Mar

16

Physical vs. Mental Errors in Sport & Life, from Bo Keely

March 16, 2011 |

It's tournament time in Racquetown, USA. where ten courts arranged in two rows with a gallery plank above and between them is about to bust open with first serve. The left row hosts the beginner through Open divisions, and the right is strictly pros and racquetball Legends. Soon, we'll take a comparative squint at their physical vs. mental errors, and intentions.

It's tournament time in Racquetown, USA. where ten courts arranged in two rows with a gallery plank above and between them is about to bust open with first serve. The left row hosts the beginner through Open divisions, and the right is strictly pros and racquetball Legends. Soon, we'll take a comparative squint at their physical vs. mental errors, and intentions.

The first two terms are my inventions, but intentions have been with us since the first Neanderthal raised a club for advantage.

Physical errors occur when you miss a shot due to a bad footwork, poor swing, or anything not having to do with a mistake in shot selection. Players make physical errors all the time, and it's no big deal, they say. It's true that a corrective lesson, plus practice, insure a diminishing chance of repeating physical errors.

On the other hand, mental errors are faulty brainwork, usually in shot selection. You should have taken a specific shot from a certain court position, but for some reason did not. These errors may be corrected instantly by an assertion of will, even inside tournament pressure. However, unnoticed or uncorrected mental slights become losing habits.

Let's stage the two types of errors before we look in on the action at Racquetown.

Physical errors:

1) You take a forehand back wall shot and miss a killshot because you were tired. This was the ideal shot but it skipped, hence a physical error. 2) Your step up to volley your opponent's lob serve, but your return zooms off the back wall for a plum setup. The analysis is that you made the proper return attempt, but missed, perhaps because it's a difficult shot. 3) You plant to kill a mid-court shot, a logical thought, and miss it because you forget to step into the ball. You call timeout and sequester in the corner to practice stepping into the ball for a minute, and resume with confidence that you've corrected a physical error. Get the idea?

Mental errors:

1) You gaze in front court at an oncoming ball with your opponent behind you, and hit a pass. This is a mental slight, whether or not the pass wins the point. The correct shot in front of the rival should have been a killshot. 2) A ball lofts softly off the front wall that may be volleyed with one step forward, or floor-bounced three steps backward. You choose the later, committing what Ben Franklin called an erratum, a failure in your systematic shot selection. Always step up to volley whenever possible. 3) It's match point serve as you pause inside the service box to gather courage for a surprise serve to his forehand. At the last instant in the service motion, you psyche out and lift the ball for a safer Z-serve that scores an ace. Nonetheless, this is a mental error, so keep your victory speech short.

At the lower skill lever, every rally is fraught with physical and mental errors, and the general rule is the first player to correct them via lessons and practice advances to a higher division. He'll still make a few correctable physical errors in progressing on to the pros, where the rule is no physical errors. It's all mental.

What can you do right now from an armchair to discipline physical and mental errors? Order the mind to be content after a lost rally using perfect shot selection, since a physical flaw has been unearthed to practice.

Also, swear to reinforce regret after poor shot selection wins a rally, since its repetition loses ensuing volleys. Unrecognized mental errors become physical habits over time that takes long practice cures. Worse, mental errors explained away because of won points pave a path to an irrational life.

Physical vs. mental errors is about delayed gratification. Try a game where you and your opponent agree after each rally to pause five seconds to reflect on each others mistakes. Identify the physical and the mental ones. Watch them diminish until the play advances to intentions, talked about shortly.

Physical, and especially mental errors, steamroll from inside to off the court, and into your future. A single erratum now may domino to knock out of a lifetime deal anywhere. This is why it's important after a match to sit down with a Gatorade and pencil, and analyze your repeating physical and mental errors. List the physical ones in a column on a sheet of paper, with a remedy practice drill next to each. List the mental ones in a second column, and next to it a vow or trick not to do it again. Some methods to clear up the mental error column are mantras, mental rehearsal of the right shots, and practicing correct shot selection with a partner who agrees to end the rally, and thus a point against, the first player to use incorrect shot selection.

It becomes apparent that for any given shot the permutations are: 1) No physical or mental error, 2) Physical + mental error, 3) Physical error only, or 4) Mental error only. Charting these helps open door #1 to victory.

What's more important in the overall game: physical or mental errors? Rookies who conquer physical errors such as a poor grip or slow backswing go on to win. Yet, as the skill level heightens with fewer physical errors, mental play keys in. He who commits fewer mental faults then wins.

Strive for errorless games with stick-and-carrot tricks. The most common beginner folly of protecting a weak backhand by running 'around' it for a forehand, or by hitting the ball with into the back wall, is quickly fixed by racquetball's premier early coach, Jeff Leon. For each mental error, the player must drop to the hardwood and do ten pushups. He concurrently praises positive actions.

Intermediate players may place a small pot in a rear court corner, next to a roll of nickels. The house rules are: 1) When you make a physical error, put a nickel in the pot. 2) For every mental slip put in three nickels. 2) Take a nickel out for every point scored. Now, can you get to 21 points before losing all your change to the pot? Want to bet?

I threw carrots and sticks at myself on the court for years hinged on an updated list on my locker of physical and mental errors, till the career autumn as uncovered balls began bouncing twice beyond my reach. Frankly, toward the end, it was easier to store errors in mind as there were so few. Often a rally, game and match- but never a full tournament- passed with zero physical and mental errors.

One lesson from the chart was there is absolutely no such thing as an 'off day' that millions of sportsmen across America fondly lament. Once you peak in a sport, where no further physical training beyond maintenance is required, and the strategies are understood to eschew mental slips, you may not perform badly. What the people are describing as bad days are unrecognized or uncorrected physical and mental errors.

I carried that hypothesis into a ruinous first game at a Madison Pro stop. Nervy Ken Wong had burst into the pro ranks as the first successful Chinese player who used an inscrutable service motion to lob or drive. He stood like a statue in the service box and looked long up into the lights, tossed the ball nearly to the ceiling, and struck a perfect lob or drive serve with one deceptive swing. I couldn't do anything right against him, and the gallery hooted Chinese hex. I exited the court after the first game loss, just not grasping why shots went crooked. I reached into my gym bag for water only to feel slime- a bottle of Prell shampoo had broken coating the racquet grip with soap. I grabbed a spare racquet with a dry grip and re-entered the court for a showdown win. Some mistakes are committed before one enters the court and need to be corrected to take the streaks out.

My peak performance among about 1000 tournament matches was against Mr. Racquetball Marty Hogan at his peak on the front wall-glass exhibition of the Denver Courthouse. In the first game, I made no physical and no mental errors in a state of high difficulty due to the glass and, behind, a sea of bobbing heads screaming 'Hogan!' mixed with Marty's invisible power serves. The ball disappeared into someone's mouth, and suddenly was upon me. After losing the first game, in the second I made one physical and no mental errors. I lost my best match ever- the one that on any other day would have beaten myself-. 21-20, 21-19. I kept my chin up as my opponent was physically and mentally tortured.

It's a ball-buster to run around the court against an unerring human machine. He is the 'control' in the sport experiment, and you are the variable. His game is unchanging, so how you stack up depends entirely on your play. These champs are called Walls, and are invaluable to lose to, or win against, since they identify your mistakes.

My favorite brainy quote from the Racquetball Legends as their 2003 historian and psychologist, is from

Mike Ray, the Andy of Mayberry with a racquet. He gets things done, and quietly. He beautifully describes playing one game against himself, and another against the opponent, simultaneously. 'When I'm on the court I have a strategy that I know if I execute well and the opponent doesn't do anything special, then I'll win. I just hit my shots, repeating the situations I've been in a thousand times before, so surprises are rare in a year. I ignore the score and let the ref keep it because it has no bearing on my shot selection. Often, my opponent walks off the court and I'm left holding the ball, until the ref yells, 'You just won the tournament!''

Mike Ray, the Andy of Mayberry with a racquet. He gets things done, and quietly. He beautifully describes playing one game against himself, and another against the opponent, simultaneously. 'When I'm on the court I have a strategy that I know if I execute well and the opponent doesn't do anything special, then I'll win. I just hit my shots, repeating the situations I've been in a thousand times before, so surprises are rare in a year. I ignore the score and let the ref keep it because it has no bearing on my shot selection. Often, my opponent walks off the court and I'm left holding the ball, until the ref yells, 'You just won the tournament!''

Now let's look in on the play in progress at Racquetown. Glance up-and-down the courts of beginners on the left, and pros on the right, and tally the number of physical vs. mental errors per rally per player. Among the 'C' players, each makes both errors on nearly every shot, so the games are long, sweaty rallies. (Racquetball survived early growing pains because of this.) At the 'B' level, see about half as many mistakes. At the 'A' level, the physical errors are ironed out but mental errors abound each second. In the Open division, we see only one physical error by each competitor per 4-shot rally, but two mental ones.

Then turn around and peek into the pro courts. A player only loses a rally who makes an error in shot selection that the rival invariably rekills. Most pros, except one in an epoch, make one mental error every two rallies.

Leave Racquetown knowing there's room for betterment through awareness and practice.

The professional level of anything is all about intentions. Locke said, 'Intention is when the mind, with great earnestness, and of choice, fixes its view on any idea.' In sport, you study the opponent's face, hands, gait and grace to quietly determine how he will act the next split-second. What is his design? How soon does the scheme dawn on him, and how long before he physically reaches a point of no return and executes it? Observing these signs is to predict first intent, and make a counter even as, or before, he moves.

The opponent, of course, is looking you up and down the same. Hence, second intent evolves during first; a counter to a counter.

The opponent, of course, is looking you up and down the same. Hence, second intent evolves during first; a counter to a counter.

Intention is stretching the mind toward an object, and with practice you will anticipate a competitor's actions before he does. I learned the most about intentions in 3500 straight non-drinking nights in bars studying drunks, along miles of speechless dog and cat kennels, and trails of survival around the globe.

How far intentions reach is problematic: 1st… 5th… in chess predicting ten moves ahead blindfolded. Keep grounded that second intention is reference to signs, properties, guesses and relations among first intentions. Sequentially, third intent is established during second, and so on. Then decide how far you can or want to go.

Most people use intention sequences all the time, without realizing it. Let's look at a model of sport intentions to apply to business, dating and walking under dim streetlamps. Fencing intentions are described by the tactical wheel that teaches that each tactic will defeat the one before it, and be defeated by the one following. The fence, racquet rally, business negotiation, courtroom unfolding, early romance, political race or street brawl is an endless game of Rock/Paper/Scissors revolving around guessed intents by the players. (Rock breaks scissors, scissors cut paper, paper covers rock, and so forth.)

By assuming the opponent's attack while planning yours, you make a choice what move to use in the bout. That's first intent.

When you study the other's first intent in order to plan yours, you assume he is doing the same, and may alter your next move in what is called second intent. If your foe also notes your second intent, it progresses to third, and so on.

Intention doesn't play a large role in boilerplate sport and business, but it's the wild West throughout history for world beaters like Charley Brumfield, Amarillo Slim, Henry Kissinger, Thomas Jefferson and Perry Mason.

In other words, if one of them presents scissors, you can choose rock, and if you guess he or she will choose scissors again, you may assume he's picked something else for the next round, and so forth, perpetually altering your tactics.

In fencing, the first attack is certainly false, making the opponent perform a parry-riposte, while the real attack is a timed stroke against the opponent's riposte. In boxing, the first lesson from the horsehair mat is left jab, right- cross and Palooka's uppercut though a hole. Gunslingers at nineteen paces rely on multiple intent to shoot accurately first.

The problem with hitting on first intent, which is a euphemism for a 'model stroke', is that it's easily anticipated and countered. I favor second intent only, feeling that to journey farther into third intent against superior intellects that I'm accustomed to squaring off with, is suicidal.

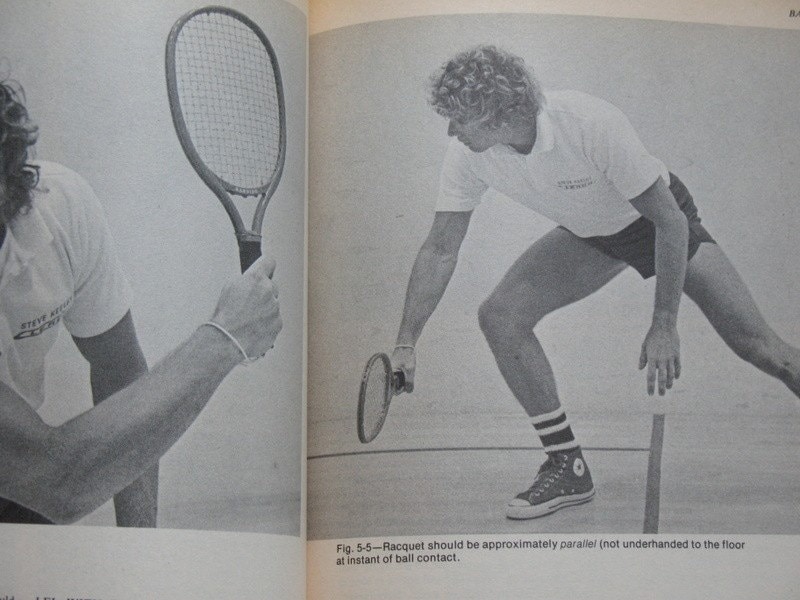

This was the sweat-lesson, evening after evening for two hours, in the upstairs dungeon Michigan State University racquetball courts. No one could see me. I descended every couple of months to bash around in an intramural or fraternity contest, got clipped, and trudged up the steps again. Then one evening I thought of intention, without knowing the word. The next decade of championships in paddleball and racquetball relied on the exclusive stroke strategy of secondary intent. In setting up to swing, I always stepped, looked and angled the downswing (till the instant of ball contact) in precisely the opposite direction the ball was going.

For example, every right-hand killshot to the right-front corner began with a step into the ball cross-court, looking left, and striking the ball waist high. The technique runs tearfully counter to standards, but I wanted to better that, and so build strong first intent into the stroke to fool opponents. My killshot to the right front corner looked like the model stroke of a cross-court drive to deep left. The white lie, forehand and backhand, repeated millions of times in exhibitions and tournaments in a dozen countries without, I believe, anyone reckoning it.

The problem with third intention, and beyond, is that a mental state and stroke built on too many camouflages breaks down with physical exhaustion. Keep it simple, I reminded myself, and win, until all I could do for years is hit second intent shots even after knocked semi-conscious by a ball. In the more poised competitions of baseball and attorney work, you may safely extend into fourth or fifth echelons, reading the opponent's body language and 'mind' to establish his chain of intentions, and evolve your counters.

There's no riddle a computer poker, Jeopardy, or as once I was interviewed by a psychiatrist program, cannot solve. Cold hardware, given the proper juice and circuits, surpasses human. However, bloodless machines move pitifully in tennis shoes, and will never beat a racket player.

So, who are the best of the short line of court sport thinkers in history who committed the least physical and mental errors, hence the strongest 'intentors'? The list embarrasses since, I believe, built into every cerebral champion is a physiological shortcoming that trained his mind. Starting at the bottom, for racquetball,

Ruben Gonzales

Bud Muehleisen

Paul Lawrence

Peggy Steding

Mike Ray

Steve Strandemo

Jason Mannino

Mike Yellen

Charlie Brumfield

And…

The greatest cerebral player is probably Victor Niederhoffer, who for decades plopped around squash, tennis, paddle and racquetball courts more noisily than I. We met to warm up on a St. Louis court at the 1973 national racquetball tournament, each wearing different colored sneakers. He in a black and a white, and I one red and a black. We eyed each other across the service box with first, second… I don't remember how many intentions. I was playing on a sprained ankle with a Converse Chuck on the hurt right, and a low-cut left. I asked myself, 'What does this guy know that I don't?' We've basically been inseparable ever since. There have been countless matches in multiple sports, evenly split, except I always walked away with an intent headache.

Niederhoffer and I entered a NYC squash court just before New Year's 2011 for a hybrid game using a racquetball and he a child's tennis racquet against my wood paddle. He's loosed up over the years, a hip replacement pops, but it's still hard to force his hand by intent. He won a tiebreaker to 11-points, but that night I left the court feeling pretty good for once.

Comments

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- Older Archives

Resources & Links

- The Letters Prize

- Pre-2007 Victor Niederhoffer Posts

- Vic’s NYC Junto

- Reading List

- Programming in 60 Seconds

- The Objectivist Center

- Foundation for Economic Education

- Tigerchess

- Dick Sears' G.T. Index

- Pre-2007 Daily Speculations

- Laurel & Vics' Worldly Investor Articles