Feb

9

Dealership Distrust, from Leo Jia

February 9, 2012 | Leave a Comment

In the past few years in China, I have experienced multiple times insufficient oil fill-ups at oil changes. That happened in different provinces at various so-called 4S dealerships of a premium foreign car brand. The oil was filled up only to the min on the measure. Every time this happened, I reported it to the manufacturer. It seems to be better in recent couple of years.

In the past few years in China, I have experienced multiple times insufficient oil fill-ups at oil changes. That happened in different provinces at various so-called 4S dealerships of a premium foreign car brand. The oil was filled up only to the min on the measure. Every time this happened, I reported it to the manufacturer. It seems to be better in recent couple of years.

It shows that there is a general distrust of dealerships in the country. In recent years, many "good" dealerships offer to display customers' old parts on a shelf so customers can inspect them for themselves. They also would ask before the service confirmation whether the customer would like to take away their old parts. Many also offer large windows or even electronic displays in the waiting lounges in order for customers to see what the technicians are doing with their cars.

Feb

7

The Pressures of Being the Leader of the Pack, from Craig Mee

February 7, 2012 | Leave a Comment

Does the pressure of being in the lead make you take greater risks to maintain it, or do you feel like you have to prove yourself, and show everyone you're a well deserving winner, allowing hubris to rear its ugly face.

Does the pressure of being in the lead make you take greater risks to maintain it, or do you feel like you have to prove yourself, and show everyone you're a well deserving winner, allowing hubris to rear its ugly face.

In Golf, Kyle Stanley bounced back from a bitter defeat to win the Phoenix Open on Sunday, erasing an eight-shot deficit to claim victory a week after his last-round collapse at Torrey Pines.

Alan Millhone replies:

Hi Craig.

I have had the honor of being referee at several world title checker matches. The top Grand Masters when in the lead will be content and play for draws and thus force their opponent to take chances to get a win.

Leo Jia writes:

Being in a leading position is generally tough. First, the leader in a group doesn't automatically get enough motivation to advance. Secondly, he is in an unfair situation where the next win is generally considered a nonevent while a slip to the second position is considered a disaster.

In Chinese idioms, there are some that promote leading. Such as:

First argument occupies the mind; Act first to get the advantage; Voice up the strengths first to forestall the opponent; Be like a crane standing among chickens;

Then, there are many that are against leading:

Sticked-up head gets shot; A man dreads fame as a pig dreads being fat; Protruding rafters rot first; The outstanding tree gets destroyed by wind; The excellent craftsman gets most denies from all craftsmen;

Generally there are more negativity toward leading. Looking back to historic events, a crown prince (a leader of all princes) is perhaps the most dangerous position one can get. From similar reasoning, one key teaching of Confucius is the doctrine of the mean , which basically tells everyone not to stick his head out.

The relative advantage of the leader from the rest (the second and the third for instance) is also very interesting. Consider A, B and C to be the leading, the second, and the third parties respectively. The difference between B and C relative to the difference between A and C is a determining factor in relationships. If B is closer to C (than to A), then generally, B and C will form a union to fight A. Conversely, if B is closer to A, then A and C will very likely form a union to fight B. In either situation, C always has an illusion of being the most advantageous to form a union with A, which as a matter of fact is the most detrimental to itself as well as to B.

A famous ancient novel based on real history called Romance of the Three Kingdoms depicts the above relationships very well. The story happened between 169 AD and 280 AD, when the three kingdoms within the current China's territory: Wei (A), Wu (B), and Shu (C) dealt and fought amazingly amongst themselves, with incessant conspiracies and strategies, all seeking to conquer the entire territory.

Here is the Wiki Page about the novel. An online English version of the entire (long) novel apparently can be read here.

Jan

31

Let’s play a little game of “Baron Rothschild”, from Rocky Humbert

January 31, 2012 | 2 Comments

Let's play a little game — it's called “Baron Rothschild” — who once said “I made my fortune by selling too early” (a comment also made by Bernard Baruch)… Suppose that the dealer lays cards down, one after another. Each is an annual market return. At any time, you can call out “Baron Rothschild” and go to a defensive position, or you can gamble and get the entire market return the dealer shows next. The gain cards read, say, 15%, 20%, 25% and 30%. If you're defensive, you lag the market by 10% when the market return is a gain, but you get, say, 5% if the market return is a loss. There is one -20% loss card. Once it appears, the game ends and everyone counts their dough, compounded. It turns out that if the loss comes anytime before the 5th card, you're almost always ensured to beat or tie the dealer by immediately blurting out “Baron Rothschild” even before the first card is shown. For example,

Let's play a little game — it's called “Baron Rothschild” — who once said “I made my fortune by selling too early” (a comment also made by Bernard Baruch)… Suppose that the dealer lays cards down, one after another. Each is an annual market return. At any time, you can call out “Baron Rothschild” and go to a defensive position, or you can gamble and get the entire market return the dealer shows next. The gain cards read, say, 15%, 20%, 25% and 30%. If you're defensive, you lag the market by 10% when the market return is a gain, but you get, say, 5% if the market return is a loss. There is one -20% loss card. Once it appears, the game ends and everyone counts their dough, compounded. It turns out that if the loss comes anytime before the 5th card, you're almost always ensured to beat or tie the dealer by immediately blurting out “Baron Rothschild” even before the first card is shown. For example,

20%, 20%, 20%, 5% beats 30%, 30%, 30%, -20%

15%, 15%, 15%, 5% beats 25%, 25%, 25%, -20%

20%, 10%, 5%, 5% beats 30%, 20%, 15%, -20%

5%, 5%, 5%, 5% ties 15%, 15%, 15%, -20%

You can easily prove to yourself that even for a six-year market cycle, you still generally win even if you call out “Baron Rothschild” after year two. It just doesn't pay to risk the big loss. The point of this isn't that investors should always take a defensive stance — some market conditions are associated with very strong return/risk profiles that warrant substantial exposure to market fluctuations. The point is that the avoidance of significant losses is generally worth accepting even long periods of defensiveness. Because of the mathematics of compounding, large losses have a disproportionate effect on cumulative returns. Remember that historically, most bear markets have not averaged 20%, but approach 30% or more. A 30% loss takes an 80% gain and turns it into a 26% gain. It's difficult to recover from such losses, which is why the recent bull market has not even put the market ahead of Treasury bills since 2000 or even 1998. So again, the point is that the avoidance of significant losses is typically worthwhile even if, like Baron Rothschild, one is defensive "too soon." With regard to present stock market conditions, it would take a correction of only about 10% in the S&P 500 to put the market behind Treasury bills for the most recent 3-year period. That's not an empty statistic given rich valuations, unusual bullishness, overbought conditions, rising yield trends, and a market long overdue for such a correction. Given the average return/risk profile those conditions have historically produced, it makes sense to call out "Baron Rothschild" even if we allow for the possibility of a further advance, in this particular instance, before the market inevitably corrects.

1) Let's assume that one's goal is to beat some passive index (it doesn't have to be stocks; it could be the Yen or Natgas) over an X month period. And let's further assume that one is willing to engage in "selling early." And lastly, let's assume that "selling early" is sometimes the "right" thing to do due to the essay above. As a statistical matter, what is the likely minimum value for X … that permits the speculator to beat his passive index?

2) Let's assume that one's goal is to beat a passive index (again, it doesn't have to be stocks) over an X month period. And let's further assume that one is willing to exit the market "early," but also "buy early." Obviously, if one exits, re-entering is a necessary thing to do. As a statistical matter, what is the likely minimum value for X … such that the speculator can beat his passive index?

3) As a purely statistical matter, which should be better/worse : Buying early and selling early? Or, buying late and selling late ? And, again, what is the minimum X month performance period where either strategy has a chance to beat the passive benchmark.

William Weaver writes:

1. Disposition Effect

2. Great essay and the observation of defensive over aggressive is very good but I can't agree with purely taking profits unless there is a reason to exit. Assuming sufficient liquidity, in my humble opinion, it might not be bad to tighten stops (volatility historically has fallen as equities rise - though high levels in the late 1990's - so stops based on standard deviation should tighten anyway) allowing one to lock in profits but continue to profit from any trend that develops or continues. This seems to be a prominent trait of the most successful traders I've met; allowing profits to run by controlling for risk instead of picking a top.

3. The saying "There is nothing wrong with taking small profits" is a great way to lose everything if you don't also control for losses. In this essay there is only an early exit for profits.

4. His analysis of the equity premium to Treasuries is very insightful but I will leave that to the list for independent testing.

5. Every trader is different and must play to their own personality. For me, when trading intraday (which I am new to and still not the biggest fan of but am coming along) I will take off part of a position when anything changes, and this helps manage risk (leads to a larger percentage of profitable days). But will wait for long term momentum to reverse before exiting the last half as this is where the majority of my monthly profits come from. This way I can be a wuss and still profit.

6. Read The Disposition Effect if you have not and are interested in any type of trading/speculation. (To add to things to do to become a successful speculator: know, understand and be able to identify behavioral biases both in your own trading, and in the market).

Leo Jia writes:

I don't fully understand Rocky's 3 questions at the end. Guess they are meant for some real speculations, rather than for the Baron Rothschild Game, right?

If so, then I take Will's approach as described in his Point 2, except that I don't exit on instant stops, but on closing prices of certain intervals (30 minutes for instance for position trades) if the means of the intervals trigger my stops. My feelings about instant stops are that 1) they tend to have more execution errors (due to price chasing), and 2) either they get triggered more often or I have to set them wider (meaning more losses). I don't have concrete results about this and would love to hear other opinions.

I can't see how the game closely resembles trading. From what I understand about it, there seem to be many more winning cards than losing ones. So a strategy of simply selling on random cards gives one an easy edge to beat the dealer (though not necessarily achieving the best result). Am I missing something there?

Steve Ellison adds:

Turning to writings from 100 years ago, a friend found this book in his attic in Montana and gave it to me: Fourteen Methods of Operating in the Stock Market.

The first article in this book was A Specialist in Panics, which has been discussed on the List before. This method is to buy when there is a panic.

There was another article by H.M.P. Eckhardt, "Plan for Taking Advantage of the Primary Movements". He advised buying during steep market declines, as the Specialist in Panics did, but also suggested selling if a rapid rise brought profits equal to the interest the investor could have earned over three or four years. Mr. Eckhardt surmised that, with his money already having earned its keep for at least three years, the investor would probably get a chance to put it back to work in less than three years when another panic occurred.

For these sorts of techniques, Rocky's X is the length of a business cycle, which is unknowable in advance, but would normally be at least 48 months.

Alston Mabry writes:

Let's say you start at January, 2004 (arbitrarily chosen start date, but not cherry-picked, i.e., not compared to other possible start dates), and you go to January 2012. You have $100 a month to invest. You can buy the SPY and/or hold cash. You have a total of 97 months and thus, $9700 to invest. If you buy the SPY every month (using adjusted monthly close), you wind up with:

$11,451.37

But being a clever speculator and wanting to buy the dips, you come up with a plan: You will let your monthly cash accrue until SPY has a large drop as measured by the monthly adjclose-adjclose; each time the SPY has such a drop, you will put half your current cash into SPY at the monthly close. To decide how large the drop will be, you compute the standard deviation of the previous 12 monthly % changes, and then your buying trigger is a drop of a certain number of SDs. Your speculator friends like the plan, but disagree on the size of the drop, so each of you chooses a different number of SDs as a trigger: 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, and the real doom-n-gloomer at 4.

The results, showing the size of the drop in SDs required to trigger a buy-in, the final value of the portfolio, and the average cash position during the entire period:

SD / final value / avg cash

0.5 $11,522.13 $543.03

1.0 $11,328.42 $737.77

1.5 $10,885.80 $1,351.02

2.0 $10,884.15 $2,083.36

2.5 $10,655.96 $2,711.34

3.0 $11,005.72 $3,704.12

4.0 $9,700.00 $4,900.00

You, of course, chose 0.5 SDs as your trigger and so come out with the biggest gain. But your friend who chose 3 SDs says that he *could* have used his larger cash position to invest in Treasuries and thus have beaten you. You say, "Coulda, woulda, shoulda."

Mr Gloom-n-Doom cheated and bought the TLT every month and wound up with $14,465.56.

Jan

30

Ten Steps One Should Take to Become a Successful Speculator, from Victor Niederhoffer

January 30, 2012 | Leave a Comment

I am often asked what ten steps one should take to become a successful speculator.

I am often asked what ten steps one should take to become a successful speculator.

I would start by reading the books of the 19th century speculators, 50 Years in Wall Street, The Reminiscences of a Stock Operator by Markman, and others.

Next I would read the papers of Alfred Cowles in the 1920s and try to compute similar statistics on runs and expectations for 5 or 10 markets.

Third I would get or write a program to pick out random dates from an array of prices, and see what regularities you find in it compared to picking out actual event or market based events.

Fourth, I would read Malkiel's book A Random Walk Down Wall Street and update his findings with the last 2 years of data.

Fifth, I would look at the work of Sam Eisenstadt of Value Line and see if you could replicate it in real life with updated results.

Sixth, I would start to keep daily prices, open, high, low, and close for 20 of so markets and individual stocks and go back a few years.

Seventh, I would go to a good business library and look at the old Investor Statistical Laboratory records of prices to see whether it gave you any insights.

Eighth, I would look for times when panic was in the air, and see if there were opportunities to bring out the canes on a systematic basis.

Ninth, I would apprentice myself to a good speculator and ask if I could be a helpful assistant without pay for a period.

Tenth, I would become adept at a field I knew and then try to apply some of the insights from that field into the market.

Eleventh, I would get a good book on Statistics like Snedecor or Anderson and be able to compute the usual measures of mean, variance, and regression in it.

Twelfth, I would read all the good financial papers on SSRN or Financial Analysts Journal to see what anomalies are still open.

Thirteenth, of course would be to read Bacon, Ben Green, and Atlas Shrugged.

I guess there are many other steps that should be taken that I have left out especially for the speculation in individual stocks. What additional steps would you recommend? Which of mine seem too narrow or specialized or wrong?

Rocky Humbert writes:

All the activities mentioned are educational, however, notably missing is a precise definition of a "successful speculator." I think providing a clear, rigorous definition of both of these terms would be illuminating and a necessary first step — and the definition itself will reveal much truth.

All the activities mentioned are educational, however, notably missing is a precise definition of a "successful speculator." I think providing a clear, rigorous definition of both of these terms would be illuminating and a necessary first step — and the definition itself will reveal much truth.

Anatoly Veltman adds:

I think with individual stocks: one would have to really understand the sector, the company's niche and be able to monitor inside activity for possible impropriety. Individual stocks can wipe out: Bear Stearns deflated from $60 to $2 in no time at all. In my opinion: there is no bullet-proof technical approach, applicable to an individual enterprise situation.

A widely-held index, currency cross or commodity is an entirely different arena. And where the instrument can freely move around the clock: there will be a lot of arbitrage opportunities arising out of the fact that a high percentage of participation is inefficient, limited in both the hours that they commit and the capital they commit between time-zone changes. Small inefficiencies can snowball into huge trends and turns; and given the leverage allowed in those markets - live or die financial opportunities are ever present. So technicals overpower fundamentals. So far so good.

Comes the tricky part: to adopt statistics to the fact of unprecedented centralized meddling and thievery around the very political tops. Some of the individual market decrees may be painfully random: after all, pols are just humans with their families, lovers, ills and foibles. No statistical precedent may duly incorporate such. Plus, I suspect most centralized economies of current decade may be guilty of dual-bookeeping. Those things may also blow up in more random fashion than many decades worth of statistics might dictate. Don't tell me that leveraged shorting and flexionic interventions existed even before the Great Depression. Today's globalization, money creation at a stroke of a keyboard key, abominable trends in income/education disparity and demographics, coupled with general new low in societal conscience and ethics - all combine to create a more volatile cocktail than historical market stats bear out. 2001 brought the first foreign act of war to the American soil in centuries. I know that chair and others were critical of any a money manager strategizing around such an event. But was it a fluke, or a clue: that a wrong trend in place for some time will invariably produce an unexpected event? Why can't an unprecedented event hit the world's financial domain? In the aftermath of DSK Sofitel set-up, some may begin imagining the coming bank headquarter bombing, banker shooting or other domestic terrorism. I for one envision a further off-beat scenario: that contrary to expectations, the current debt spiral will be stopped dead. Can you imagine next market moves without the printing press? Will you find statistical precedent of zooming from 2 trillion deficit to 14 trillion and suddenly stopping one day?

Craig Mee comments:

Very generous post, thanks Victor…

Very generous post, thanks Victor…

I would add, in this day and age, learn tough typing and keyboard skills for execution and your way around a keyboard, so you don't wipe off a months profit in the heat of battle. I would also add, learn ways of speed reading and information absorption, though these two may be more "what to do before you start out".

Gary Rogan writes:

Anatoly, I don't think really understanding the sector and and the niche is all that useful unless one knows what's going on as well as the CEO of the company, which means that in general understanding quite a bit about the company isn't useful to anyone without access to enormous amount of information. It's the subtle, little, invisible things that often make all the difference. There are a lot of people who know a lot about pretty much any company, so to out-compete them based on knowledge is usually pretty hopeless. It is nevertheless sometimes possible to out-compete those with even better knowledge by sticking with longer horizons or by being a better processor of information, but it's rare.

That said, it has been shown repeatedly that some combination of buying stocks that are out of favor by some objective measure, possibly combined with some positive value-creation characteristics, such as return on invested capital, do result in market-beating return. Certainly, just about any equity can go to essentially zero, but that's what diversification is for.

Jeff Watson adds:

In the commodities markets it's essential to cultivate commercials who trade the same markets as you(especially in the grains.) One can glean much information from a commercial, information like who's buying. who's selling, who's bidding up the front month, who's spreading what, who's buying one commodity market and selling another, etc. When dealing with a commercial, be sure to not waste his time and have some valuable information to offer as a quid pro. Also, one necessary skill to develop is to determine how much of a particular commodity is for sale at any given time…. That skill takes a lot of experience to adequately gauge the market. Also, in addition to finding a good mentor, listen to your elders, the guys who have been successful speculators for decades, the guys who have seen and experienced it all. Avoid the clerks, brokers, backroom guys, analysts, touts, hoodoos etc. Learn to be cold blooded and be willing to take a hit, even if you think the market might turn around in the future. Learn to avoid hope, as hope will ultimately kill your bankroll. When engaged in speculation, find one on one games like sports, cards, chess, etc that pit you against another person. Play these games aggressively, and learn to find an edge. That edge might translate to the markets. Still, while being aggressive in the games, play a thinking man's game, play smart, and learn to play a strong defensive game……a respect for the defense will carry over to the way you approach the markets and defend your bankroll. Stay in good physical shape, get lots of exercise, eat well, avoid excesses.

In the commodities markets it's essential to cultivate commercials who trade the same markets as you(especially in the grains.) One can glean much information from a commercial, information like who's buying. who's selling, who's bidding up the front month, who's spreading what, who's buying one commodity market and selling another, etc. When dealing with a commercial, be sure to not waste his time and have some valuable information to offer as a quid pro. Also, one necessary skill to develop is to determine how much of a particular commodity is for sale at any given time…. That skill takes a lot of experience to adequately gauge the market. Also, in addition to finding a good mentor, listen to your elders, the guys who have been successful speculators for decades, the guys who have seen and experienced it all. Avoid the clerks, brokers, backroom guys, analysts, touts, hoodoos etc. Learn to be cold blooded and be willing to take a hit, even if you think the market might turn around in the future. Learn to avoid hope, as hope will ultimately kill your bankroll. When engaged in speculation, find one on one games like sports, cards, chess, etc that pit you against another person. Play these games aggressively, and learn to find an edge. That edge might translate to the markets. Still, while being aggressive in the games, play a thinking man's game, play smart, and learn to play a strong defensive game……a respect for the defense will carry over to the way you approach the markets and defend your bankroll. Stay in good physical shape, get lots of exercise, eat well, avoid excesses.

Leo Jia comments:

Given that manipulation is still prevalent in some Asian markets, I would add that, for individual stocks in particular, one needs to understand manipulators' tactics well and learn to survive and thrive under their toes.

Bruno Ombreux writes:

Just to support what Jeff said, you really have to define which market you are talking about. Because they are all different. On one hand you have stuff like S&P futures with robots trading by the nanosecond, in which algorithms and IT would be the main skill nowadays, I guess. On the other hand, you have more sedate markets with only a few big players. This article from zerohedge was really excellent. It describes the credit market, but some commodity markets are exactly the same. There the skill is more akin to high stake poker, figuring out each of your limited number of counterparts position, intentions and psychology.

Rocky Humbert adds:

I note that the Chair ignored my request to precisely define the term "successful speculator," perhaps because avoiding such rigorousness allows him to define success and speculation in a manner as to avoid acknowledging his own biases. I'd further suggest that his list of educational materials, although interesting and undoubtedly useful for all students of markets, seems biased towards an attempt to make people to be "like him."

If gold is up a gazillion percent over the past decade, and you're up 20%, are you a successful speculator?If the stock market is down 20% over a six month period, and you're down 2%, are you a successful speculator?If you have beaten the S&P by 20 basis points/year, ever year, for the past decade, without any meaningful drawdowns, are you a successful speculator?If you trade once every year or two, and every trade that you do makes some money, are you a successful speculator?

If you never trade, can you be a successful speculator?

If you dollar cost average, and are disciplined, are you a successful speculator?

If you compound at 50% per year for 10 years, and then lose everything in an afternoon, are you a successful speculator?

If you lose everything in an afternoon, and then learn from your mistake, and then compound at 50% for the next 10 years, are you a successful speculator?

If you compound at 6% per year for 10 years, and never have a meaningful drawdown, are you a successful speculator?

If the risk free rate is 6%, and you are making 12%, are you a more successful speculator then if the risk-free rate is 0% and you are making 6%?

If you think you are a successful speculator, can you really be a successful speculator?

If you think you are not a successful speculator, can you be a successful speculator?

Who are the most successful speculators of the past 100 years? Who are the least successful speculators of the past 100 years?

An anonymous contributor adds:

In conjunction with the chair's mention of valuable books and histories, I would append Fred Schwed's Where are the Customers' Yachts?.

In conjunction with the chair's mention of valuable books and histories, I would append Fred Schwed's Where are the Customers' Yachts?.

While ostensibly written with a tongue-in-cheek hapless outsider view of 1920s and 1930s Wall Street, it has provided as many lessons and illustrations as anything by Henry Clews. In this case, I am reminded of the chapter in which Schwed wonders if such a thing as superior investment advice actually exists.

Pete Earle writes:

It is my opinion that the first thing that the would-be speculator should do, even before undertaking the courses of actions described by our Chair, is to open a small brokerage account and begin plunking around in small size, getting a feel for the market, the vagaries of execution quality, time delays, and the like. That may serve to either increase the appetite for such knowledge, or nip in the bud what could otherwise be a long and frustrating journey.

Kim Zussman adds:

The obligatory Wikipedia* definition of speculation is investment with higher risk:

Speculating is the assumption of risk in anticipation of gain but recognizing a higher than average possibility of loss. The term speculation implies that a business or investment risk can be analyzed and measured, and its distinction from the term Investment is one of degree of risk. It differs from gambling, which is based on random outcomes.

There is nothing in the act of speculating or investing that suggests holding times have anything to do with the difference in the degree of risk separating speculation from investing

By this definition one must define risk and decide what comprises high and low risk — which may be simple in extreme cases but (as we have seen repeatedly) is not very straightforward in financial markets

*Chair is quoted in the link

Alston Mabry writes in:

I'm successful when I achieve the goals I set for myself. And rather than a target in dollars or basis points or relative to any index or ex-post wish list, those goals may simply be to act with discipline in implementing a plan and then accepting the results, modifying the plan, etc.

Anatoly Veltman adds:

And don't forget Ed Seykota: "Everyone gets out of the market what they want". I find that everyone gets out of life what they want.

Plenty a market participant is not in it to make money. Fantastic news for those who are!

Bruno Ombreux writes:

This will actually bring me back to the question of what is a successful speculator.

In my opinion success in life is defined in having enough to eat, a roof, friendships and a happy family (as an aside, after near-death experiences, people tend to report family first). You can forget stuff like being famous, leaving a legacy or being remembered in history books. If you are interested in these things, you have chosen the wrong business. Nobody remembers traders or businessmen after their death except close family and friends. People who make history are military and political leaders, great artists, writers…

So you are limited to food, roof, friends and family. Therefore my definition of a successful speculator is a speculator that has enough of these, so that he doesn't feel he needs to speculate. I repeat, "a successful speculator does not need to speculate."

Paolo Pezzutti adds:

I simply think that a successful speculator is one who makes money trading. Among soccer players Messi, Ibrahimovic are considered very successful. They consistently score. They experience short periods without scoring. Similarly, traders should have an equity line which consistently prints new highs with low volatility and a short time between new highs. Like soccer players and other athletes it is their mental characteristics the main edge rather than knowledge of statistics. One can learn how to speculate but without talent cannot play the champions league of traders and will print an equity line with high drawdowns struggling losing too much when wrong and winning too little when right. Before dedicating time to find a statistical edge in markets one should assess his own talent and train psychologically. In this regard I like Dr Steenbarger work. In sports as in trading you very soon know yourself: your strengths and weakness. There is no mercy. You are exposed and naked. This is the greatness and cruelty of markets and competition. This is the area where one should really focus in my opinion.

Steve Ellison writes:

To elaborate a bit on Commander Pezzutti's definition, I would consider a successful speculator one who has outperformed a relevant benchmark for annual returns over a period of five years or more. Ideally, the outperformance should be statistically significant, but market returns can be so noisy that it might take much of a career to attain statistical significance.

Jeff Rollert writes:

I propose a successful speculator dies wealthy, with many friends. Wealth is not measured just in liquid terms.

Should a statistical method be preferred, I suggest he is the last speculator, with capital, from all the speculators of his college class.

In both cases, I suggest the Chair and Senator are deemed successful, each in their own way.

Leo Jia adds:

If I may wager my 2 cents here.

I would define a successful speculator as someone who has achieved a record that is substantially above the average record of all speculators in percentage terms during an extended period of time. The success here means more of a caliber that one has acquired which is manifested by the long-term record. Similarly regarded are the martial artists. One is considered successful when he has demonstrated the ability to beat substantially more than half of the people who practice martial arts, regardless of their styles, during an extended period of time. It doesn't mean that he should have encountered no failures during that time - everyone has failures. So, even if that successful one was beaten to death at one fight, he is still regarded as a successful martial artist because his past achievements are well revered.

With this view, I will try to answer Rocky's questions to illustrate.

Julian Rowberry writes:

An important step is to get some money. Preferably someone else's. [LOL ]

Jan

20

Will We Stop Wearing Shoes? from Leo Jia

January 20, 2012 | 4 Comments

Inspired by Vic's grandfather's advice "people will never stop wearing hats", I wonder if perhaps shoes will lose favor with people. This seems to have occurred to me. I used to love shoes and bought many. Now since I work mostly from home, a pair of socks or sleepers are what I wear the most. Then since I mostly live in warm climates, sandals are what I wear the most for outdoors. The next is sport shoes for working out. Formal leather shoes, which I have a bundle of, are rarely worn. What is going to happen 50 years from now?

Inspired by Vic's grandfather's advice "people will never stop wearing hats", I wonder if perhaps shoes will lose favor with people. This seems to have occurred to me. I used to love shoes and bought many. Now since I work mostly from home, a pair of socks or sleepers are what I wear the most. Then since I mostly live in warm climates, sandals are what I wear the most for outdoors. The next is sport shoes for working out. Formal leather shoes, which I have a bundle of, are rarely worn. What is going to happen 50 years from now?

Victor Niederhoffer comments:

This will be very bad for China. There is not one manufacturer of shoes left in America. They're all in China an India now. When I worked in Wilkes Barre 50 years ago as tennis pro, there were at least 30 shoe manufactures in the Scranton Valley alone, all of whom where members of the club. Alas, Poor Yorick.

Leo Jia replies:

Hi Vic,

Yes, that would be very bad for China. But I tend to think that it would also not be easy for the world either.

Simply looking at the iPad shares in the world, we can see how big an exaggeration are China's GDP numbers from its real economic contributions/benefits. In the iPad case, China records the full $275 while its real contribution is only $10. I presume the shoes industry (and all others) would be similar only in varying degrees, with many American and European brands taking the big shares.

Look from the other way, China's economy is not as big as we think it is.

Best,

Leo

Jim Sogi writes:

In Hawaii, everyone wears slippers and goes barefoot often. The feet get tough and the toes spread out in a more natural position which is wider. City feet get cramped in misshapen in the form of the latest fashion almost like Chinese foot binding. Native kids who have gone barefoot their whole lives have wide feet with space between their toes.

In Hawaii, everyone wears slippers and goes barefoot often. The feet get tough and the toes spread out in a more natural position which is wider. City feet get cramped in misshapen in the form of the latest fashion almost like Chinese foot binding. Native kids who have gone barefoot their whole lives have wide feet with space between their toes.

There is a new trend in running shoes towards a less structured shoe with a flexible sole that allows the foot to naturally flex during the running motion. Prior technology in running shoes put a large and rigid heel which forced a heel strike, which unintentionally caused greater impact on the knees. The flexible sole allows the foot arch to naturally flex and absorb the impact resulting in less impact to the knees and back. A popular shoe is the five toe design, similar to ancient Japanese toe socks. African runners run long distance barefoot.

Jan

14

Ideas for Investing for the End of the Word, from Marlowe Cassetti

January 14, 2012 | Leave a Comment

I'm thinking of giving 1,000:1 odds that the world won't end in 2012. If you send me $100 I will give you a certified voucher for $10,000 to be paid to the bearer on January 1, 2013. Stand by for further details.

I'm thinking of giving 1,000:1 odds that the world won't end in 2012. If you send me $100 I will give you a certified voucher for $10,000 to be paid to the bearer on January 1, 2013. Stand by for further details.

Now that is a great investment. Anyone want to sponsor an infomercial?

Leo Jia writes:

The idea that the world will end in 2012 is not easily dismiss-able from human psyche. Whether it will happen or not is not the point. What is important is the course of event, or the path of time, leading to it. The collective human nature will make something big out of it (even though the "it" might be nothing). As an individual, we have all experienced worry. We know that while some worries may have merit, most simply come out of nothing and for nothing. I am sure this event will be something around which many different worries will be generated amount human beings. Those are what will move the things for this year.

I understand the "end of the world" is a concept not easily imaginable to most people. Many believers of the event could simply take it as some disaster that has a big harm to part of the world (the movie seems to be depicting this view). The likelihood for that should be substantially higher than the real "end of the world". In this sense, the number of believers (including the derivative ones) should be influentially large.

Jan

14

A History of the Gold Standard, from Stefan Jovanovich

January 14, 2012 | Leave a Comment

This one is Eddy's fault. She wanted to know about the gold standard.

This one is Eddy's fault. She wanted to know about the gold standard.

The authors of the Constitution had two concerns about money - first, they wanted the Federal government to be able to collect taxes to pay veterans' benefits and the cost of future wars; and, second, they wanted no one - the states, private individuals, the Federal government itself - to be able to deal in funny money. They thought they could solve both problems by giving the Federal government a monopoly on legal tender and then requiring Congress to limit the Money used in payment in the United States to Coin - i.e. precious metal. What is fraudulent about our present system is that the Federal government still has its legal tender monopoly but it no longer follows the rules laid out in the Constitution. Instead of using gold coin, the Federal government uses its own bank-created Credit as Money and requires all of us to accept it as the sole legal tender for all debts public and private.

The authors of the Constitution were so suspicious of what Congress might do that they did not even allow it to have a monopoly on Money. They required Congress to allow Foreign Coin to used as equivalents for the United States' own Coin. The authors of the Constitution knew from bitter experience that Congress was capable of being a fraud about money; country had seen the Continental Congress during the Revolution issue IOUs and then require people to take them in payment of the government's own debts. By allowing Foreign Coin to be Money, the authors of the Constitution were assuring that people could refuse to take any funny money that Congress tried to pass off in the future. This is why the Constitution has its specific provisions requiring Congress to "regulate" the Weight and Measure of both U.S. and Foreign Coin. "Regulate" does not mean "make up whatever rules we like" as it does now; it meant "make regular" - i.e. make equal.

Where the authors and the first Congresses made a mistake was in thinking that they could regulate more than 1 kind of precious metal as Money, that they could set by law the ratios of the prices of gold and silver and copper could be fixed, by law. They made this mistake because everyone in the world believed that Money had to have an official Price; it could not be left to the market to decide what Money was worth. (A few oddballs - the Frenchman Cantillon, the Englishman Gresham - knew better. They both observed that Money has to be unitary; otherwise, the smart people will always be swapping the cheaper metals for the more expensive ones.)

Even with this mistake of multi-metalism, the authors of the Constitution succeeded in achieving their aims for U.S. money. Congress was able to be extravagant - to start wars when they did not have the money to pay for them - without permanently destroying the value of the country's savings because no one could be forced to accept anything other than Coin as Money. If Money became short because people and/or the government had used too much credit, the people who had saved Money would find bargains. If people and/or the government became too cautious and hoarded Money, then the rewards for lending and granting Credit would go up. The interchange between Money and Credit would be the fundamental check and balance against future Congresses overreaching their financial authority. Under the Constitution Congress would be free to borrow on Credit like everyone else but it would only be allowed to coin Money or have Coin accepted as legal tender.

What the authors of the Constitution could not imagine is that future Congresses would allow the Federal government to use its own bank-created Credit as Money. That would have seemed to them against all common sense. Everyone in the country had known, from direct experience, that allowing Credit to become Money produced ruin. Savings became worthless, people abandoned work for speculation, and enterprise was destroyed. If the government's Credit was required to be accepted as legal tender, then everyone could go to the government to get their free Money. "Cash" would have no meaning because people could never be required to pay up in Coin. The authors of the Constitution knew that Credit was wonderful stuff. It was easier to use than specie and was flexible; people's ability to promise to pay was not limited by the coins in their pockets. But there had to a limit to how much people could promise and borrow, and that limit was Money; and Money had to be actual stuff that people could demand when they did not want paper, when they doubted that other people's Credit was good. Almost all of the time people would use Credit for trade; they would buy and sell things using Notes because it was the better way to do business. But, in the background of everyone's mind there still had to be the understanding that people could decline further exchange of credit and demand actual payment instead. With Credit there was always going to be the risk that one was getting a devious, suspect instrument of exchange. If people were free, they would trade; and, in trading, they would be certain to deal in all kinds of promises - some of which will be completely ludicrous. These rules would apply equally to the government and to private business. The Constitutional gold standard would not prevent people or Congress itself from committing fraud and folly; but it would assure that they were punished and not rewarded if Money was the stuff that was impossible to counterfeit and impossible to multiply with the stroke of a pen or the turn of a printing press (or, today, the click of a keyboard).

We now live in a very different world of Money and Credit. Foreign Coin is no longer a check and balance on Congress' monopoly authority over legal tender; every government in the world now uses its own IOUs as Money. That leaves only the Constitutional gold standard as a restraint on the government and people's ability to expand Credit without limit. The country has been here before. During and after the Civil War, the Federal government's IOUs - its Greenbacks - were made legal tender, by law. Many people thought this was fine and wanted Congress to keep printing Greenbacks to pay for rebuilding the country after the war. What Ulysses Grant understood was that if Congress kept spending Money as it had during the war, it would turn the country into a nation of monetary alcoholics. The demand for Credit would never be restrained. Almost single-handedly Grant forced the Congress to commit itself to restoring the gold standard, to promising to redeem all paper money in gold Coin. Many people were horrified by the idea; the New York Times (surprise!) predicted that there would be complete panic. Speculators tried to buy up all the country's gold. But, on the actual day when the Federal government resumed the convertibility of all U.S. Bank Notes into gold coin, the world did not rush to the Treasury to swap its paper for specie. The monetary day of judgment failed to appear and was, in fact, a big yawn. The very act of committing the U.S. to restoration of the Gold Standard had sufficiently re-established the credit of the U.S. government that people were content to continue to deal in the credit notes as if they were as good as gold - which they were.

The same result would happen today if Congress adopted a new Specie Act. I know this is a fantasy; but imagine that Congress enacted and the President signed a Specie Act that legisltated that, after January 1, 2013, U.S. Money would be a Liberty Coin of a fixed Weight and Measure of gold and all government Credit Notes - the paper currency called Federal Reserve Notes printed by the U.S. Treasury - would be convertible into Liberty Coin at the value set by the market . The market would instantly value our current Greenbacks at their worth would be in gold. A dollar whose fluctuating value would be fixed by the market's dealings would not, by itself, save the credit of the United States; but it would instantly end the further abuse of that credit by the Congress and the Federal Reserve. That might, by itself, be enough.

A promise to pay can, as the original J. P. Morgan said, only be valued by the character of the borrower. As long as Money itself is solid, people can accept the risks of Credit as the price of its convenience and opportunity for gain. The very argument used against the gold standard - its inflexibility - is true; when one is well established, the price of gold itself becomes monotonously steady. It is the price of Credit that fluctuates. After President Grant's demand for resumption was enacted into law, the infamous Gold Room closed; and stock and bond markets and bank clearings in the United States exploded with a boom that was so real that it produced enough wealth that the country could, for the first time in its history, afford broad "higher" education.

It will not surprise you and it would not have surprised the authors of the Constitution that the first thing the new generation of professors and well-educated (sic) students did was decide that the archaic system of the gold standard had to be improved. The result was the funding of two World Wars and other systematic tortures that the world is still living under in the name of Progress.

Leo Jia comments:

Thanks Stefan. Here are my thoughts on what you wrote.

From economic point of view, the functions of money are: 1) medium of exchange, 2) unit of account, and 3) store of value.

The biggest problem with fiat money (as we experienced) is its obvious inability to store value. On the other hand, commodity money is hard to transport. Recognizing these, many are inclined to accepting some kind of representative money, such as the gold standard.

It is understandable that people put more trust in things such as gold for a better store of value than in fiat money, simply because they are more real and can't be created from thin-air. This might be very true in simple or primitive economies. But is there any false reasoning here for modern economies? It is true that they can not be as easily created, but this in no way could necessarily lead to a conclusion of their better ability to store value or perform other money functions. My observations are as follows.

1) Any real thing (such as gold) changes value vis-a-vis other real things as economy develops through time. This is determined by the varying needs of human activities. In this sense, a lumber producer for instance may have good reasons not to trust gold to reserve his value of work (as gold could get cheaper while lumber gets dearer during some period of time).

2) The economic developments, following technological advancements or wars for instance, come in steps, which at many times are interruptions to old developments. After each step of development, the values of many thingsare largely re-adjusts. With the automobile invented for instance, the horse wagons lost substantial value. On the other hand, with a large gold mine discovered, gold's value vs. other things dive.

3) In the case of a step-up of the economy (due to an important technology break through, for instance), the requirement for capital jumps up. If the money is based on some real thing (such as gold), the money supply seriously lags in a way to hinder the economy development. Gold's supply has its own course of development. Except for a few large discoveries in history, gold's supply has been largely a gradually growing process, and this contrasts the nature of economic development, which often jumps, particularly in the modern age.

4) In the case of gold being a money base, the real question is why people would always treasure gold. Could the attitude change? From the nature that gold is of little real use, this is very likely somewhere down the road. All it needs is one country's abandoning the gold standard to wreck the whole world's economy. Before that happens, is people's pursuit of gold quite similar to a fool's game, where everyone owning gold is just hoping to sell it to a bigger fool?

In the modern world, when we have various developments in fast gears, we don't really have a money that meets the functions we want. It is very unfortunate. Perhaps the desire to have a store of value in something is generally a fallacy. Sure, the modern finance provides some possibilities for that desire, but modern finance is not for everybody.

Question: is it feasible to form a money based on some financially structured instruments?

Stefan Jovanovich replies:

Leo, Thanks for the reply. I don't think you can support the notion that Money is a primary "medium of exchange" any more; it is, for the limited population of drug dealers and others wanting to hide their wealth from "the law", but the volume of credit transactions so completely dwarfs cash dealings now that I am afraid the standard textbook definition of money has to be retired from our discussions, even if it will always remain the correct answer for an Econ 1 class. The "store of value" notion has always been a canard. The notion of "value" itself is one of those Platonic ideas that it is impossible to abolish, precisely because it is never defined well enough to be tested or disproven. It is part of the equally bizarre idea of Capital - the notion that certain stuff and paper (in our age, digital entries) represent a "store of value". Once you accept the circularity of these terms, you never find the exit door into what people are actually doing. (Yes, yes I know about marginal utility, etc. but all of those wonderful theories can be reduced to something the money changers sitting outside the Temple knew - price is always a matter of quantity and time.)

Having endured the interminable sermons of their era (and decided, like Washington, that God existed outside of church as well as in), the authors of the Constitution were well acquainted with the theological approach to discussions about the economy. But, being practical men of business (even the lawyers among them were traders), they knew enough of the world to know that commerce would always rest on the foundation of credit. When counter-parties began to worry, "the economy" was in trouble, no matter how much gold was in the vault. They also knew that Money - specie - would always be the measure of the fundamental economic fact of life - scarcity. They counted on the fact that Money is always in short supply to be the principal limitation on the size of government itself. As the Founders knew, money is the spoil sport - the stuff that is unalterably real and cannot be talked into existence. Americans used to know this instinctively. There is the classic remark of t he real estate speculator in San Diego in the 1880s who got caught long and telegraphed to his partner back East: "Lost $100,000; still worse, $800 was in cash".

What the Founders and a majority of Americans in the 19th century did not think was that the government could somehow protect people from the vagaries of the market itself. They certainly did not think that gold - i.e. Money - could do that. The claims made for gold by the Paulistas - Don Ron made it again last night in the Republican primary debate in South Carolina - are specious. Gold is not a "store of value" and it has never protected people from the fluctuation of prices. As you noted, gold's exchange value fluctuates dramatically even under a Constitutional gold standard. Gold as Money is no more immune to market variation than Credit; both are subject to the vagaries of trade. What Gold as Money is not subject to are the manipulations of the government as ruled by faction. When George Washington warned against "faction", he was not cautioning people about political parties; he was cautioning them about the ability of people to use the government's monopoly au thority over legal tender to create credit in their particular favor. All gold offers is the assurance to the holder of Money that he/she has only one financial risk - the fluctuations of the market - and that he/she is safe from the cheats of government action in the name of the common good.

P.S. Your history about gold mining needs revision. The great discoveries - California in the 1840s, South Africa and Alaska in the 1890s - did not see "gold's value vs. other things dive"; on the contrary, the gold discoveries led to credit booms that saw general prices rise and specie become inexplicably tight. The Panic of 1907 arose because the London insurance companies were unable to pay their American claims from the San Francisco Fire; gold - within a decade of the greatest discovery in history - became so incredibly short that JP Morgan - for the first time in its history - agreed to join the New York Clearing House so that the banks would stop pulling each other down to ruin by acting like lobsters trying to climb over each other out of a barrel.

P.P.S. The notion of a Monetary base is beyond my capacity to argue with. If you accept the illusion that IOUs are Money, that the entries on the ledgers at the Federal Reserve and the Notes printed by the U.S. Treasury are somehow more "high-powered" than other forms of Credit, then the Ptolemaic system of modern academic economics seems to work fine - until, of course, it doesn't. The modern world has no problems with its system of Credit; its difficulties are with the absurd notion that the Unit of Account can be multiplied at will by central banks in the name of stability.

The questions of money and credit were not intellectual novelties for the founders or their contemporaries. They were - literally - the common coin of civil discourse. Hume's Essays - which were in the library of everyone who attended the Constitutional Convention - raised the issue directly:

"It is very tempting to a minister to employ such an expedient, as enables him to make a great figure during his administration, without overburthening the people with taxes, or exciting any immediate clamours against himself. The practice, therefore, of contracting debt will almost infallibly be abused, in every government. It would scarcely be more imprudent to give a prodigal son a credit in every banker's shop in London, than to impower a statesman to draw bills, in this manner, upon posterity. What then shall we say to the new paradox, that public incumbrances, are, of themselves, advantageous, independent of the necessity of contracting them; and that any state, even though it were not pressed by a foreign enemy, could not possibly have embraced a wiser expedient for promoting commerce and riches, than to create funds, and debts, and taxes, without limitation? Reasonings, such as these, might naturally have passed for trials of wit among rhetoricians, like the panegyrics on folly and a fever, on BUSIRIS and NERO, had we not seen such absurd maxims patronized by great ministers,(Robert Walpole) and by a whole party among us (the Whigs)."

Peter Saint-Andre comments:

And hence there runs, from the first essays of reflective contemplation of a social phenomena down to our own times, an uninterrupted chain of disquisitions upon the nature and specific qualities of money in its relation to all that constitutes traffic. Philosophers, jurists, and historians, as well as economists, and even naturalists and mathematicians, have dealt with this notable problem, and there is no civilized people that has not furnished its quota to the abundant literature thereon. What is the nature of those little disks or documents, which in themselves seem to serve no useful purpose, and which nevertheless, in contradiction to the rest of experience, pass from one hand to another in exchange for the most useful commodities, nay, for which every one is so eagerly bent on surrendering his wares? Is money an organic member in the world of commodities, or is it an economic anomaly? Are we to refer its commercial currency and its value in trade to the same causes conditioning those of other goods, or are they the distinct product of convention and authority?

And hence there runs, from the first essays of reflective contemplation of a social phenomena down to our own times, an uninterrupted chain of disquisitions upon the nature and specific qualities of money in its relation to all that constitutes traffic. Philosophers, jurists, and historians, as well as economists, and even naturalists and mathematicians, have dealt with this notable problem, and there is no civilized people that has not furnished its quota to the abundant literature thereon. What is the nature of those little disks or documents, which in themselves seem to serve no useful purpose, and which nevertheless, in contradiction to the rest of experience, pass from one hand to another in exchange for the most useful commodities, nay, for which every one is so eagerly bent on surrendering his wares? Is money an organic member in the world of commodities, or is it an economic anomaly? Are we to refer its commercial currency and its value in trade to the same causes conditioning those of other goods, or are they the distinct product of convention and authority?

From On the Origin of Money by Carl Menger

Stefan Jovanovich writes:

Menger was the leading figure in the Austrian "Währungs-Enquete-Commission, the Monetary Commission called to deal with the problem of the Austrian currency. (Hayek: "Towards the end of the 'eighties the perennial Austrian currency problem had assumed a form where a drastic final reform seemed to become both possible and necessary. In 1878 and 1879 the fall of the price of silver had first brought the depreciated paper currency back to its silver parity and soon afterwards made it necessary to discontinue the free coinage of silver; since then the Austrian paper money had gradually appreciated in terms of silver and fluctuated in terms of gold. The situation during that period — in many respects one of the most interesting in monetary history — was more and more regarded as unsatisfactory, and as the financial position of Austria seemed for the first time for a long period strong enough to promise a period of stability, the Government was generally expected to take matters in hand. Moreover, the treaty concluded with Hungary in 1887 actually provided that a commission should immediately be appointed to discuss the preparatory measures necessary to make the resumption of specie payments possible. After considerable delay, due to the usual political difficulties between the two parts of the dual monarchy, the commission, or rather commissions, one for Austria and one for Hungary, were appointed and met in March 1892, in Vienna and Budapest respectively.)

Menger was the leading figure in the Austrian "Währungs-Enquete-Commission, the Monetary Commission called to deal with the problem of the Austrian currency. (Hayek: "Towards the end of the 'eighties the perennial Austrian currency problem had assumed a form where a drastic final reform seemed to become both possible and necessary. In 1878 and 1879 the fall of the price of silver had first brought the depreciated paper currency back to its silver parity and soon afterwards made it necessary to discontinue the free coinage of silver; since then the Austrian paper money had gradually appreciated in terms of silver and fluctuated in terms of gold. The situation during that period — in many respects one of the most interesting in monetary history — was more and more regarded as unsatisfactory, and as the financial position of Austria seemed for the first time for a long period strong enough to promise a period of stability, the Government was generally expected to take matters in hand. Moreover, the treaty concluded with Hungary in 1887 actually provided that a commission should immediately be appointed to discuss the preparatory measures necessary to make the resumption of specie payments possible. After considerable delay, due to the usual political difficulties between the two parts of the dual monarchy, the commission, or rather commissions, one for Austria and one for Hungary, were appointed and met in March 1892, in Vienna and Budapest respectively.)

According to Hayek, "Menger agreed with practically all the members of the commission that the adoption of the Gold Standard was the only practical course." What the Commission did not do was adopt the approach taken by the Americans a decades earlier. Instead of simply setting the weight and measure for Austrian Coin at an equivalence to the British pound - the reference point for all international transactions, the Commission debated "the practical problems of the exact parity to be chosen and the moment of time to be selected for the transition". That, by itself, did no great harm; but it established the principle - now universal - that the state, not the market, would be the ultimate arbiter of the content of Money. It is foolish of me to expect them to have done otherwise. Even though (or perhaps because) Menger was the author of utility theory, his political economy had an unshakeable belief in "essences", in the notion that political economy could be reduced to laws of motion, just like physics. The result was the Franco-Germanic idea of the "universal bank" - the Creditanstalt that would literally "manage" the economy and do away with the need for those messy people - the brokers and the dealers in stock - and their volatile exchanges.

For Menger there could be no difference between "the disks (and) documents" because all money was a creation of the state's authority. The American idea that you could bring bullion to the Mint and demand that they reduce it to legal tender - for free - was anathema.

Jan

12

Some Thoughts on Investing, from Leo Jia

January 12, 2012 | 1 Comment

Just did some searches and found 6 apocalypse theories for Dec. 21, 2012.

Just did some searches and found 6 apocalypse theories for Dec. 21, 2012.

Though they can be judged by many as BS theories, they are not trivial ones, and should have many believers.

A search on Amazon for 2012 yields these popular books.

There are also some analysis from the scientific side regarding likely potential disasters that could happen at any time, including the strengthening solar storms, the earth's weakening magnetic field, the super volcanoes both under the sea and on land, etc. All this strengthens people's belief about the incoming apocalypse.Depressed feelings from world economies will also exacerbate for the belief. Further on that, people's herding instinct will tremendously increase the number of believers.

What is more important is how people think others believe in it, and more, how people think others think others believe in it, and so on. My feeling is that these derivative expectations will be very strong. The two sides (believers and non-believers) will become polarized as we move on in the year, with the believers dominating as we come closer to the date.

Is it reasonable to expect the following for this year and beyond from all this?

1) Ordinary investment assets will have high volatility (due to large fights between believers and non-believers), resulting in a depressing trend (possibly a panicking one) for later part of the year (believers win). This should apply to real-estate, arts, antiques, many commodities, and the overall stock markets.

2) Some consumption will see large increases in both price and volume, including entertainment, pleasure, food-drinks, tourism, transportation, luxurism, exoticism, etc.

3) Related equities and commodities will increase in value, but market will still remain downward biased. Most commodities will face backwardation.

4) Interest rates will likely go up, and banks may face liquidity problems.

5) If the world doesn't end as anticipated, world economy will likely have a big recovery in 2013 as a result of all the 2012 activities.

6) Prices will shoot to new highs starting at the end of 2012 for many assets.

Anyhow, with this stone cast, I beg for the real jade.

Jan

12

The Edifice Indicator Update, from Stefan Jovanovich

January 12, 2012 | 1 Comment

China is building 44% of the 50 skyscrapers to be completed worldwide in the next six years, increasing the number of skyscrapers in Chinese cities by over 50%.

Burj Khalifa, at 2,716 feet, should remain top dog for several years, but the Shanghai Tower, at 2,073 feet, and Wuhan's Greenland Center, at 1,988 feet, will take the world No. 2 and 3 spots in 2014 and 2015.

Leo Jia writes:

Not only the number, but the speed of building is also shocking. This story tells about a 30-story hotel being built in 15 days.

Jan

8

A Speculation on Loss-Gain Impacts, from Leo Jia

January 8, 2012 | Leave a Comment

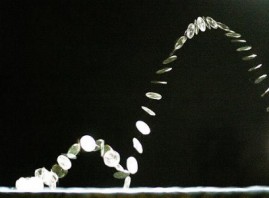

Thinking about Kahneman's loss aversion theory (a loss has about two and a half times the impact of a gain of the same size), I feel that there might be a good reason for it.

Thinking about Kahneman's loss aversion theory (a loss has about two and a half times the impact of a gain of the same size), I feel that there might be a good reason for it.

A loss generates a fear, and a gain generates a joy in a person. The nature of fear in human is that it is recursive: a fear, a fear of the fear, a fear of the fear of the fear, and etc. Joy on the other hand doesn't seem to have this feature. So based on this thinking, fear has a growth effect which can be expressed in terms of the level of recursion n as (1 + 1/n)^n. We see that as n=5, (1 + 1/n)^n = 2.48832. So, if the joy from a gain is 1, the fear from a loss after 5 recursions is 2.48832, which is perhaps just what Kahneman determined through experiments.

Well, why only 5 recursions? That is exactly the question. If the above theory holds, then the theoretically correct number should be the mathematical constant e, which is (1 + 1/n)^n when n approaches to infinity, yielding 2.718281828459. The reason that 2.5 shows up through experiments might be because 1) it is just a rough approximation; 2) recursions in human brains don't really go to infinite levels, a level of 5-6 might be realistic.

Anyone cares to comment?

Kim Zussman writes:

Is there not joy of joy?

If I make a bundle, I am happy. So is my wife, and her happiness makes me happy. And so on with children, friends, business associates, etc.

Another aspect is that you can spend profits any way you like, whereas losses you can't spend in any way.

Leo Jia responds:

My basic understanding of psychology and neuroscience is this (hope someone could help clarify).

The fear is associated with a sub-conscious part of the brain, called amygdala, which takes precedence over the conscious brain in receiving an outside signal. Once this area determines a threat, it could first short-circuit the conscious brain and then sends commands to the body to fight, flight, or freeze. This is a process that could put a normal person under strict arrest. As to how it performs all this, I feel like to think that recursive fear processes (in computer's term) were generated so that it can be powerful enough to override most other bodily needs.

Joy doesn't have this mechanism. It is more of a full brain process involving the conscious brain. So its impact should understandably be limited and single-event, unless of course it is an overjoy.

Jan

7

Thoughts on Irrationality on Bets, from Leo Systrader

January 7, 2012 | 1 Comment

We perhaps have all heard about the following coin toss experiments on people. On each experiment, people have to choose either to play Game A or Game B.

We perhaps have all heard about the following coin toss experiments on people. On each experiment, people have to choose either to play Game A or Game B.

Experiment 1): Game A: the player wins $1000 if head; wins $50 if tail. Game B: the player wins $500 regardless.

Experiment 2): Game A: the player loses $1000 if head; loses $50 if tail. Game B: the player loses $500 regardless.

With Experiment 1), people like to choose Game B.

With Experiment 2), people like to choose Game A.

While I understand this from psychological terms (humans have biases, are not rational etc.), I don't quite understand naturally or fundamentally about what really makes us do this. Hope someone can help explain.

An interesting thing I want to share here is the TED talk (July 2010) below shows that monkeys do in the same way.

Phil McDonnell writes:

These sorts of thought experiments are played on student volunteers at college campuses. Students are notoriously impecunious. Assume a net worth of $300 or so and then calculate the log of the wealth ratio for each outcome. You will find that the most popular outcomes all follow the log utility function.

The mistake the experimenters make is to assume that $1000 is worth twice as much as $500 to a poor student. In fact it is worthless than twice as much. They assume a linear utility function when a non-linear log function is how humans really value things.

Gary Rogan writes:

To understand why any of these biases work the way they do it's best to imagine hominids barely making it in terms of survival rather than even poor college students. There were long stretches where there were more than enough food or other resources, but there were also "funnels" where there were barely enough resources to make it through. We are all descended from the ones who made it through the "funnels". The ones who made the wrong bet left no survivors (or fewer as the case may be).

So if you've got just enough or almost enough to sustain yourself for the next few days but not after that, you realize that you need to do something soon or else you'll be history after those few days. You need to take a risk, but the weather is really bad, it's cold and stormy (or exceptionally hot, or whatever) and you can't venture out. To make matters worse though, a mildly menacing counterpart shows up and "asks" to share your meager resources. Losing half of what you have with great certainty may very well mean likely death, because you will probably be not in a position to "play" again after the weather gets better. If you calculate a 50/50% chance of winning the fight with your "friend" you will probably go for it, even if it means either a complete loss of your resources (and perhaps your life, but those are now equivalent anyway) or a mild injury.

And now a few days are gone, and your are out of resources anyway. The weather is a little better and you are now faced with walking towards a distant meadow where you are certain to find enough berries to sustain yourself for a few more days or pursuing a large but elusive prey (or trying to take something from a leopard resting in a tree with a fresh catch, or trying to fight it out with a different "friend" for his resources, but all of this uncertain), you go for the berries. You take a certain smaller gain vs. an uncertain larger one when getting enough resources means the difference between life and death.

As for how it comes about, we have neural networks in our brain specifically dedicated to evaluating rewards and costs. That's as proven of a fact as anything in neurobiology. Whatever biases worked based to get our distant (and not so distant) ancestors through the "funnels", that's pretty much what we have today.

Phll McDonnell adds:

I think one point that is overlooked in this discussion is that insurance companies do not prefer big bets. Instead they prefer to spread the risk and average out on many small bets. It is also the same reason that earthquake and hurricane insurance is so overpriced. They simply do not want highly correlated bets which increases the risk of serous capital impairment. If they write a lot of earthquake insurance in an area and the big one hits all policies come due at the same time.So they either ration the insurance by charging too much or they simply refuse to sell more than a certain number of policies in a given area.

In a way managing the insurance portfolio is a lot like managing a stock portfolio. You want to avoid bets with large possible negative outcomes and you want to avoid correlated bets. Rather you should take many smaller uncorrelated positions so no one position can wipe you out.

Leo Systrader comments:

Great points here. Many thanks for all the thoughts.

Question to Philip (maybe to everyone) about the non-linearity of human value. It is understandable, but I wonder if there is any scientific conclusion about it.

Let's see if we can use this theory to re-construct the experiment. Let's also assume the net worth of the players is $500. For simplicity, let's just try Experiment 1).

Experiment 1): Game A: the player wins $X if head; wins $Y if tail. Game B: the player wins $500 regardless.

We hope we can come up with an X value that is attractive enough for the players to choose Game A. Also we need to make sure that Game A does not have a significant favor of probability, so we choose Y in such a way that the expected value of Game A is not much more than that of Game B, which is $500. Apparently X will need to be much larger than 1000, so that means Y will have to be a negative number to balance out.

As the theory suggests, to make log(X) = 2 * log(500), X is about 25,000. Let's make the expected value be 600, we get Y to be -23800.

So then Game A becomes: the player wins $25000 if head; loses $23800 if tail.

Would that make people choose Game A? Not to me. Anything wrong in the above analysis?

On the other hand, we know that Kahneman has a theory saying something like "a person's magnitude of pain from losing amount D equals that of his joy from gaining amount 2.5*D".

So let's use this theory to reconstruct Game A.

Let's first decide for Y to be 300. Comparing with the 500 in Game B, the player considers a loss of 200 in Game A. So we need to make X a gain of 2.5 times 200 from 500, so we get X = 2.5*200 + 500 = 1000.

So now we have a new Game A: the player wins $1000 if head; wins $300 if tail.

I guess now it is very likely people would choose Game A over Game B. But we note that the expected value of Game A now is $650

If we make Y to be 50. It is a loss of 450 from Game B. So we make X =

2.5*450 + 500 = 1650.

Game A becomes: the player wins $1650 if head; wins $50 if tail.

Would they play it? Probably, right? In this case, the expected value is 837.5.

Phil McDonnell responds:

Assume a starting net worth of 500.