0.016 4

05/03/04 0.011 3

04/28/04 -0.013 4

04/22/04 0.014 2

04/20/04 -0.017 5

04/13/04 -0.014 10

03/29/04 0.014 2

03/25/04 0.013 3

03/22/04 -0.013 1

03/19/04 -0.014 2

03/17/04 0.011 2

03/15/04 -0.012 1

03/12/04 0.013 1