Jul

10

Happy Infections, from Kim Zussman

July 10, 2010 | Leave a Comment

I found this article on how happiness and sadness are like infectious diseases very interesting.

Anton Johnson adds:

Correlated to feline population density?

Jul

3

Vol to Vol Part 10, from Kim Zussman

July 3, 2010 | Leave a Comment

Last week SPY dropped 5.2%. Going back to 1993, ranked weekly drops by % as follows:

1: 1-2%

2: 2-3%

3: 3-4%

4: 4-5%

5: 5-6% (like last week)

6: 6-7%

7: 7-or more % (7,7,7,8,8,10,10,19)

Then checked following week's return.

The chart compares variance of next week by prior week's 1-7 ranking; another version of "the wilder it gets the wilder it gets"

Using the same ranking system, this chart compares mean returns of weeks after down weeks ranked 1-7 to the mean returns after weeks declining between 1-19%.

The mean return is positive (NS, see below), but without a monotonic relationship with size of prior week's decline.

One-Sample T: nxt wk

Test of mu = 0 vs not = 0

Variable N Mean StDev SE Mean 95% CI T P

nxt wk 242 0.0038 0.0340 0.00219 (-0.00051, 0.00811) 1.73 0.084

Jul

1

Black Cross, from Kim Zussman

July 1, 2010 | 1 Comment

The 50D moving average of SPY may soon cross below it's 200D MA. Looking for instances when this occurred, AND it was the first downward cross in at least 20 days, found 6 instances since 1993. The following 5D tests bearish, but 10D and 20D are flat:

Date 5D 10D 20D

12/28/07 -0.042 -0.041 -0.077

10/01/98 -0.022 0.072 0.107

11/02/00 -0.019 -0.037 -0.073

04/29/94 -0.008 -0.013 0.017

08/25/04 0.002 0.012 0.003

07/25/06 0.004 0.006 0.027

avg -0.014 0.000 0.001

stdev 0.017 0.042 0.069

n 6 6 6

t -1.98 0.00 0.02

Jul

1

Down First Half, from Kim Zussman

July 1, 2010 | Leave a Comment

DJIA is down about 5% this year, Jan-June. Going back to 1928, for 1st half declines between -2% and -10%, here are the next month (July), 3-month, and 6-month return means:

Jan-Jun nxt 1mo nxt 3mo nxt 6mo

avg -0.065 0.000 -0.040 -0.026

stdev 0.022 0.053 0.126 0.191

n 20 20 20 20

t -0.02 -1.42 -0.61

>>Nothing much; 3mo somewhat bearish.

Same check on 1st half declines worse than -10% tested bullish for Julys, and N. S. for 3 and 6 mo.

The 3mo following down 1Q tests significantly less than all (non-overlapping) 3 mo periods, but 1-mo and 6-mo are not different. Which is a different question than is mkt up?

July all mo

Mean 0.000 0.005

Variance 0.003 0.003

Observations 20.000 974.000

Hypothesized Mean Difference 0.000

df 20.000

t Stat -0.436

P(T<=t) one-tail 0.334

3 mo all 3mo

Mean -0.040 0.016

Variance 0.016 0.011

Observations 20.000 325.000

Hypothesized Mean Difference 0.000

df 21.000

t Stat -1.949

P(T<=t) one-tail 0.032

6 mo all 6mo

Mean -0.026 0.032

Variance 0.036 0.020

Observations 20.000 163.000

Hypothesized Mean Difference 0.000

df 22.000

t Stat -1.306

P(T<=t) one-tail 0.103

Jun

28

We Need Inflation Now, by Kim Zussman

June 28, 2010 | 1 Comment

Attached chart of TIP/TLT (Inflation-indexed bond etf / 20Y bond etf) shows recent roll-over in the wrong (deflationary) direction for those seeking easier repayment of debts and waving of flags over tracts of appreciating houses.

OTOH it is a good direction for those seeking more stimulus and associated nest-feathers.

Kim Zussman refines his views:

A friend, Sam Humbert, pointed out that TIP and TLT differ in duration (~3.7 yr vs ~20). So to better isolate on inflation, here is a chart of TIP/SHY (SHY= 1-3yr Treasury bond ETF).

The recent move for TIP/SHY is up; opposite to TIP/TLT, showing a significant yield-curve-change component is affecting the former chart. I conclude that the market is more concerned recently about inflation at a 3 year horizon.

Rocky Humbert comments:

The current inflation "breakeven" for 5 Year TIPS versus 5 Year T's is 1.56%.

The current inflation "breakeven" for 10 Year TIPS versus 10 Year T's is 1.91%.

This is the least worst measure of of "investor inflation expectations."

It's important to recognize that TIPS funds (and secondary market TIPS) have a variety of complex technical and tax nuances that make apples-to-apples comparisons with straight Treasuries difficult or misleading.

For example, a taxable buyer of seasoned TIPS who experiences deflation followed by inflation can have a strikingly different total return than a buyer of seasoned TIPS who experiences inflation followed by deflation. This path dependency does not occur in regular Treasuries.

And if one is really clever, one can try to understand the WIP etf … which is based on the DB Global ex-US Inflation Linked Index….

Al comments:

I must fight the war against my own ignorance here: What is a "seasoned" TIP?

Rocky Humbert responds:

Asking a question is not a sign of ignorance. It's a sign of wisdom.

A seasoned TIP is both a delicacy at my local steakhouse, and it's an inflation-linked bond that's been trading in the secondary market for a while. The TIP's par amount increases by a CPI factor (when the CPI is positive), and the par amount decreases by a CPI factor (when the CPI is negative).

So, for back-of-the-envelope purposes, if you invest $1mm in a particular TIP bond after it's been through a few years of inflation, and then you hold it through a few years of deflation, it's theoretically possible to lose money even if you hold it to maturity. An analogous extreme example would be if you buy a mortgage-backed security in the secondary market with a 6% coupon and a price of 108 … and the homeowner(s) unexpectedly refinance … and you suddenly get 100 back….losing 8 points.

Easan Katir pleads:

The country has had so many years, decades, of rewarding borrowers and spenders through creeping inflation. How about at least a few years for the ones who have scrimped and saved, are unleveraged and tired of paying more for everything every year for most of one's lifetime. Deflation is wonderful. Everything is on sale.

Nick White writes:

That is, of course, until you lose your job because your employers has gone bankrupt from falling prices…. ![]()

Stefan Jovanovich comments:

Neither deflation nor inflation is wonderful because both are founded in dishonesties; their prices are not set by ongoing enterprise and competition but by government clipping of the coinage, political favors and the sheriff's auction. Easan exaggerates the rewards gained by the borrowers and spenders here in the Golden State. Most of the people in California who used their houses as ATMs did so because their after-tax incomes never recovered from the dot.com bust (unless, of course, they worked for the state or the schools.) There were great frauds committed on mortgage applications and by brokers, appraisers and mortgage lenders; but those were minor costs compared to the major fraud of having the GSEs become one-way hedge funds who agreed with the people chasing housing prices that no one ever lost money buying real estate. (The frauds at the retail level would never have been possible but for the demand from Wall Street. Without the credit bubble there would never have been a housing bubble.)

How about we all try a monetary/tax system that favors neither the borrower nor the lender? Prices would still fall; they always do in competitive markets because the buyers keep their eyes out for ways to get a better deal and the sellers work hard to produce things and services better, cheaper and faster. Nick is right; what makes "deflations" ruinous is not the steady decline in nominal prices that results from constant competition but the collapse that comes from a cascade of credit defaults that reduces commerce to a race to the courthouse.

In 1930 "everybody knew" that the solution to the problem was for the government to bring back the WW I boom by spending money. Mellon tried to argue against such stimulus. He did not say that the solution was to "liquidate, liquidate, liquidate"; what he did tell Hoover was that adding government borrowings to an economy already worried about private credit risks would call the soundness of monetary system itself in question. He was right, of course; that is why Hoover never forgave him and Roosevelt literally persecuted him. Once again, Gresham wins the day; sensible advice, like hard money, is never rewarded in a modern political economy.

Jun

25

Day Vs. Night Update, by Kim Zussman

June 25, 2010 | Leave a Comment

Attached chart has equity curves for day session (open to close) and overnight (close to next open) for SPY, 2000-present.

The stock market run-up from 3/03-12/07 was primarily an "overnight" phenomenon. The 08-09 decline, as well as the borrowed recovery, accrued both day and night.

Jun

24

[When it comes to the war on terror,] we need to show the world in absolutely clear terms not only what we can do, but that we are willing to do it.

Unfortunately, there are far too many people in this country who are under the mistaken impression that [people everywhere] want the same things we want, and respond to the same set of incentives that we do, or respond to the same set of values that we do.

They don't.

Yet, we naively apply our "higher standard" to them. I almost hate to say it, but this is akin to the animal rights wacko's who actually think that they can give rights to animals. You can't give rights to anything that isn't capable of understanding them, or who is incapable of handling the responsibilities that go along with those rights…..let alone reciprocate and respect your (our) rights.

You have to deal with an animal at the level of that animal.

Laurence Glazier comments:

Is this not false logic? The mentally handicapped have rights which they may not understand. The rights of the human fetus are the subject of fierce debate. One could argue that the propensity of humans to wage war is a form of projective identification to avoid facing the moral question of the abuse of animals. Those that have resolved the latter issue in their own minds are not noted for forming battalions.

Moreover referring thus to the level of animals is unfair to animals which are less violent than humans.

In the UK animals have limited rights and there are frequent cases of conviction for cruelty to animals. Progress is slow in this area as we are still in the secondary cannibalistic era.

Jeff Watson writes:

The 9th district court in California gave Dolphins (Porpoises) the right to sue the Navy. Somehow, the rights of animals were being denied when the navy was training them to place limpet mines on ships and other tasks. Animals have rights, in fact, those rights should be extended to spirochetes, and they should be able to file a class action suit against the makers of penicillin which is the Zyklon-B of their species..Never mind service animals, the labor board ought to look into their working conditions, no pay, and hazardous duty. Equal rights for seeing eye dogs! As for slaughterhouses and eating animals, we need, as humans to go back to foraging for roots, berries, and lichens in order to protect the dignity and rights of our bovine and porcine citizens.

Kim Zussman comments:

Does it make any sense for the species at the top of the food chain to debate hunting (cultivating, slaughtering, farming, taxing, etc) its lessors?

What if we were somewhere in the middle: "Well, they ate our children again. But really, they deserved to die; in order to feed and perpetuate more successful species. And in any case the Good Book says we were put here for that purpose…"

Jeff Watson writes:

One of my favorite places to surf in the world is New Smyrna Beach, Florida. Best wave in the state, funky beach town vibe, very cool, mellow tropical paradise. It also has more shark bites than any place on the planet. It's a rather disconcerting feeling when I'm out on the water and realize that I'm not at the top of the food chain. http://tinyurl.com/49wgkf

Jun

17

Yield Curve and Stocks, from Kim Zussman

June 17, 2010 | Leave a Comment

Attached chart is 10Y-1Y (FRED, "Market yield on U.S. Treasury securities at 10-year, 1-year, constant maturity, quoted on investment basis") vs date, along with log SP500, 1982-present (weekly).

Note 3 major minima: 3/89, 8/00, 11/06

Note 3 major maxima: 7/92, 8/03, 4/10

Jun

4

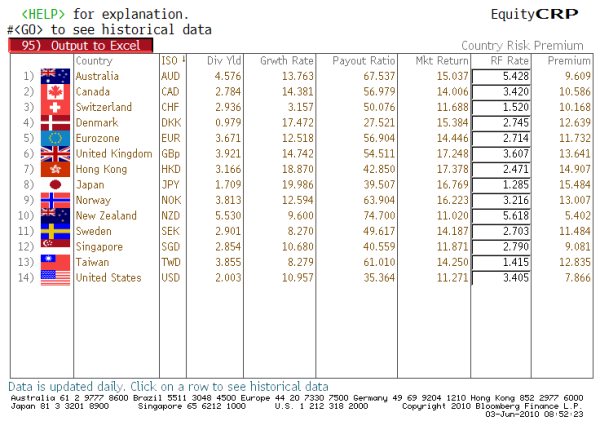

I periodically take a fresh look at the so-called "equity risk premium" for various global stock markets. There are many academic articles on this subject that are nearly useless for short-term market-timing, but quite helpful for long-term asset allocation. For example, here are two papers from a Google search on "Equity Risk Premium Across Countries":

Ibbotson, Chen: The Supply of Market Returns (2001) [30 page pdf]

or

Dimson, Marsh, Staunton: Global Evidence on the Equity Risk Premium, (2002) [17 page pdf]

What is the current situation? Examining the Bloomberg screenshot below, one notes that Japan has by-far the highest nominal risk premium. It's possible that this is due to their JGB yield at 1.28% — and if JGB yields increase by 100-200 basis points, the risk premium will decline by the same amount — reducing the apparent relative cheapness. Nonetheless, I looked at a handful of mega-cap Japanese stocks. When I plugged in a 1% growth rate and lowered the risk-premium to around 10-12%, the "theoretical" value of these stocks increased massively — in many cases predicting more than a doubling in valuation.I am NOT rushing out to blindly buy Japanese stocks, even though Toyota, Honda, Mitsubishi, UFJ, Canon, Sumitomo, Mitsui, Sony etc. model-up incredibly well on a Dividend Discount Model that assumes any positive GDP growth over the next decade.

But one wonders whether we are approaching trough valuations after a 20-year bear market? And, other than slow, trend-following technicals, what approaches would one use to make such a call?

Sushil Kedia adds:

If there is a larger risk premium in Yen terms, is it also the same in terms of Dollars?

What if Tokyo pits are pricing a much stronger Yen ahead in the year? Hungry mind is just generating possible explanations and keen to learn. With the JGB Yields being where they are for years, the real variation comes from the change in interest rates in the US treasuries. Is the Risk Premium in Japan a good way to start thinking of a theses that the interest rates in the world will be rising in other important places including the USA, later in the year?

Kim Zussman comments:

Here is log nikkei in USD. It appears US investors were less driftless than the Japanese.

Jun

4

Inspired by the Berkeley astronomers in The Education of A Speculator, below is a chart of log CPI (monthly, 1928-present, FRED) vs contemporaneous log DJIA monthly closes.

Log CPI ranged between 1.1 and 2.3 during this period. Beginning at the lower left, the downward squiggle was the depression - when CPI declined along with stocks. Then both stocks and CPI rose (irregularly) in tandem, from CPI ~1.13 to 1.5, from the 1940's to the mid 60's. CPI increased from 1.5 in 1965 to 2 in 1983 - a period which saw no net change in stocks, with log DOW stuck below 3. The great bull market 1983-2000 occurred while CPI rose from 2 to 2.2.

The last decade is depicted by the squiggles at the upper right, ending with a miniature retracement of the 1930's style cpi/stock decline followed by increase.

Jun

4

Harry Browne’s Take, from Victor Niederhoffer

June 4, 2010 | 1 Comment

Harry Browne's book about why the best laid investment plans go wrong has a very precise and useful chapter on how to evaluate forecasters starting with keeping records of the actual forecasts, when they were made what the price was, and what transpired. These are usually very different from the humble self evaluations "we erred on calling the high in silver" we said 1080 but it was 1065. A hilarious review of such is contained in edspec.

Harry Browne's book about why the best laid investment plans go wrong has a very precise and useful chapter on how to evaluate forecasters starting with keeping records of the actual forecasts, when they were made what the price was, and what transpired. These are usually very different from the humble self evaluations "we erred on calling the high in silver" we said 1080 but it was 1065. A hilarious review of such is contained in edspec.

Jeff Watson comments:

To me, the value of forecasters, pundits, touts, advisors, mavens, etc lies in the opportunity in fading them. When one says that everyone in the world should be short t bonds, I look at the other side. When a guy rides a motorcycle around Europe and says to buy German stocks and forget about them for 5 years, I take a look at the other side. When the newsletters and blogs tell you to do one thing, the move has already happened or else they're talking their book or gambling.

Kim Zussman comments:

Years ago, the late Louis Rukeyser published a newsletter which listed picks of various market experts either interviewed on Wall $treet Week or profiled in the letter. Each issue had a running return for each pick, as well as the average - which was usually very good.

I noticed once in a new issue that a stock had been dropped from the list of recommendations, with a note to the effect "manager no longer covers". Also noticed the bad return for this stock had been removed from the running total average. Had you bought all the recommendations, your results would definitely have been worse than reported!

There is a similar problem with extrapolating stock index data from over 30 years ago, before indexing was widely available / utilized. Think of how difficult it would have been to own 500 stocks of the SP500, in correct proportion, adding and deleting simultaneously with the index. This may be an "indexation premium", which ought to be gone by now.

May

21

Log Nasdaq vs Log SP500, from Kim Zussman

May 21, 2010 | Leave a Comment

The attached chart is plot of weekly closes of the Nasdaq vs corresponding (by date) log SP500; the time period is 1971 to Present.

Mostly a linear relationship (not mathematically one-to-one as there can be various log nas for a given log sp500), but note the upwardly-divergent squiggle at top right. This is the tech bubble; the overall market was doing "well" but Nasdaq was doing "great". Multiple paths in this area are various relationships with log Nasdaq during the frequent sojourns of log SP500 between 2.8-3.2, ca 1996-present.

The current point has approximate coordinates (3.0,3.3), in the upper right quadrant. Imagine an arrow "you are here".

May

19

A Bizarre Business Model, from Rocky Humbert

May 19, 2010 | 2 Comments

From the Associated Press:

From the Associated Press:

"CLAYTON, Mo. - Panera Bread Co. is asking customers at a new restaurant to pay what they want. The national bakery and restaurant chain launched a new nonprofit store here this week that has the same menu as its other 1,400 locations. But the prices are a little different — there aren't any. Customers are told to donate what they want for a meal, whether it's the full suggested price, a penny or $100. The new store in the upscale St. Louis suburb of Clayton is the first of what will Panera hopes will be many around the country. Ronald Shaich, Panera's CEO until last week, was on hand at the new bakery Monday to explain the system to customers."

PNRA is a public company. If this model actually works, what does that predict for the economy as a whole?

Kim Zussman comments:

Some museums are similar, asking patrons to make a donation at the door if they wish (Last time at NY Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Santa Barbara Museum of Art), at a recommended amount (or less/more). Presumably this is to allow poor people to enjoy the exhibits, without requiring those with means to pay.

I wondered whether they studied this, and found this kind of model to be more profitable, bringing in lower mean price but more customers. There could also be data generated on which items are most in demand, etc, useful for other stores.

Rocky Humbert replies:

Museums may not be the right model as the "recommended" admission price doesn't cover the true cost. According to Museum News, in 2004, the median entrance fee to an art museum was $7, however, the median cost to the museum for each visitor was $35.98 Museums are able to do this because of their endowments and benefactors. While you might someday visit the Rocky Humbert Memorial Wing at the MMoA, I promise that you'll never find the Rocky Humbert Bagel Wing at your local Panera's.

May

14

I will stand up and predict a retest of the Flash Crash low, making it the Ultimate Milstein.

I will stand up and predict a retest of the Flash Crash low, making it the Ultimate Milstein.

Kim Zussman adds:

Last week's events remind us that:

1. The probability of zero for a stock is not zero

2. The probability of SP00 zero is not zero but much closer to zero than #1 above

3. The probability of SP500 660 is less when it is 1100 than when it is 670, at least for time periods you care most about

May

10

Tail Drag Race, from Kim Zussman

May 10, 2010 | Leave a Comment

One check on whether declines are faster than advances is to compare the size of extremal moves over equal times. SPY c-c (93-p) daily returns were ranked top to bottom. The largest gain day was paired with the largest loss day, second largest to second largest, etc. Then took the difference between each ranked extremal gain and the absolute value of the correspondingly ranked loss, for the top 200 extremes. The effect is subtracting the decline tail from the gain tail:

G1-L1

G2-L2

G3-L3

…….

G200-L200

The attached chart plots these differences, beginning with the top ranked gain - loss (14.5%-9.9%).

At least for the 24hr time-frame, "which is bigger" is a complicated question. At the tip of the tails, extremal gains are much larger than losses. The difference rapidly declines, and goes in favor of losses at point 3. The advantage switches to gains at point 9, then oscillates above and below zero until point 29 - when gains again outsize losses all the way to point 81. From 81 on, losses are smaller than gains all the way to point 200 (which is 400 pair-differences; about 10% of the total series of 4350 days).

The contest may be different for shorter (and longer) time-frames, as seen in a certain 5 minutes yesterday. Having reformed from intra-day data this study will be left for others.

May

10

This week is a 10-week low in DJIA. Going back to 1929, checked for instances when this week's close was a 10 week low, AND it was the first 10W low in 10 weeks (a dip). Then checked the return going forward, for the next 10W, 20W, 40W, and compared the mean returns for such "dip-buying" with the means of non-overlapping periods of 10W, 20W, 40W.

(This study is not statistically (or politically) correct, as there is overlap with some of the dip-buying and the data is not strictly independent. However assuming an investor bought at all the stated points, comparison of mean return to dip buying vs buying every 10W, 20W, 40W is valid)

Here are the comparisons of mean returns to dip-buying v automatic buying:

Two-sample T for 10W ret vs all 10W

N Mean StDev SE Mean

10W ret 132 0.0108 0.0915 0.0080 T=-0.15

all 10W 425 0.0122 0.0860 0.0042

Two-sample T for 20W ret vs all 20W

N Mean StDev SE Mean

20W ret 132 0.022 0.136 0.012 T=-0.15

all 20W 212 0.024 0.121 0.0083

Two-sample T for 40W ret vs all 40W

N Mean StDev SE Mean

40W ret 132 0.039 0.190 0.017 T=-0.40

all 40W 106 0.048 0.169 0.016

All of the "buy the dips" returns were lower than equivalent auto-buy periods (though not significantly). Note also the stdev of dip buying was higher (though NS, F-tests not shown): the result of buying in declining/more volatile markets.

How could buying after declines give lower returns than buying all the time? By missing periods of high momentum (eg 1990's), when stocks go up for long periods without making many 10W lows. (From a T and A perspective, this is equivalent to missing the returns above long-term moving averages).

If profit were simple we'd all be rich.

Craig Mee comments:

British Politics in hung parliament, US struggling with oil disasters, Aussie politicians trying to bring in a 40% extra mining tax because the miners are making too much dough and should share it, (where was the government, showing gifts when gold and raw materials where going nowhere for 20 years. They want their hand in the cookie jar, after shocking mismanagement) Europe struggling and debt across the board globally, and as Vic said retail accounts coppering a hammering. No doubt anyone close to retirement who rode the last equity wave up will be thinking of any bounce, and I'm going to cash.

I'm all for contrarian trading, but as Larry has outlined once before, wait for the setup, in price, and volality (just as it did on the recent high). Wash outs no doubt provide a key guide.

May

10

Insurance Week, from Kim Zussman

May 10, 2010 | Leave a Comment

VIX closed at 40.9 Friday- doubling in 4 days to a 1-year high - after closing at a 1-year low less than a month ago on Apr 12.

Also interesting that despite relative calm Friday compared to the day before, Friday's VIX close was higher than Thursday's high (Yahoo data):

Date Open High Low Close

5/7/2010 32.8 42.2 31.7 41.0

5/6/2010 25.9 40.7 24.4 32.8

5/5/2010 26.0 27.2 23.8 24.9

5/4/2010 22.5 25.7 22.5 23.8

5/3/2010 22.4 22.4 19.6 20.2

Vince Fulco writes:

I've been thinking for some time, which solidified watching Thursday's action, that there could be parallels to mkt instability and earthquake prediction. Something along the Arias Intensity measure could be created with index members acting as observation stations. I'm doubtful the existing vol indices do the job:

The Arias Intensity (IA) is a measure of the strength of a ground motion.[1] It determines the intensity of shaking by measuring the acceleration of transient seismic waves. It has been found to be a fairly reliable parameter to describe earthquake shaking necessary to trigger landslides.[2] It was proposed by Chilean engineer Arturo Arias in 1970…

Barking up the wrong tree or some theoretical underpinnings?

Thanks…

May

7

Throwing in the Towel, from Alan Millhone

May 7, 2010 | 2 Comments

Noted in my morning's rag that Celtics GM Danny Ainge was fined $25,000 for tossing a towel to try and distract Cavalier forward J.J. Hickson as he shot a free throw! A really visible example of very poor sportsmanship. Perhaps the NYSE floor traders need to hire him to try and distract the sellers the last couple of days?

Noted in my morning's rag that Celtics GM Danny Ainge was fined $25,000 for tossing a towel to try and distract Cavalier forward J.J. Hickson as he shot a free throw! A really visible example of very poor sportsmanship. Perhaps the NYSE floor traders need to hire him to try and distract the sellers the last couple of days?

Kim Zussman replies:

The 1930s created a generation of retail investors who decided equities were fool's bets (and one could argue that the next unadulterated generation, coupled with a fortuitous lack of major wars, explains much of the bull market 1980-00).

One wonders how many broken hypotheses, market glitches, scams, sovereign/municipal defaults, real-estate which never drops, and government interventions it will take to persuade the 401Kaboomers who are starting to retire (often without choice) that assumptions about investment vehicles makes asses out of…

May

7

Speaking of Fishing, from Kim Zussman

May 7, 2010 | Leave a Comment

The range for May 6, 2010 was 1168.75 to 1056.00 on the S&P futures.

On Tue, Apr 13, 2010 at 9:05 AM, James Lackey wrote:

Would one of you big fish please buy, sell, or short the markets

please? The movement and ranges are too small. The joke around here is

day traders can't even find a way to lose money…much less make.

Dear Lack, this proves that the round trip distance to G-d is 23 light-days ( assuming v(prayer) = c )

May

5

Sell In May, from Kim Zussman

May 5, 2010 | Leave a Comment

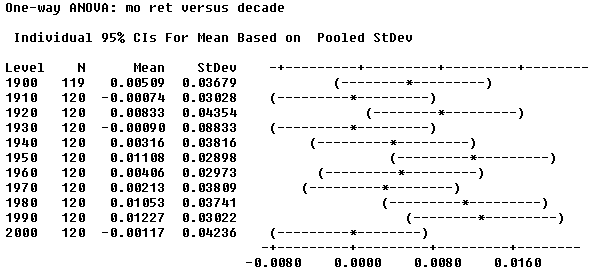

Here is a check on the evolution of "Sell in May". SP500 Nov1-Apr30 mean returns were tested against zero, by decade ("00" = 2000's, "90"'s, etc):

Test of mu = 0 vs not = 0

Variable N Mean StDev SE Mean 95% CI T P

N-A 00 10 0.0105 0.0912 0.0288 (-0.0547, 0.0757) 0.36 0.724

N-A 90 10 0.1154 0.0871 0.0275 ( 0.0531, 0.1777) 4.19 0.002

N-A 80 10 0.0830 0.1055 0.0333 ( 0.0075, 0.1585) 2.49 0.034

N-A 70 10 0.0648 0.1233 0.0390 (-0.0234, 0.1531) 1.66 0.131

N-A 60 10 0.0576 0.1246 0.0394 (-0.0314, 0.1468) 1.46 0.177

N-A 50 10 0.0790 0.0841 0.0266 ( 0.0188, 0.1392) 2.97 0.016

All positive, 3/6 decades significantly greater than zero. Here is the same test for May1-Oct31:

Test of mu = 0 vs not = 0

Variable N Mean StDev SE Mean 95% CI T P

M-O 00 10 -0.0152 0.1514 0.0478 (-0.1235, 0.0930) -0.32 0.758

M-O 90 10 0.0442 0.0657 0.0207 (-0.0027, 0.0912) 2.13 0.062

M-O 80 10 0.0429 0.0979 0.0309 (-0.0271, 0.1130) 1.39 0.199

M-O 70 10 -0.0272 0.0683 0.0216 (-0.0761, 0.0216) -1.26 0.240

M-O 60 10 -0.0064 0.0760 0.0240 (-0.0608, 0.0479) -0.27 0.794

M-O 50 10 0.0414 0.0871 0.0275 (-0.0208, 0.1038) 1.51 0.166

3/6 decades were negative (however not significantly different than zero), 3/6 were positive (only the roaring 90's significant).

Russ Sears writes:

Having heard "sell in May" for eleven years, it is time to put paper to pencil. For the S&P index,

First day, whole mnth, month, year

1.30%, ? 5 2,010

0.54%, 5.17% 5 2,009

1.70%, 1.06% 5 2,008

0.26%, 3.20% 5 2,007

-0.41%, -3.14% 5 2,006

0.46%, 2.95% 5 2,005

0.92%, 1.20% 5 2,004

-0.07%, 4.96% 5 2,003

0.88%, -0.91% 5 2,002

1.35%, 0.51% 5 2,001

1.08%, -2.22% 5 2,000

First day 9 positives, average 0.73%, worst -0.41% 2006, best 1.70% 2008, Cumm. Binomial Dist 99.4%

Whole month 7 Positives, average +1.28%, best 5.17% 2009, worst -3.14% 2006, Cumm. Binomial Dist 94.5%

No wonder this dogma seemed annoying.

May

5

The VIC and the Churn, from Kim Zussman

May 5, 2010 | 1 Comment

When ideas that seem to hold promise intuitively don't pass the acid test, you wonder whether you left something out which may have been the key, eg, X-day high, index vs individual stock, different definitions of volatility, various lags, what other markets have been doing, which prior period assumed analagous, yield curve, inflation rate, tax regime change, seasonality, etc. Eventually you are likely to find something, and maybe put on a full-Kelly trade based on it. Then, as it goes against, you wonder whether you have overfit the data, or had so many hypotheses that you fooled yourself. Or, maybe just unlucky or unsuited to gambling?

Dr. Zussman is a trader, astronomer, philosopher and periodontist from Los Angeles.

May

4

How Fares the Sage? from Phil McDonnell

May 4, 2010 | 1 Comment

He has made his investors' fortunes…

He has made his investors' fortunes…

How has Mr. Buffet actually been doing? On July 1, 1998 BRK-A was 78,000. Today it is about 115,000 per share.

That is a gain of 43% over roughly 12 years — about 2.8% per annum compounded.

Dr. McDonnell is the author of Optimal Portfolio Modeling, Wiley, 2008.

Kim Zussman writes:

Regressing the last 10 year's monthly returns for BRK-A vs SPY (with dividends, etc), BRK-A's alpha is positive but not significant:

Coefficients Standard Error t Stat P-value

Intercept 0.008 0.005 1.583 0.116

Slope 0.436 0.106 4.113 0.000

However slope (beta) is 0.44, so you could say BRK-A out-gained SPY with less market exposure.

Rocky Humbert comments:

Math is fun. BRK-A has outperformed AAPL!

Total compounded returns (dividends reinvested) since 12/31/87:

BRK-A 18.2%

GE 10.4%

AAPL 15.5%

MSFT 22.7%

SPX 9.66%

And this is all-the-more-remarkable when one considers that AAPL returned 123% over the past 12 months.

As I said, "math is fun."

Rocky Humbert, quantitative analyst, speculator and master chef, blogs as OneHonestMan.

May

3

DJIA weekly returns (1928-p) were used to look for runs of consecutive up-weeks, such as the recent run of 8 consecutive (ending week before last). As a check on whether longer up-runs end in bigger declines, regressed the run-terminating down week return (the week ending the up-run) against the count of consecutive-ups ended:

Regression Analysis: week ret versus run up wk

The regression equation is week ret = - 0.0155 + 0.000405 run up week

Predictor Coef SE Coef T P

Constant -0.015497 0.001188 -13.04 0.000

run up wk 0.000405 0.000319 1.27 0.204

S = 0.0131489 R-Sq = 0.3% R-Sq(adj) = 0.1%

Conclusion: No significant correlation between run-terminating decline and length of up-run.

The attached chart compares means of run-terminating decline weeks, by length of prior up-run. As with the regression, there are no obvious differences between run-ending decline week returns as a function of run length. (If any of the decline means differed significantly from the global mean, it would be beyond the red confidence interval limit-lines. The lines diverge as run-length increases because there are fewer long runs than short ones).

May

2

For the First Time, from Victor Niederhoffer

May 2, 2010 | Leave a Comment

For the first time since October 2006 there were no declines of 1% or more in the month of March 2010. One hypothesizes that the number of such declines will increase from the three in April 2010. Indeed, one hypothesizes that a month with zero such declines like March 2010 is inordinately associated with the end of a bull market in Birinyian terms – assuming such exist.

For the first time since October 2006 there were no declines of 1% or more in the month of March 2010. One hypothesizes that the number of such declines will increase from the three in April 2010. Indeed, one hypothesizes that a month with zero such declines like March 2010 is inordinately associated with the end of a bull market in Birinyian terms – assuming such exist.

Kim Zussman writes:

To clarify, these dates are for 21D periods which had one or more daily decline <-1% and were following a 21D period which had no declines <-1% (like March and April 2010). The first column after "Date" is count of declines <-1% in that period. Next col is that 21D period return. 3rd column is count of declines <-1% in the next 21D period, and the last column is the return for the next 21D period.

The last 4/5 mean returns for subsequent 21D periods have been negative:

Date count -1% 21d ret nxt 21-1% nxt21 ret

05/31/07 1 0.030 4 -0.018

01/30/07 1 0.001 1 -0.018

11/27/06 1 -0.005 0 0.032

04/28/06 1 0.006 4 -0.039

01/27/06 1 0.022 1 -0.002

10/26/05 3 -0.020 1 0.065

08/26/05 1 -0.031 0 0.009

11/26/04 1 0.051 1 0.026

07/29/04 2 -0.031 3 0.007

03/29/04 5 -0.020 3 0.000

01/28/04 1 0.030 0 0.015

Apr

23

Getting Even, from Kim Zussman

April 23, 2010 | Leave a Comment

Time once again to see what % gain needed to get to even after X% loss:

% gain needed

% loss back to even

-10 11

-15 18

-20 25

-25 33

-30 43

-35 54

-40 67

-45 82

-50 100

-55 122

-60 150

-65 186

-70 233

-75 300

-80 400

-85 567

-90 900

-95 1900

-100 Robert Mugabe

Apr

16

Types of People Who Disseminate Views About The Market, by Victor Niederhoffer

April 16, 2010 | 17 Comments

What are the many types of people who disseminate their views about the market?

What are the many types of people who disseminate their views about the market?

There's the tout, the man who has a position and wants you to get into it so that it will move in his favor. There's the sponsor, the man who advertises or sponsors a program who is always treated well by that program. There's the would be manager, the personage without funds who wishes to impress you with his knowledge and ideas so that you will put money up with him. There's the old lion, the man who no longer is virile and is fighting back any young men who might take his place in the world of power or romance. There's the curmudgeon, the old man who hates everything modern, doesn't own a CD or computer and sees no reason for it, and wants to bring everyone back to the old days without technology. There's the spankist, the woman who's beautiful and always looks like she is so aggrieved with the pubic or her guest that she would have to give him a good spanking unless he puts his things in order. There's the iconoclast, the person who's always contrary and never reads the papers or travels to New York, and always feels the market is wrong.

There's the man with a hole in his shoes who's so down home that he only drinks coke and eats hamburgers and never pays a fee more than 10% of the going rate to the brokers. There's the sanctimonious, the one who pretends to be the most honest person in the world– who won't under any conditions tolerate a blemish in the reputation of his firm even if it costs him a good stake. He's the one who never hears or is briefed about the dishonesty in his troops and finds that any allegations of misdoing in his firm that are brought to his attention never pointed directly in writing to the crime. There's the academic, the man looking for a consultancy who can manipulate numbers especially retrospective files that are very suggestive of alluring profits that a wealthy investor might wish to participate in with him. There's the mystic, the person who looks at the stars and the bent keys. There's the old timer, the person that looks at the iron castings reports and freight car loadings and newsprint figures for guidance as to where the economy is going. There is the fund manager, the man who will always be quoted on a given stock that he owns which he feels is a good buy still but which he sold the bulk of his holdings of in the quarter before the recall.

There's the jack of all trades, the personage who will explain the market going up as due to a good economic report or falling interest rates or who will explain the decline as due to uncertainty about earnings or fears of interest rate rises. There's the chronic bear, the person who never since 1966 has written a column that did not find the weight of evidence highly bearish with signs of excess in many quarters and regrettably some signs of optimism still persisting. There's the humanitarian, the person who believes that the world is very selfish and that the solution is to force everyone into doing good by redistribution or service. This personage also believes that the only good people are the poor and that the purpose of life is to make sure that any pockets of poor are stamped out regardless of how it's taken or from whom. Of course, many of these personages fall into more than one of these categories and they are mobile as their age and wealth changes. What are the major categories that I am missing or what is a better way to classify and make this useful?

John Lamberg comments:

And the mark, who in a hushed tone, glazed eyes, and a glance around the room as if someone was eavesdropping, reveals the privileged information that will make him a rich man. And the friend who, seeing the tells, suggests to deaf ears to exit before his pocket book is emptied…

Ken Drees writes:

Permabull type–always likes the market anywhere, anytime. Wears high fashion suits, well coiffed–male or female. Strong BUY! spouse/lover/significant other–why didn't you buy that, hun? Why won't you get back into this one, dear. I read about that in the paper–are we in that? Foreign fund guy–always likes an exotic market somewhere over there in that far off place. Always a better value there. Always more room for catch-up to other valuations.

Nick White writes:

With precious few exceptions, doubtless one can point to many of the most eminent bank of Sweden prize laureates…they most often get trotted out as permission to allow others to do the thinking.

Kim Zussman adds:

Don't forget the Walter Mittyist.

Market hobbyist with secret hopes to surprise to the upside. Knows a little about a lot, but nothing in depth. He dangerously equipped with the same software and data filtered hourly by everyone in the 100 million Mitty-march.

Known to recognize causal patterns everywhere, convinced they are invisible to others. A market philanderer, he migrates wounded from one instrument to the next, and from one seductive strategy to another. Momentum - reversion - correlation - divergence.

Mitty envies his brother, Admitty, who worked for the city and retired at 50 with 90% pay.

Apr

14

Happiness and Certainty, from Kim Zussman

April 14, 2010 | Leave a Comment

Assuming the majority hold stocks long, happiness is associated with a large rise, and unhappiness with a large decline. Independently of happiness, uncertainty can be thought of as volatility; for example, intra-day range.

SPY 93-present was checked for daily return/happiness as well as range/uncertainty, defined as:

(H-L) / {(H+L)/2}

Uncertain days were defined as those with range >3% (V). Happy days were up >2% (U), and unhappy ones down more than -2% (D).

With these assumptions let's see whether uncertainty presages uncertainty or unhappiness. First, compare returns "r" after high-uncertainty days which were either happy or unhappy:

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances

VUr VDr

Mean 0.0007 0.0045

Variance 0.0004 0.0011

Observations 70 99

Hypothesized Mean Difference 0

df 165.0000

t Stat -0.9313

P(T<=t) one-tail 0.1765

Uncertain days which were either happy or unhappy were both followed by up days on average, though the difference was NS (due to higher variance after down days).

Next see what happens to uncertainty after uncertain days which were either happy or unhappy:

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances

VUv VDv

Mean 0.0303 0.0421

Variance 0.0003 0.0007

Observations 70.0 99.0

Hypothesized Mean Difference 0.0

df 166.0000

t Stat -3.6144

P(T<=t) one-tail 0.0002

After uncertain days, uncertainty after happy days (up) was significantly lower than after unhappy days (down).

When uncertainty is high, market participants become more uncertain when they are unhappy.

Apr

10

Tiger’s Comeback, from Kim Zussman

April 10, 2010 | Leave a Comment

DJIA daily returns (1929-present) were partitioned into non-overlapping 50 day periods. For each period, counted number of days with return greater than 0 (up days). For the recent 50D period ended Friday, there were 33 up-days (66%), which is in the highest 3.6% count of 50D>0 for the series.

The attached chart shows 50D>0 counts for the entire period, and the stem-leaf below covers the tree aspect:

To clarify the stem-leaf, the rows tally (using the "ones" digits) the number of each 50D up-count. The second column of each row is the "tens", the first column is count for that row and all those larger, and each number to the right of tens row represents an individual count.

eg, for the bottom row: 5 3 44455

3 is the tens, and 4445 are ones. Thus there are five observations in this row: 34, 34, 34, 35, 35 (and they are the top 5 observations in the sample).

The row above the bottom counts: 10 X 32's, and 9 X 33's. "24" before this row says there are 19 in this row + 5 larger (in the next row).

Perhaps the ranking is clearer in the following histogram for the same data, with a marker ("o") above the current "33" count.

But wait…there's more!

The probability chart below incorporates a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality for "count of up days within 50D periods". The P-value is N.S., and as shown in the graph, the [statistically non-significant] deviation from normality is due to "heavy tails" (too many high and low counts).

Apr

8

P&C Insurance Companies, from Bill Rafter

April 8, 2010 | Leave a Comment

Suddenly my "buy" list has a large number of companies which have never graced the list before. They are property and casualty insurers. Although they have sufficient capitalization, their volumes are too small for me to get involved. Does anyone know why they would be in favor?

Dan Grossman writes:

Volumes too small for you to get involved… You must be quite a heavy hitter, trading millions of shares.

Volumes too small for you to get involved… You must be quite a heavy hitter, trading millions of shares.

I don't know what you mean by in favor, but because the insurance companies held mostly bonds, including mortgage bonds no one knew the value of, they were beaten down to very low levels, below book value, PE multiples of four or five. Now bond valuations are normalizing, and I guess the insurance stocks are returning to reasonable levels.

Scott Brooks writes:

I deal a bit in the insurance world and I have to say that this baffles me. Insurance brokerage firms that I deal with are hurting big time. Premiums are down as small businesses (which insurance brokerage firms have as clients) continue to layoff, not hire, and generally decrease payroll.

Maybe their revenues are down, but their margins are looking better, but I find that hard to believe since every P&C guy I know is busting his butt to bring on as many new clients as possible and bidding as low as possible to "buy" the business. The problem is that their competitors are doing the same to them.

Vince Fulco comments:

A few I follow remain at a healthy discount to book value (WTM, CNA) and I've been wondering when the rising tide would lift these ships– since other industries are being given the benefit of the doubt that conditions are normalizing — and when would some of them get credit for adequate portfolio management and improving pricing and underwriting activity. Loosely speaking, a properly running P&C company can trade from .9-1.3x book and when the punch bowl really overflows, multiples of 1.5-1.8x are possible. Still plenty of room vs. normalized valuations. Why it has taken the crowd until now to really start bidding them up, I remain puzzled particularly vs. underlying corporate performance. It would seem the investors wanted to wait the half life of the bond portfolios to ensure no more problems as most run short duration portfolios.

Secondarily, there had been concerns within the industry about six months back that the Obama administration would go after the Bermuda-domiciled ones doing biz in the US for a bigger tax bite. That seems to have fallen by the wayside for now. Talking my book as I've owned WTM off and on for the last seven years.

Ken Drees adds:

The big question is since these insurance companies were screwed by their debt holdings, took writeoffs and have muddled through — some with Tarp but most P&C did not get Tarp — where do these companies park their cash now? They used to make money in the derivative leverage through the bond kingdom — outside of normal operational gains through underwriting. What is the risk of their holdings now? I don't see many stock buy backs from these guys and I don't see dividend rates that have gone up — both factors here would show that companies would rather pay out earnings or reinvest in themselves. Will they be able to ring the registers as normal through the bond markets?

Kim Zussman replies:

At a recent lecture by a business law attorney, the take-away message was "everyone needs business practices liability insurance." He went through a litany of litigations; violations of overtime laws, rest-breaks, bonuses not being factored into overtime calculations, performance reviews, extensive paper-trailing, s_xual harassment (including a married doctor who had relations with a woman six times before hiring her, then continuing to pursue her on the job).

In an environment of increasing regulation/litigation, empowerment of little old ladies in lieu of rich guys, and increasing taxes, the deductible expense of increasing insurance coverage could make sense — even though lining pockets of bureaucrats and their legal co-conspirators.

Phil McDonnell asks:

Vince, I have a question. For CNA the ratio of receivables to revenue is about 100%, for wtm it is about 75% (by eye). That would correspond to 12 and 9 months worth of receivables they are owed by their customers. Are their customers really the slowest payers in the world or am I missing something?

Dr. McDonnell is the author of Optimal Portfolio Modeling, Wiley, 2008

Vince Fulco responds:

Not sure where you are looking but the largest receivables on the balance sheet from the last few years relates to business they've reinsured with others. WTM management is generally more risk averse than their peers and is inclined to cede segments of their business to better define their upside/downside. These arrangements have truing up terms, conditions and times which make the receivables ratio more lumpy than an ordinary industrial concern. The mix of biz between them and CNA is probably another factor.

If you are speaking specifically to 'insurance and reinsurance premiums receivable', they've been 21-22ish% of revenues for the last few years. I have no specific answer for that but it doesn't seem out of line if we think of the balance sheet as a point in time.

Apr

6

Briefly Speaking, from Victor Niederhoffer

April 6, 2010 | 7 Comments

One has always hypothesized that holidays are inordinately associated with major turning points. One hypothesizes that the correlation between the extent of bailout and subsequent economic recovery between countries is not zero. One notes the story from The Book of 5 Rings where a group of wealthy samurai were traveling in Kyoto and were met by a vanguard of vassals telling them that a group of noblemen were behind them and they should bow down on floor in prostration. It turned out the noblemen were robbers and stripped them of their clothes and honor and the samurai had no recourse but to renounce their profession out of shame. What lessons does this have for markets, market people, and others? One believes that the early leads in basketball games and other games tend to be increased in subsequent parts of the game. One hypothesizes that the expected change from the time that the NBER announces that a recession is over or started are opposite in direction from the economy's current announced state — i.e., after they announce a recession the market goes up more than after they announce an expansion.

One has always hypothesized that holidays are inordinately associated with major turning points. One hypothesizes that the correlation between the extent of bailout and subsequent economic recovery between countries is not zero. One notes the story from The Book of 5 Rings where a group of wealthy samurai were traveling in Kyoto and were met by a vanguard of vassals telling them that a group of noblemen were behind them and they should bow down on floor in prostration. It turned out the noblemen were robbers and stripped them of their clothes and honor and the samurai had no recourse but to renounce their profession out of shame. What lessons does this have for markets, market people, and others? One believes that the early leads in basketball games and other games tend to be increased in subsequent parts of the game. One hypothesizes that the expected change from the time that the NBER announces that a recession is over or started are opposite in direction from the economy's current announced state — i.e., after they announce a recession the market goes up more than after they announce an expansion.

Rocky Humbert writes:

The continuous surfeit of negativity over the past year (and now hints of protectionism) makes one ponder whether one fell asleep during the housing bubble and awoke in Bizarro World (the mirror-image of Superman's world)… A successful investor doesn't need to either celebrate unemployment (Dr. Rehmke) nor declare millions are out of work forever (Dr. Dreyfus). Both statements are simply provocative– it's much less dramatic to simply observe that employment is a lagging indicator. (Yawn.) Perhaps it would be good medicine for all– if the Chair resumed his slights toward Alan Abelson (last mention July 20, 2007), and prior to that more than once/month. Most importantly, for those who are looking for a "major turning point," I share the words of Bruce Kovner, with whom I had the honor of briefly working: "Listen to the market."

Put simply: for the past year, the optimists saw a monetary/fiscal cyclical recovery with the yield curve predicting growth and inflation. During the same time, the pessimists saw a false stimulus/inventory uptick with the yield curve predicting troubling deficit/supply overhang. (No one expects the job market to recover meaningfully before 2011+.)

By any standard, the pessimists have been horribly wrong. But instead of acknowledging that things are improving, they are being Alan Abelsons, digging in their heels, and predicting that the next huge downturn is just around the corner.

Pitt T. Maner III comments:

Trying to be more in the optimistic camp it looks like the US unemployment fits a hysteresis model. Sort of like TW at Augusta and at home–it could take awhile and that's if there are no more more shocks along the way! :

1. According to Caporale and Alana , two well-known facts about the unemployment rate are

(i) the high persistence of shocks, or hysteresis (see Blanchard and Summers, 1987), which is a feature, among others, of "insider" models (see Lindbeck and Snower, 1988), or of models in which fixed and sunk costs make current unemployment a function of past labour demand (see Cross, 1994, 1995), and

(ii) its asymmetric behaviour, namely the fact that unemployment appears to rise faster in recessions than it falls during recoveries.

2. The next survey of Professional Forecasters will be May 14th, but most see an improving jobs situation. Slow at first but accelerating by end of current POTUS term.

3. Interesting chart of GDP fall vs. unemployment rise (Okun ratio). Less regulations in US (and Canada) would seem to be a long term positive, but the US and Canada sensitivities to GDP fall are higher because workers can be let go faster.

Kim Zussman adds:

Here is an update on P/E type-forecast, with a caveat about markets remaining irrational…if they feel like it.

Pitt T. Maner III comments:

What about the case where you may be moving quickly from high P/Es to lower estimated 12-month forward P/Es? (i.e. S&P 500 going from 31 one year ago to 23 now to possible 15 in 12 months time). So if you have a high rate of change in the P/E downward (if numerators continue to grow) that might make the positive portion of the bars more likely?

It seems with the P/E in the 15-17 range you have more variability in range of returns but the forward dividend yield would still indicate lower returns given yield of 3.4 (one year ago) to about 1.8 today.

Jordan Low replies:

I think that the 10 year data mines the worst case as it includes both the dotcom and subprime busts. The peak of the dotcom was almost exactly 10 years ago, and investors in 2000 weren't looking for E. (They preferred g.)

I understand that the long window is supposed to average the business cycle. Well then, the window should be variable. As of right now, we are getting bad earnings from two crashes and many of those companies don't exist anymore. Perhaps it says something about the unfortunate timing of two bad periods and growth of the Internet being captured by late comers (e.g. Google and Facebook) rather than early adopters (AOL and Yahoo). Being an investor in today's market, not yesterday's, may still be attractive.

Apr

6

Corporate Bond Spread and VIX, from Kim Zussman

April 6, 2010 | Leave a Comment

Using Fed data, I calculated corp bond spreads: BAA yield - 10Y treasuries, weekly from 1990. (Data = "Market yield on U.S. Treasury securities at 10-year constant maturity, quoted on investment basis", "MOODY'S YIELD ON SEASONED CORPORATE BONDS - ALL INDUSTRIES, BAA").

The graph shows fairly close correlation with VIX, with the eyeball suggesting closer correlation since 9/11/01. Verified by correlation post and pre 911:

correlation

pre 9/11: 0.038

post 9/11: 0.218

David Aronson comments:

John Wolberg and I have done some work to derive a normalized version on VIX in order to produce a more accurate timing signal. However we only used various measured derived from price data as normalizing variables (price velocity, acceleration and volatility). We were able to obtain some improvement. However it appears that including the default spread might improve things even more. Anyone interested in a copy of the paper email me, aronson[at]mindspring[dot]com.

Apr

6

Canada’s Grim Future, from Stefan Jovanovich

April 6, 2010 | 1 Comment

Our daughter Eddy who is in medical school thinks the predictions of ever increasing medical costs — like David Dodge's – fail to take into account two likely changes:

Our daughter Eddy who is in medical school thinks the predictions of ever increasing medical costs — like David Dodge's – fail to take into account two likely changes:

(1) the breaking down of the medical cartel's current structure of required licenses and

(2) further advances in medical micro technology, both in drugs and in physical surgeries.

A nurse-practitioner with access to computer tools can now do as good a job of diagnosing patients as any Internist; and, just as many patients who once would have been candidates for open-heart surgery are now treated by angioplasty, so will other now expensive surgeries give way to cheaper, less invasive procedures. The medical future may not be as expensive as is feared.

If Christie's catalogs are any indicator, the really good stuff among collectibles seems destined to continue its century-long ascent to the financial heavens. Assuming that the non-profitistas and the life insurers keep the envy-the-dead tax in place, that trend seems destined to continue. However, other, less genuinely precious objects may find themselves becoming less pricy even as currencies become rivals to replace the Yugo (fiat joke!).

That seems to be happening now in our the niche of the economic environment with equipment rentals. In this part of the pond even the biggest fish are finding it hard to eat. Volvo Rents, which is at the top of the food chain, is now offering a $15,000 fee to "the referrers of franchise candidates who become Volvo Rents franchisees and open a store". Coke and ore contract prices out of Australia have certainly proven George right about the worth of tangible vs. paper assets, but there are few, if any, new takers for backhoes and the other stuff actually made out of iron and steel.

George Parkanyi writes:

I don't know what the answers are either– it doesn't look very promising given the social, political, and economic status quo– none of which can be easily changed from the inside, if at all. If you want to play the decline both here and elsewhere, I think you have to look at the eventual effect of these unsolvable problems. Governments are not only bankrupt financially, but also for ideas and simply just in the ability to execute. The knee-jerk response to each crisis du-jour is and will be to borrow and spend out of it. When they can no longer borrow, they'll just print. This can only mean continuous and accelerating currency debasement around the world, so I think tangible (vs paper) assets will remain a very persistent investment theme. Governments are going to default, and currencies are going to fail with new ones issued in their place. It's just a question of which ones and when. In that environment tangible assets (the more liquid the better) would have to do well I would think– precious metals, commodities, real estate, perhaps some collectibles, and equities that represent these things. It's not going to happen overnight, and no given trade will be a slam-dunk, but that's where I think the heart of the drift will remain.

Ken Drees comments:

5 years ago the highways were choked with landscaper trucks and their stuffed trailers with ubiquitous mowers, weed whippers and gas cans. Getting gasoline in the morning on the way to work, one would always see a few landscapers fueling up the tanks and the cans for the day.

I am lucky to see one landscaper a day now. There are many pieces of equipment for sale now–if things don't pick up this summer, you should see these items go for 20 cents on the dollar (used of course) in the fall.

Justa Guy respectfully disagrees:

Many of you do not know me, but I am a physician who has practiced in both Canada as well as in the US. In my opinion there are two issues that are a threat to health care in both the US, as well as in Canada, as follows:

(i) Increasing technology. Over the two decades that I have been practicing medicine there have been innumerable new gadgets which have allowed physicians to more precisely define where problems exist ( we used to diagnose stroke with CT scans, then it was MRI, then it was supersensitive 3 Tessla MRI, now there are some unbelievably sensitive 15 Tessla MRI machines being produced). These incremental advances in technology of course come with increasing costs. Unfortunately these advances rarely improve either clinical outcome, or survival. For reasons of medicolegal protectionism, and customer expectation, we are in a culture in which the biggest, best and latest technology is the norm in our healthcare, however the use of these technologies does nothing to affect the outcome of patients.

(ii) Unreasonable expectations. There are two facts in healthcare which are undenyable: Every one of us will die, and we spend >60% of total healthcare expenditure on people within the last month of their lives. In order to curb healthcare expenditure, we must begin to recognise futile situations, and limit the resources spent in these situations. Do not beleive that is the same as Palins "death panels", rather it is a first step in healthcare fiscal responsibility.

(iii) There is a need to transition to more mid level providers as a means of primary health care delivery. Those midlevel providers will be equipped with algorithms for how to treat certain conditions in a medically proven and fiscally responsible manner. Only if those initial steps are unsuccessful will patients be seen by internists and then specialists.

(iv) About 30% of health care spending occurs under catastrophic circumstances. These include bone marrow or solid organ transplants, trauma and accidents. In many of these circumstances, the chances of survival are minimal at best. In the US ( and to a lesser extent) in the Canadian systems, there is no good mechanism by which to limit care in such catastrophic circumstances. A poignant personal example: Several years ago, my aunt (age 70) who lived in the UK was diagnosed with an incurable ultimately fatal lung disease; her physicians told her ( with out presenting options) that her care would be designed to minimize symptoms and discomfort. She died about 2 years later. Around the same time, I was involved in the care of a wealthy businessman age 75 with the same diagnosis in the US. He was offered and ultimately received a lung transplant (even though outcomes are poor for lung transplants in patients with that condition). He died within the year. We need to learn that no matter what insurance company is paying for such cases, it is financially irresponsible to offer such extraordinary care in hopeless situations

(v) The way physicians are compensated needs to change. In most health care settings, Physicians are paid in the same way that lawyers are: the more they do, the more money they make. Example, a cardiac surgeon who does five bypass surgeries in a week makes more that the cardiac surgeon who does three bypasses, and puts two patients on aspirin rather than operating. That system of having a disincentive for choosing cheaper care is dangerous and expensive. Example: many obstetricians believe that the optimum C section rate is between 5-10% of births. In the 60's in the US it approached that number. By 2007 the rate was >30% of live births, although it remains unclear why the rates have grown so remarkably. If physicians were paid by salary, any potential for conflict of interest is removed.

In my humble opinion, without addressing these issues health care costs will continue to rise, and as David Dodge succinctly puts it, heath care will bankrupt which ever countries fail to tackle the issues.

Kim Zussman responds to Dr. Guy:

Dr Guy:

As markets amply demonstrate, there are many discontinuities and irresolvable problems inherent to the human condition. eg, be kind to animals while eating them, love thy neighbor while profiting at other's expense, woman should be faithful but with men its optional, government for the people and for the government, ration health care to others but not your loved ones.

I would likely pay for a lung transplant for one of my daughters, if there was some hope the operation could save her. And if the insurance company making billions will pay some of this, I'll take it.

Outcome, "evidence based treatment", should always be the driver but ultimately humans are driving. Doctors may earn more (earn) by doing more, Kaiser and other HMO's get to keep more by doing less. Both systems have moral hazard problems, as do all the in-between solutions brokered by governments.

Stefan Jovanovich replies:

Eddy has the fortune/misfortune to have Dr. Zussman's head for statistics. It is a blessing to have that knowledge, but it can be a curse once people in research labs discover that they have someone can actually make sense of the data Pearl Diver spits up AND, if she can't do it herself, she knows some really bright people from Cal who work at JPL who can make sense of the outputs. As a result, in her fledgling career, she has already done a full year and more of full-time lab work collating price and outcomes data for both an ophthalmology and an orthopedics lab. From that limited and completely skewed base of knowledge, she has come to these tentative conclusions about medical costs:

(1) price competition works - in those areas of care that are open to active price competition (Lasik, elective plastic surgeries), where the patients pay for at least half the ultimate bill, prices have gone DOWN each year, not UP,

(2) universal insurance is absolutely the worst possible financial model to use for financing general health care- "imagine an energy/transportation system where people were issued monthly, fixed-price gasoline insurance cards; even the most responsible, self-reliant people would find themselves thinking why not take a Sunday drive, it's free and the energy producers do everything they could to abandon market pricing and go to a cost-plus, government contracting model just as the hospitals have",

(3) the Big Lie in medicine is that there is no scarcity of skills, that, if we can only get the costs down, there are enough skilled people like Dr. Guy available to treat all the patients who need care. The rationing that the medical education system imposes does not help; but, even if the libertarian dream of open, unlicensed competition arrived tomorrow, there would still be a shortage of first-rate care. That is a truth that no one can profit from telling. On the issue of lung transplants, Eddy and her Dad are hopelessly biased; her uncle, my brother, had both lungs switched out 6 years ago so our family interest would outweigh our principles even if we believed in rationing by medico-political authority rather than price.

Apr

4

The Bull Move, from Victor Niederhoffer

April 4, 2010 | Leave a Comment

The bull move by many measures is the greatest in history. Birinyi looks for big 10% turning points in markets and found that by some measures this one is the greatest in history going up 1/5 of a % a day versus 1/6 % a day in the 10 others of comparable rise to this. And we're right in the midst of another such surge with exactly 20 days of consecutive 4% or more moves, an event that's only occured 6 times in last 15 years, with previous dates 5/28/1997, 4/06/1998, 11/24/1998, 4/12/2000, 5/15/2001, and 1/27/2004.

The bull move by many measures is the greatest in history. Birinyi looks for big 10% turning points in markets and found that by some measures this one is the greatest in history going up 1/5 of a % a day versus 1/6 % a day in the 10 others of comparable rise to this. And we're right in the midst of another such surge with exactly 20 days of consecutive 4% or more moves, an event that's only occured 6 times in last 15 years, with previous dates 5/28/1997, 4/06/1998, 11/24/1998, 4/12/2000, 5/15/2001, and 1/27/2004.

One notes also that we haven't had a a month minimum since Feb 8th, 2010. Since Feb 8, 2010, the median S&P 500 stocks is up 13%, and the top 10 are each up more than 40%. An opposite scenario is working itself out in the world of fixed income. How can we make sense of what is happening?

To what should we turn in conjunction with the bearish feedbak that counting gives. I have been considering the fields of economics, martial arts or romance. What fields would you suggest?

Vince Fulco comments:

The thought of a pendulum with too much transitory force being applied to one side comes to mind.

Russ Sears writes:

In my opinion to understand the crisis and the resulting recovery, you must understand that most of the crash stemmed from "model risks". People had bought these wonderfully complex AAA structured products that suddenly you had to be able to model the expected losses. In the past this was considered only a remote possibility with no need to model. Once it became clear that much of this "structure" was mush, it was equally clear that these things really could not be modeled well. A slight change of the breeze from the butterfly caused wild swings in the heavens.

Models with even a slight downward trend in the housing markets quickly turned into a death spiral in housing. AAA suddenly were worth pennies. And those that bought them were those least able to absorb the losses or downgrades, further cascading the price due to illiquidity.

One must wonder if this recent reversal similarly has the "all clear" signal being given, and people are coming out of their bunkers to see some rays of sun. In other words which came first for the pendulum, the crash or the recovery?

Ken Drees writes:

Some recent puffy white contrary clouds that have passed my eyes:

advertising aimed at gold straddles

advertising oil calls and bull spreads

themes of money market money needing to go to stock market to earn advertising mailers about apple type clone micro caps–a ground floor opportunity advertising for homeowners to lock in natural gas now–don't wait for summer since rates NG rates can't go lower best 12 months in recent stock market history and the recovery isn't even rolling yet at full steam.

Bond bears are simply frothy–they can't wait to feed! The fed is in a box and its locked and its under water.

Lots of interesting hooks in the water in many markets. I am not surprised since trends have been running themselves quite far without pause, and thats the action that creates the hooks–the unarguable facts of self reinforcing trend. Voila!

Kim Zussman suggests we look at the big picture:

The attached plots log [base 10] (SP500 close) every March from 1871-2010, using data from Prof. Shiller's website.

In the context of history, the recent decline and bounce don't really stand out. However stock returns of the recent decade are noticeably different than the prior two, and rather resemble the pre-WWII period.

Next, Kim Zussman looks through a magnifying glass:

Using Shiller's SP500 monthly data, here is comparison of mean monthly returns by decade 1900-2000

Note that the 2000 decade was one of only 3 (1910, 1930) with negative mean monthly returns. The two prior decades, 1980's and 1990's, both had the largest mean monthly return since the 1950's, and the 50's, 80's, and 90's - the top 3 - all occurred in the last half of the century.

I also plotted log(sp500) within each decade. Drift is noticeable in some of the decades, and noticeably absent in others.

Apr

3

Marionette Cat Bounce, from Kim Zussman

April 3, 2010 | Leave a Comment

The quarter just ended gained 7.4% in the DJIA, after two prior qtr which gained 15% and 11%. Long ago (March 2009) there was a down quarter. Looked for other instances with quarterly return pattern DUUU, also stipulating that the up-qtrs gained more than 5%. Here are the dates, along with the return for the following quarter:

Date DUUUX qtr

06/01/99 -0.058

09/01/95 0.068

03/01/83 0.081

03/01/71 -0.015

06/01/54 0.081

12/01/38 -0.146

12/02/35 0.085

avg 0.014

stdev 0.090

t 0.408

As a wakeful friend pointed out, we are now up 4 consecutive quarters after the down Q1 2009(or DUUUU). Here are the subsequent qtr assuming all 4 were up >4%:

Date DUUUUX

09/01/87 -0.253

03/02/36 0.009

06/01/83 0.009

12/01/95 0.092

09/01/54 0.122

avg -0.004

Mar

31

A Poem, from Russ Sears

March 31, 2010 | Leave a Comment

Schlock

The help laughs behind their backs,

As the Mercedes, Lincoln and Catties.

First fill the handicap spots..

Until the whole lot is full

Of Gray and Bald headed Early-Birds.

They stroll, walk and hobble,

To the supper special for the day:

Desserts puffed with air

And weak artificial flavor

Vegetables steamed to oblivion;

With variety of syrupy fruits;

All with slabs of meat

Served with pomp and detached jazz

The waiters know them by name

And the story behind each one

A doctor, a lawyer, a professor or two

Little did they know,

The devil's trade they daily made

Those toiling years ago.

To miss the daily diligence of running, hiking or seeking:

The wild beauty of the bobcat,

Attacking the spotted doe.

They would be left with black velvet deer

And serene glowing trails on canvas.

As their arteries clogged

As their blood turned to medicated sludge.

But then the conversation turns sadder

As they talk of greater minds, lovers or brothers;

Gone or in the home,

From dementia, strokes or fatty cancers.

The devil smiles as they say grace,

And thankfully say they are the lucky ones.

Rocky Humbert comments:

The studies which I've seen suggest that running 30 minutes a day will add 3.5 to 3.7 years to one's life. However, if one is awake only 16 hours/day, then that 30 minutes of running consumes 3% of one's life for an increase of life expectancy of approximately 4.7%. While this gives no value to the increase in general well-being from regular exercise, it's hardly grounds for the help to be laughing.

In contrast, a talented attorney can spend those 30 minutes billing at $1,200 per hour, and use the income to ensure access to a private room at the Cleveland Clinic for a quadruple bypass, valve replacement and experimental treatment for Type II Diabetes.

One wonders whether Jim Fixx has any regrets?

Kim Zussman adds:

Which begs for a present-value calculation for doctors who run 30 minutes a day from $1200/hr lawyers.

Which begs for a present-value calculation for doctors who run 30 minutes a day from $1200/hr lawyers.

Nigel Davies writes:

The time could be used to listen to talking books and the like. Plus it would be interesting to see if cycling on an exercise bike would produce similar results in which case one's options are much more varied (eg trading and cycling).

Of course the other thing they didn't measure is quality of life. Not much fun having a blonde on one's knee whilst struggling for breath and wondering if one will survive the experience.

Mar

30

Review of Greenberg, from Kim Zussman

March 30, 2010 | Leave a Comment

The underwhelming "Greenberg", played by Ben Stiller, is Hollywood's latest glamorization of neurosis. Woody Allen, the pioneer in this genre, charmed up his leading men (himself) by laundering neurotic obsession through talent. "Shine" put light on a Jewish Australian music prodigy who is rescued from his illness by a high chinned maternalistic matron. Nerds who are crazy but smart, inexplicably winning the girl.Hollywood women veered from the winning Jewish neurotic toward the gentile variant. Jack Nickolson capitalized on his money as a talented writer with OCD in "As Good as it Gets". And the tolerant wife of the Beautiful Mind of John Nash (who in real life got busted for perversion in a Santa Monica beach public toilet).