Oct

15

Charts, from Victor Niederhoffer

October 15, 2013 | 2 Comments

From Anatoly Veltman:

I just saw this Weekly SP chart, and it's honestly… Ugly (link).

I can't imagine how we're supposed to be Bullish on such chart. Mock me all you want, I am no buyer here, sorry. I'll probably miss another tremendous growth opportunity.

Victor Niederhoffer comments:

Needless to say my silence about the chart interpretations should not be taken as acceptance. And aside from the ecology of markets, deception, avoidance of fear, relation to music and barbeque and sport, longevity, board games, etc, the whole genesis of this site from its founder was to avoid such mumbo jumbo.

Gary Phillips writes a poem:

beware of greeks bearing gifts

and single data points

they support a myopic view

and play into the hands of the deceivers

at any given point in time

an equally compelling case

can be forged in either direction

depending on one's bias

the thing about charts

is that they fail to let one see

the markets for what they are,

but instead, for what they appear to be

Kim Zussman writes:

Charts! Charts!

Like musical Tarts

The more you looks

The more it smarts

So look away

From Siren curves

Or you will get

What you deserves

anonymous writes:

I refer everyone to Bruce Kovner's quote regarding the utility of charts below. If you have a better track record than he does, then you are entitled to mock his wisdom. I will gladly wager that no one who is reading this comes anywhere close to his long-term, continuous, audited track record.

There is a great deal of hype attached to technical analysis by some technicians who claim that it predicts the future. Technical analysis tracks the past; it does not predict the future. You have to use your own intelligence to draw conclusions about what the past activity of some traders may say about the future activity of other traders.

For me, technical analysis is like a thermometer. Fundamentalists who say they are not going to pay any attention to the charts are like a doctor who says he's not going to take a patient's temperature. But, of course, that would be sheer folly. If you are a responsible participant in the market, you always want to know where the market is – whether it is hot and excitable, or cold and stagnant. You want to know everything you can about the market to give you an edge. Technical analysis reflects the vote of the entire marketplace and, therefore, does pick up unusual behavior. By definition, anything that creates anew chart pattern is something unusual. It is very important for me to study the details of price action to see if I can observe something about how everybody is voting. Studying the charts is absolutely crucial and alerts me to existing disequilibria and potential changes.

Gary Phillips writes:

Indeed, I look at 22 charts on 4 screens myself. But, what I should have said while in my rush for cynicism, is no one single chart stands out and provides me with a competitive advantage or a forward-looking view of the market; at least not in the time honored edwards and magee kind-of-way. But when charts are related to a broader network of market events, themes, and correlated markets, etc., and provide (to borrow from the chairman) a consilience, then one can assess the departures from value that govern trading opportunities. which is what, I may say, you do so well.

Victor Niederhoffer adds:

Please forgive my not using the term "armchair speculatons" or "furshlugginer" with reference to all those untested hypotheses and impressionist descriptives but not predictive things about chart movements and also ideas about secular bearish markets when we are within 1% of all time high, and a Dimson 1 buck in 1899 would have risen to 60,000 at present.

Scott Brooks writes:

I say this respectfully. Vic and I have jousted on this front several times (and I believe the back forth has always been good natured). But my overarching point on secular bear/bull markets is valid to the average investor.

The extreme highs and lows we've experienced since 2000 is all well and good for the speculator who can take advantage of the market ups and downs.

But to the average 401k investor, 2000 - 2013 has been the lost decade (plus 3+ years).

Yeah, they've continued making deposits and benefited from DCA'ing. But for far too many of working class Joe's, there is very little gain outside of deposits.

The trader can benefit from the market movements. Johnny Lunchbucket has no idea what to do except to move his money around chasing last years returns, and after a few years of that, he is just flat out frustrated. Johnny Lunch Bucket and Working Class Joe do not care that the market is near all time highs. What they intuitively know (maybe even only on a subconscious level) is that even though the market is near all time highs, they've lost something far more important–13+ years of time for that their money should have been, but wasn't, compounding.

I'm not trying to be contentious with the Chair….I'm just trying to present a different POV that many on this list never experience….the plight of the average investor.

Gary Rogan comments:

Scott, the average investor is handicapped by having the urge to sell low. If you sold during the 2008/2009 lows and waited to get in you are certainly left with a very negative impression of the market that feels like a bear market. The only feasible way for an average investor to think about the market is to look at their 45 or so year workspan as the period to evaluate market performance. 13+ years should mean nothing in that frame of reference. Now, if you start investing when you are 55, it means a lot, but you are doing the wrong thing so getting the wrong impression comes with that.

It is true, in my opinion, that the market today is expensive by such measures as total capitalization to GDP ratios. This is somewhat likely to limit returns in the next 15 years although it means very little for the next say 7 years, but within any 45 year period starting from 45 years ago to 45 years into the future market returns are likely to remain close to their historical average (barring a major calamity). The average investor who knows next to nothing should learn this very simple behavior: put a certain percentage of your income into stocks every year, and stop complaining.

Scott Brooks responds:

The best thing that the middle class working man who who is NOT eligible to invest with top tier money managers (due to accredited investor rules) and is stuck with 15 expensive mutual funds in his 401k or his cousins fraternity brother as a broker or some State Farm guy as his insurance agent, is TIME.

Over time he can make handle the ups and downs. But the fact that the S&P peaked at around 1550 in '00, and is now in 2013 getting ready to hit 1700 means he wasted 13+ years with less than a 1% average annual growth rate. Sure, he picked up a point or two in dividends and maybe benefited from DCA'ing….assuming he wasn't one of the many that stopped putting in money into their 401k's for whatever reason (got scared, saw his pay cut or his job outsourced or his spouse got laid off….or whatever)…..but when you subtract out management fees and 401k fees, he almost certainly netted 1% and maybe less.

That my friends is a secular bear market…..and that's the world that 90% of America has lived in for the last 13+ years.

We gotta remember that people on this list are not like the rest of the country, and it's easy to lose sight of that.

I hope it is clear to everyone that I don't pretend to be something that I'm not. I don't pretend to be a counter or even a trader. I'm a simple man who was raised in a lower middle class world and 90% of my family still lives in that world. I'm not trying to raise anyone's ire with these posts. I'm just trying to shed some light on a subject that is very real…..

And maybe somewhere in my words there is a way to create even more profit for those of us that are blessed with:

1. a brain that works better than 95% of the population and

2. have a burning desire to use that brain to it's fullest.

Oct

3

A Chart, from Victor Niederhoffer

October 3, 2013 | 1 Comment

"Business Insider: The Stock Market Looks Like 1967 All Over Again"

"Business Insider: The Stock Market Looks Like 1967 All Over Again"

A chart overlay showing similarities between the S&P in 1993 and this year appears below in this article. I have seen other overlays by the bespoke group showing almost exactitude with this market and I believe 1926 or some such. Harry Roberts, where are you, with your proof that random charts look just like stock market charts. What are the chances that such idempotent overlays would occur by chance if you could pick out the closes match over the last 93 years or so.

Rocky Humbert adds:

And 1954 too. From that link:

U.S. stocks are trading virtually in lockstep with 1954, the best year for American equity and the time when shares finally recovered all their losses from the Great Depression.

The Standard & Poor's 500 Index's returns in 2013 are tracking day-to-day price moves in 1954 almost identically, according to data compiled by Bespoke Investment Group and Bloomberg.

In no other year are the trading patterns more similar to 2013 since data on the index began 86 years ago. The correlation coefficient between this year and 1954, when the benchmark gauge rose 45 percent, is 0.95 out of a maximum of 1.

Kim Zussman writes in:

Using SP500 weekly returns for 2013 (Jan - Sept), checked correlation of these 39 weekly returns with weekly returns of prior 39 week periods back to 1950.

Here are the 10 most correlated:

Date Correl Month

09/30/13 1.000 9

01/05/70 0.506 1

04/11/55 0.506 4

02/19/80 0.482 2

07/26/65 0.479 7

11/12/12 0.476 11

07/21/97 0.450 7

06/21/04 0.448 6

09/21/64 0.436 9

04/08/85 0.431 4

The current 39 week period correlates perfectly with the current 39 week period.

Next closest correlation was the period ending January 1970.

The most correlated Jan-Sept period ended Sept 1964, which along with $7.95 will buy a cup of coffee.

Sep

19

Market Return Perception and Timescale Transformation, from Kim Zussman

September 19, 2013 | Leave a Comment

Is there a better way to map time-series data to reflect the (presumably) non-linear perception and memory of market events?

Log transformation of the price axis seems a reasonable approximation for reaction to price. But what about transformation of timescale as well? How long do significant market events influence current judgement, how are they weighted, and at what rate does this influence fade in comparison with recent events?

Let's assume that traders are not influenced by events more than 1600 trading days ago. SP500 daily return 1960-present was log transformed:

lnRET = ln (today's close / yesterday's close)

These traders care more about recent events than past events. Partly because memory is not conserved, and partly because many processes in the biological world are more logarithmic than linear (eg visual and auditory dynamic range). "Countback days" are simply the count of days from the present to the past, from 1 to 1600. Weighting consisted of scaling each day's lnRET by it's respective ln(countback day)

Current "return perception" of SP500 is the sum of 1600 prior lnRET values, each weighted by ln(countback day):

Current return perception = sum (1-1600) {lnRET/lncountback day}

This process was repeated back in time, starting from March 2013 to Jan 1960 (attached)

current transformed perceived return = sum (lnprice/lncountback days)

The chart of current return perception shows an all-time peak in year 2000. There were large amplitude variations in the 1970's-1980's, then in the early 90's return perception took off. In terms of 1600 day perception, the 2001 bear market never fully recovered, and the 2008-09 decline appears similar to the bear market ca early 1970's.

Sep

13

Rocky’s Challenge, from Rocky Humbert

September 13, 2013 | 1 Comment

Voyager 1, launched back in 1977, has become the first man-made object to pass into the unknown vastness of interstellar space. News Report.

Voyager 1, launched back in 1977, has become the first man-made object to pass into the unknown vastness of interstellar space. News Report.

I have a serious challenge for you. Name a single man-made device that has worked continuously for 40+ years without any human physical intervention. The winner will receive Rocky's usual prize: A unique gift of dubious monetary value.

Chris Cooper has a go at it:

There must be any number of vintage self-winding watches that still work. If it must be wound, does that still match the spirit of your inquiry? Of course, there are many watches and clocks which must be wound by hand that are still operating. You can find some self-winding watches for sale on eBay.

Kim Zussman replies:

I am man-made and have worked continuously for well over 40 years (though currently half time for the government).

Bill Rafter adds:

Without doing any looking, there are lots of low-tech human creations that have survived the test of time. Many dams have performed their functions for decades and even centuries. I'm not speaking of hydroelectric dams, but simple river control devices. The Marib dam in Yemen is still there (after two millennia) and would be working if there was enough rainfall. Many artificial harbors also have exceptional longevity. Some Roman harbor constructions are still operational; the Romans having been expert in concrete manufacture. And don't forget Roman roads.

In more recent times, I am certain there is some electrical cable that is still functioning from half a century ago, if only to ground lightning rods.

Sep

2

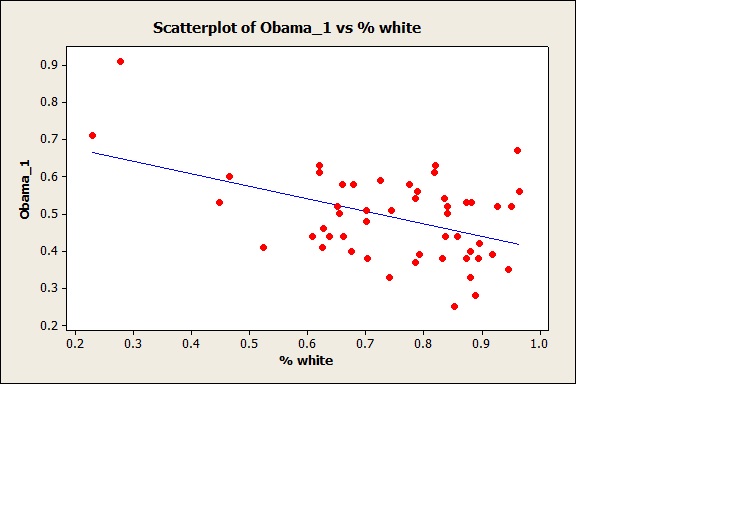

President Obama, from Kim Zussman

September 2, 2013 | Leave a Comment

Evidently the "red line" was the one crossed from below by the market in the last minutes Friday.

Aug

23

Hot Tightwads, from Kim Zussman

August 23, 2013 | Leave a Comment

"A Penny Saved is a Partner Earned: The Romantic Appeal of Savers"

"A Penny Saved is a Partner Earned: The Romantic Appeal of Savers"

Abstract:

The desire to attract a romantic partner often stimulates conspicuous consumption, but we find that people who chronically save are more romantically attractive than people who chronically spend. Saving up to make a particular purchase also enhances one's romantic appeal, as long as the planned purchase is not materialistic. Savers are viewed as possessing greater general self-control than spenders, and this perception mediates the relationship between spending habits and attractiveness. Because general self-control also encourages healthy behaviors that promote physical attractiveness, savers are viewed as more physically attractive as well. However, general self-control is not always coveted in potential mates: dispositional and situational factors that increase the need for stimulation reduce the preference for savers. Nevertheless, capitalizing on the general preference for savers over spenders, people are more likely to deceptively describe themselves as savers when completing a dating profile than when completing a private questionnaire. Our work sheds light on how a fundamental consumption behavior (spending and saving decisions) influences the formation of romantic relationships.

Aug

22

The Fact that the Dax Was Up, from Victor Niederhoffer

August 22, 2013 | Leave a Comment

The fact that the Dax was up 3 ratio points against the US markets shows that the largesse of the flexions on our numbers is not withheld from those who make recipes for the bernaise and bechamel sauces in Brussels .

The fact that the Dax was up 3 ratio points against the US markets shows that the largesse of the flexions on our numbers is not withheld from those who make recipes for the bernaise and bechamel sauces in Brussels .

Alan Millhone writes:

Dear Chair,

Am afraid the bernaisacky sauce might upset my stomach.

Note Dow was below 15. That is upsetting enough to many without adding any sauces.

Sincerely,

Alan

Kim Zussman writes:

It was dyspepsia from absence of Bernanke sauce.

Peter St. Andre writes:

I really need to write a little poem that starts with "Ben Bernanke makes me cranky"…

Gary Rogan contributes:

There once was a man named Bernanke

Engaged in some bad hanky panky

But he went AWOL

and skipped Jackson Hole

And now the markets are cranky.

Craig Mee adds:

Bernanke the captain of Fed

Resembles Titanic's, Smith Ed

Evades all bergs, engines full out

Bond infinity, no damnable doubt

"Untapered, untwisted, now screwed", he said.

Aug

19

Taking Stock Tips, from Kim Zussman

August 19, 2013 | Leave a Comment

Many years ago one followed the Wall St. Journal stock-picking / dart throwing contest. The Journal claimed that the expert stock pickers were well ahead of the darts over many iterations. Holdings in those days were all mutual funds or indices. So for a first foray into individual stock ownership, I bought shares of "TCBY treats" - a frozen yogurt franchise - which was touted by the analyst in WSJ dart contest.

Many years ago one followed the Wall St. Journal stock-picking / dart throwing contest. The Journal claimed that the expert stock pickers were well ahead of the darts over many iterations. Holdings in those days were all mutual funds or indices. So for a first foray into individual stock ownership, I bought shares of "TCBY treats" - a frozen yogurt franchise - which was touted by the analyst in WSJ dart contest.

His analysis was, "The balance sheet looks good". I checked his background and he seemed well educated and reputable (remember this was pre-enlightenment vis. shibboleths of Ivy degrees and name shops).

I never checked the balance sheet because it was unlikely my novice reading would provide more insight than the market, and in any case the analyst was trained, experienced, and (in essence) endorsed by WSJ.

Some time later the analyst could point to brief intervals when TCBY was higher. However as you might guess the stock went into a long/slow slide into oblivion.

Following recommendations without understanding their basis and the motives of the recommender is risky business.

Rocky Humbert writes:

Dr. Zussman is absolutely correct. One should never ever listen to any recommendations or thoughts that I espouse as my motives are suspect; my analytics are flawed; and my thought processes are clouded by insomnia and senile dementia. (I view these albatrosses as my secret edge in the markets.)

Furthermore, I myself follow Dr. Zussman's advice religiously and assiduously avoid reading newspapers or books, avoid conversations with intelligent people and spent 23 hours per days in a saline-filled sensory deprivation tank (from which I emerge to occasionally pen SpecList posts.)

Gary Rogan writes:

I have been told by many people, on multiple occasions, and for a variety of reason to avoid stock tips, mainly because you can never know exactly why the person likes them and also because they are unlikely to fit into your "trading system" (and I would guess investment system). I find this advice hard to evaluate. I suppose if one knows some stats of the person's previous picks this makes it easier. If you can deduce that the person isn't simply talking their book, that's probably better as well. But fundamentally, a stock can't know that someone has recommended it to you. If you have a system, you should at least know whether the person intends for the pick to be a short-term trade or a long-term investment and judge accordingly. Rocky doesn't give a lot of stock tips, so what should one think of one when it suddenly appears? Hard to know. On the other hand, I think I have a pretty good idea who Rocky really is and he is an upstanding member of the community with a good track record, and can't possibly be thinking of moving AAPL significantly by talking about it here, so is it really wrong to follow his recommendations?

Aug

9

IWM. SPY and Normality, from Kim Zussman

August 9, 2013 | 3 Comments

A question for Kim or Victor: Since IWM has more stocks than SPY, does it follow that daily returns on IWM are closer to the Normal Distribution than SPY? - A Reader

Victor Niederhoffer replies:

It does, as a consequence of the Central Limit Theorem .

Kim Zussman replies:

Let's look at it empirically. Here is the "Anderson - Darling" test for normality of daily SPY returns, 2000-present (SP500).

Next is the same test for IWM (Russell 2000 ETF), 2000-present.

Rocky Humbert writes:

Vic, I'm not sure that the central limit theorem is the right paradigm. An unknown is whether the covariance within the two groups is sufficiently different to offset the CLT. I have never tested this. And testing is tricky because you need to use compounded total returns with dividends reinvested. The index and stock prices produce misleading results because dividends are greater for big caps.

Intuitively, I believe that most of the perceived differences can be explained by 2 things:

1) the dividends…which is really just a duration effect and 2) the reality that companies leave the R2k only when they are incredibly successful or when they die. Stocks only leave the SP500 when they die. They never leave the SP500 and go to the R2k when they are successful. So over time, the perceived differences are a micro sampling of a survivor bias between the 2 indices. Not sure how to test this theory…

What we do know is the implied volatility of r2k is almost always higher than the implied volatility of the SPX. I think this could be an analogue to the fact that out of the money puts are more expensive than out of the money calls. Put another way, if you are long SPX and short r2k in equal dollar amounts, you will usually make money during violent and persistent market downdrafts. I think this is proof that the distributions are different.

Victor Niederhoffer writes:

Those are good points you make about areas that I should have considered in estimating the departures and distributions of comparative performances. It is also amazing to me that the statistical tests, especially the Kolmogorov Smirnov, show such departures. I am a great believer that the risk premium on untried and small stocks is much bigger and that they should perform better and that buying two handfuls of them will have a limiting distribution that converges to a return a percentage or two above the 8 % you get from the average NYSE stock. I must go back and check my premises. It reminds me of how I told the people in my family to buy the riskiest vanguard over the counter fund, and they tell me that they are always getting notes in the mail that the funds I recommended are being sued by their holders as the worst performing funds in history due to all sorts of wrongs of a practical and theoretical nature. I mean this response in a humble and appreciative way although it is sometimes hard to communicate that by email in the face of all the errors that are elicited.

Ralph Vince writes:

Like everything else in this realm, it depends on the unit of time used in analysis. If you use annual data, things play much more nicely to Normal. The shorter the time unit used, the less so.

Jul

8

There Is Only One Silicon Valley, from Kim Zussman

July 8, 2013 | 3 Comments

Interesting article by Vivek Wadhwa in Technology Review "Silicon Valley can't be copied".

(Regrettably omitting the role of resourceful governance).

By 1960, Silicon Valley had already captured the attention of the world as a teeming technology center. […] French president Charles de Gaulle paid a visit and marveled at its sprawling research parks set amid farms and orchards south of San Francisco.

Soon enough, other regions were trying to copy the magic. The first serious attempt to re-create Silicon Valley was conceived by a consortium of high-tech companies in New Jersey in the mid-1960s. [The plan] could not get off the ground, largely because industry would not collaborate.

In 1990, Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter proposed a new method of creating regional innovation centers. […] Sadly, the magic never happened—anywhere. Hundreds of regions all over the world collectively spent tens of billions of dollars trying to build their versions of Silicon Valley.

The reasons [for Silicon Valley's unique success] were, at their root, cultural.

Californian Stefan Jovanovich adds:

There is an element that is not mentioned. California, for better or worse, has always been the place people went to strike it rich. People came to Silicon Valley for the same reason they went up into the Sierras or stayed in San Francisco and sold shovels in the 1850s - they intended to make their fortune, not just get a "good job" (pun intended). What literally disgusts those of us who loved the place is that the same greed exists today but the enterprise is almost entirely directed to fleecing the government in the name of (pick one) "curing cancer, saving the environment, some other socially responsible activity that just happens to attract a good deal of non-profit and government cash". As one of our friends, who left for Idaho a decade ago, said, "Sleaze is always a part of the hustle that comes with "making it new"; but now the whole state is the music business without any new music - everything is just sampling what has already been done and filing a claim to protect what was not even invented in the first place."

Carder Dimitrioff speculates:

Actually, it could be argued that Silicon Valley is a replication of Boston. Up until the Nixon Administration, the greater Boston area was the nation's technology highway. Fed by Lincoln Labs, MIT, Harvard, Northeastern University, Boston University, Boston College, University of Massachusetts, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Clark, Rensselaer and other great technology centers, companies like MITRE, DEC, Polaroid, WANG, and dozens others popped up all over Boston's Route 128.

Then, Massachusetts became the "one and only" state not to vote for Nixon in 1972. Nixon was from California. Silicon Valley is in California. Maybe there is a connection?

Peter Saint-Andre writes:

I forwarded this article to Jim Bennett (co-author of "America 3.0") and he noted:

"One of the under-appreciated factors was Stanford's rule that allowed professors to work part-time for companies and take stock options in pay. Most universities forbid that as being vulgar, as gentlemen are not supposed to engage in trade."

Carder Dimitroff replies:

In my experience, most technology professors in the Boston area were part-time academics. Most wanted to start their companies based on their areas of interest. Most Boston area universities allowed such.

EG&G is an early example. The letters represent the names of three MIT professors. My dad was one of their first ten employees. He worked under Doc Edgerton - not in MIT or Lincoln Labs, but in EG&G, Inc. This was decades ago.

One of my beefs with MIT is their lack of dedicated faculty. Even professors in their Sloan School spend most of their time in consulting firms. A lot of their faculty seem like they are adjunct professors.

Jun

16

Was First Hunch Correct? The Case of the Problematic Tooth, from Ed Stewart

June 16, 2013 | 3 Comments

I have recently had a lot of pain related to a problematic tooth. It is a tooth that has been giving me trouble on and off for years and I have no idea why. Dentists have suggested it suffered some type of trauma when I was younger, but if that was It I don't remember the event.

I have recently had a lot of pain related to a problematic tooth. It is a tooth that has been giving me trouble on and off for years and I have no idea why. Dentists have suggested it suffered some type of trauma when I was younger, but if that was It I don't remember the event.

Went to the emergency room last January (weekend, regular doctor closed) because I was in massive pain over the holiday weekend.

It turns out that it had become infected and was putting pressure on the nerve in the Jaw. Since that time I have had a root canal on the tooth, but that did not solve the problem. I have had two other procedures, the last one this morning because the prior one did not heal properly and got infected again. Really aggravating experience, no need to go in to details. Today I am holed up recovering, jaw aching on a beautiful day.

The thing is, back in January, I had a gut reaction that the best thing to do would be to just forget all the treatments and have the problematic tooth yanked out. Based on the trouble it had caused me to that point, it just seemed to be the solution that made sense — likely to be final and just "end" the problem.

Yet, I was told that was too extreme and "the tooth could be saved" etc. No professional I spoke with thought it was a good idea, in fact they seemed astonished that I suggested it. And today, after treatments and quite a bit of discomfort, things not going right, etc, I am inclined to think my initial hunch was correct. Forget treatment. Just get rid of the problem.

I wonder how often this happens.

A clear cut solution to a problem exists, but a bunch of complex alternatives are presented and the resolve to do what is likely required to the end the problem with certainty is dampened. Not to push the analogy to far, but does this not also happen in trades, businesses, and relationships that are going wrong. Rather than end a problem trade, it is easy to tinker with it, look for hedges, "scalp" around the position, etc. but instead of a resolution only more pain is created. Or a relationship that has stopped working — "keep fixing it" but only more delays for the inevitable split which is more painful than a clean break.

It is hard to tell what is hindsight quarterbacking, and what is a life lesson. In this case I am still not sure which it is. I wonder if there are any general rules or ideas that can be applied to these situations to give better outcomes.

anonymous writes:

Absolutely, the best case is to always treat (your tooth or a losing trade), like it was bad meat and spit it out. Deal with it immediately, no messing around, just take the hit and get over it. Bad trades, like bad relationships, have a way of metastasizing into something worse, and the old cliche comes to mind, "Your first loss is the least."

Personally I remember once having a relationship with a nice gal that went south (but as a guy I was totally oblivious to the whole thing and didn't see the obvious signs). I was out with the lady in question in public at a restaurant and she gave me "the blow-off speech." I was so confused that I didn't even see it coming (One could make a case that infatuation is insanity). In retrospect, I should have gotten up, picked up the check, paid her carfare, bid her adieu, and walked out, never to see or communicate with her again…..like one exits a bad trade. Instead I lingered for months in an emotional limbo, like a sick puppy, suffering great humiliation and many bad feelings. In retrospect, like a bad trade, that relationship wasn't worth it and there was no bargaining, hedging, covering it with options that was going to save it. It had to be pitched immediately, and I broke my cardinal rule by not pitching it (emotions again).

Bad trades, like bad relationships can teach one many lessons in life and trading if one listens to what the situation (market) is telling you. If only, when dealing with that person, I had used my trading persona instead of my emotional side, I would have not lingered in emotional limbo for months.

This supports a great case for dispassion, and a big part of the Masonic obligation is to "learn to subdue your passions." But like the ying and yang, good things happened out of that debacle and I ended up seeing a very cultured, erudite, successful, powerful, and beautiful woman that I married a few months ago. I'm happy for the first time in five years, and that's what's important. Bad teeth, bad trades, bad relationships…..get rid of them, they are just nuisances that get in the way of life.

A commenter adds:

But that thinking of could have, would have, should have is very deadly in the markets. Although hindsight is always 20/20, my eyesight of 20/100 does not allow such indulgences and my defensive game does not allow for such risk. I'm trying to make money, not keep my finger in the dike like the little Dutch boy. The Dutch boy was wasting his time.

Gary Rogan writes:

Bad women and bad teeth rarely get better by themselves, although some teeth that seem to need a root canal sometimes do. Equities do it a lot more frequently, so to this day I don't know how to reliably tell when a bad equity trade needs to be spit out. "Your first loss is the least" obviously applies to some situations, but for instance I still own a stock that lost me 20% two days after I bought it, 50% three months after I bought it, but now two years later it's up 70%, having been up 120%. Rocky talked a lot about his thoughtful decision to exit HPQ back when it was relentlessly moving south, but it's back. What used to be RIMM is still in the dump, but someone who bought it in September doubled their money. If you could always make a wise decision by just getting out of a (currently) losing trade, everyone would be a lot richer than they are.

Rocky Humbert responds:

Mr. Rogan,

Indeed HPQ has been inexorably working its way back and may keep climbing. Who knows? What we do know is what the S&P index has done subsequent to my exiting HPQ. And we also know what other alternative investments (gold, real estate, etc) have done over the same period of time. Taking the hit and putting the (remaining) capital into the alternatives would have been better than suffering. Hence in these matters, one must consider not only the ongoing pain, but also the opportunity cost. To the extent that one is monogamous, the analogy holds for personal relationships.

Is there an opportunity cost for teeth? Not sure.

Gary Rogan replies:

Sure, there is always the opportunity cost. The question is, how well do we know it in advance? My point was that if say you bet all your money leveraged 10 to 1 on wheat, and your position is down 10% you may want to exit, but if you own 100 stocks and one is down 10% or 50% or even 90% what to do at that point outside of any tax considerations and without any additional information isn't exactly clear. Given my preference for 52 week lows in the absence of any other information it may make sense to buy more or do nothing. If the sudden move lower really attracted your attention, and upon further study you conclude that this is only the beginning, of course you may want to sell. But then a sudden move up or a long period of flatlining or something you happen to read or hear may attract your attention as well.

A commenter writes:

The key phrase that piqued my interest was when you said, "you bet all your money leveraged 10 to 1 on wheat." Why would you "bet" all your money? Wouldn't you want to just "bet" a small part of it, and keep the rest of your powder dry? Anyways, betting signifies gambling, and gambling is wrong.

Gibbons Burke writes:

Anonymous, I am like you—I don't see any value in pissing my money away in a known negative expectation game, so I sympathize with your view. I have never found enjoyment in gambling, personally. But I can't extrapolate from my subjective view and experience onto the world because everyone's utility and entertainment functions are different.

Gambling in the United States has several positive social functions… State lotteries support education of children… Gambling on Native American reservations is a voluntary form of reparations to that people… and, it gets money out of mattresses and back into economic circulation, transferring capital from those who are not prudent in their stewardship of that capital (otherwise they wouldn't be gambling, would they) and putting it into hands where it will be more efficiently employed.

Part of the freedoms cherished in this Constitutional Democratic Republic is the freedom to act the fool, on occasion, as long as you don't infringe upon the rights of others, or forsake the duties to yourself or those in your charge.

Kim Zussman adds:

You would not have regretted your decision to accept professional opinion / treatment had everything gone well.

The mistake is assuming you could have made a better decision - to extract the tooth - simply because in hindsight the treatments have not worked.

For any decision there is a range of outcomes. Perhaps your treatment had 80% chance of success (defined as rapid pain reduction, elimination of infection, and saving the tooth). But so far you are in the 20%, and for you the failure feels like 100%. "If only I'd extracted"

Do you expect portfolio managers or sound strategies to never lose, or abandon them only when they do? (Buy high / sell low)

Dentist and physician success rates are mostly unknowable but patients use cues to evaluate them. Cues such as trusted referral, reputation, diplomas, demeanor, looks, office decor, exhibited technology, etc.

Your treating dentists are simultaneously incentivized to obtain good results (reputation, future referrals) as well as make money (perform treatment). Those with consistently poor results have trouble competing with those with good results, and you are less likely to wind up there.

Jun

3

Trader Burnout, from Kim Zussman

June 3, 2013 | Leave a Comment

Inspired by the concept of burnout from the medical world, it might it be useful for traders to review every once in a while as a tool for when to take a break.

Or conversely take out the cane.

May

14

The Difference Between a Speculator and a Gambler, from Larry Williams

May 14, 2013 | Leave a Comment

I first saw the 'dead eyes' look of a poker player/loser when I was 13 or so. Still gives me restless nights and I know I cannot become that way.

I first saw the 'dead eyes' look of a poker player/loser when I was 13 or so. Still gives me restless nights and I know I cannot become that way.

My dad took me into the "stockman's bar" in Billings, Montana to impress upon me what degenerate, greedy people turn into.

Probably another sleepless tonight tormented by that devil.

Gary Rogan asks:

What is the real difference between gambling and speculation (if you take drinking out of the equation)? Is it having a theory about the odds being better than even and avoiding ruin along the way?

Tim Melvin writes:

I will leave the math side of that answer to those better qualified than I, but one real variable is the lifestyle and people with whom one associates. A speculator can choose his associates. If you have ever been a guest of the Chair you know he surrounds himself with intelligent cultured people from whom he can learn and whom he can teach. There is good music, old books, chess and fresh fruit. The same holds true for many specs I have been fortunate to know.

Contrast that to the casinos and racetracks where your companions out of necessity are drunks, desperates, pimps, thieves, shylocks, charlatans and tourists from the suburbs. Even if you found a way to beat the big, the world of a professional gambler just is not a pleasant place.

Gibbons Burke writes:

Here is something I posted here before on this distinction…

Here is something I posted here before on this distinction…

Being called a gambler shouldn't bother a speculator one iota. He is not a gambler; being so called merely establishes the ignorance of the caller. A gambler is one who willingly places his capital at risk in a game where the odds are ineluctably, mathematically or mechanically, set against the player by his counter-party, known as the 'house'. The house sets the odds to its own advantage, and, if, by some wrinkle of skill or fate the gambler wins consistently, the house will summarily eject him from the game as a cheat.

The payoff for gamblers is not necessarily the win, because they inevitably lose, but the play - the rush of the occasional win, the diversion, the community of like minded others. For some, it is a desire to dispose of money in a socially acceptable way without incurring the obligations and responsibilities incurred by giving the money away to others. For some, having some "skin in the game" increases their enjoyment of the event. Sadly, for many, the variable reward on a variable schedule is a form of operant conditioning which reinforces a compulsive addiction to the game.

That said, there are many 'gamblers' who are really speculators, because they participate in games where they develop real edges based on skill, or inside knowledge, and they are not booted for winning. I would include in this number blackjack counters who get away with it, or poker games, where the pot is returned to the players in full, minus a fee to the house for its hospitality*.

Speculators risk their capital in bets with other speculators in a marketplace. The odds are not foreordained by formula or design—for the most part the speculator is in full control of his own destiny, and takes full responsibility for the inevitable losses and misfortunes which he may incur. Speculators pay a 'vig' to the market; real work always involves friction. Someone must pay the light bill. However the market, unlike the casino, does not, often, kick him out of the game for winning, though others may attempt to adapt to or adopt his winning strategies, and the game may change over time requiring the speculator to suss out new rules and regimes.

That said, there are many who are engaged in the pursuit of speculative profits who, by their own lack of skill are really gambling; they are knowingly trading without an identifiable edge. Like gamblers, their utility function is not necessarily to based on growth of their capital. They willingly lose their capital for many reasons, among them: they enjoy the diversion of trading, or the society of other traders, or perhaps they have a psychological need to get rid of lucre obtained by disreputable means.

Reduced to the bare elements: Gamblers are willing losers who occasionally win; speculators are willing winners who occasionally lose.

There is no shame in being called a gambler, either, unless one has succumbed to the play as a compulsion which becomes a destructive vice. Gambling serves a worthwhile function in society: it provides an efficient means to separate valuable capital from those who have no desire to steward it into the hands of those who do, and it often provides the player excellent entertainment and fun in exchange. It's a fair and voluntary trade.

Kim Zussman writes:

One gambles that Ralph and/or Rocky will comment.

Leo Jia adds:

From the perspective of entering trades, I wonder if one should think in this way:

speculators are willing losers who often win; gamblers are willing winners who often lose.

David Hillman adds:

It is rare to find a successful drug lord who is also a junkie.

Craig Mee writes:

One possible definition might be "a gambler chases fast fixed returns based on luck, while a speculator has time on his side to let the market decide how much his edge is worth."

Bill Rafter comments:

Perhaps the true Speculator — one who is on the front lines day after day — knows that to win big for his backers, he HAS to gamble. His only advantage is that he can choose when to play.

Anton Johnson writes:

Anton Johnson writes:

A speculator strives to be professional, honorable, intellectual, serious, analytical, calm, selective and focused.

Whereas the gambler is corrupt, distracted, moody, impulsive, excitable, desperate and superstitious.

Jeff Watson writes:

I know quite a few gamblers who took their losses like men, gambled in a controlled (but net losing manner), paid their gambling debts before anything else, were first rate sports, family guys, and all around good characters. They just had a monkey on their back. One cannot paint with a broad brush because I have run into some sleazy speculators who make the degenerates that frequent the Jai-Alai Frontons, Dog Tracks, OTB's, etc look like choir boys.

anonymous writes:

Guys — this is serious, not platitudinous, and I can say it from having suffered the tragic outcomes of compulsive gambling of another — the difference between gambling and speculating is not the game, the company kept, the location, the desperation or the amounts. The only difference is that a gambler, when asked of his criterion, when asked why he is doing this, will respond with "To make money."

That's how a compulsive gambler responds.

Proper money management, at its foundation, requires the question of criteria be answered appropriately, and in doing so, a plan, a road map to achieving that criteria can be approached.

Anton Johnson writes:

It's not the market that defines whether a participant is a Gambler or a Speculator, it's his behavior.

Gibbons Burke writes:

That's the essence of my distinction:

"gamblers are willing losers who occasionally win"

That is, gamblers risk their capital on propositions where the odds are either:

- unknown to them

- cannot be known

- which actual experience has shown to have negative expectation

- or which they know with mathematical precision to be negative

They are rewarded for doing so on a random schedule and a random reward size, which is a pattern of stimulus-response which behavioral scientists have established as one which induces the subject to engage in the behavior the longest without a reward, and creates superstitious as well as compulsive behavior patterns. Because they have traded reason for emotion, they tend not to follow reasonable and disciplined approach to sizing their bets, and often over bet, leading to ruin.

"speculators are willing winners who occasionally lose." That is, speculators risk their capital on propositions where the odds are:

- known to have positive expectation, from (in increasing order of significance) theory, empirical testing, or actual trading experience

They occasionally get unlucky, and have losing streaks, but these players incorporate that risk into the determination of the expectation. Because their approach is reason-based rather than driven by emotion, they usually have disciplined programs for sizing their bets to get the maximum geometric growth of their capital given the characteristics of the return stream, their tolerance for drawdown.

If a player has positive expected value on a bet, then it is not a gamble at all. The house does not gamble. It builds positive expectation into its games. It is a willing winner, although it occasionally loses.

There are positive aspects of gambling, which I have pointed out earlier in the thread and won't belabor. To say that "all gambling is bad" is to take the narrowest view. Gamblers who are willing losers (by my definition all are) provide the opportunities for willing winners (i.e., speculators) to relieve gamblers of the burden of capital they clearly have no desire to hold onto, or are willing to trade in a fair exchange for the excitement of the play, to enable their alcoholic habit, to pass the time, to relieve their boredom, to indulge delusions of grandeur at the hoped-for big win, after which they will quit playing, or combinations of all of the above.

Duncan Coker writes:

I found Trading & Exchanges by Larry Harris a good book on this topic and he defines all the participants in the exchanges and both gambler and speculators have a role to play. Here is something taken from page 6 that make sense to me: "Gamblers trade to entertain". Speculators to "trade to profit from information they have about future prices."

He divides speculators into those that are well informed versus those that are not. One profits at the expense of the other. Investors "use the markets to move money from the present into the future". Borrowers do the opposite.

May

8

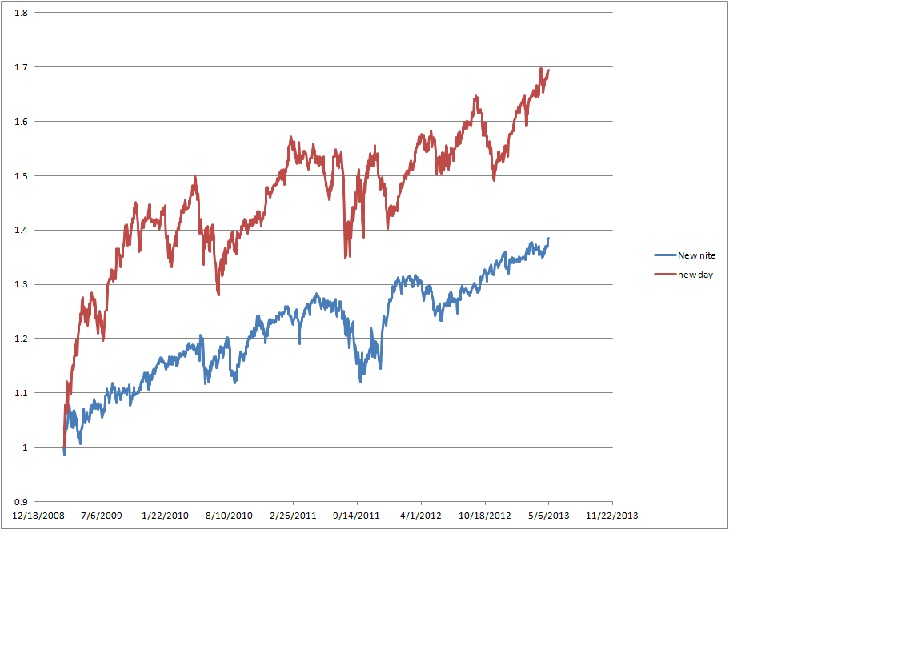

This chart plots compounded return for SPY day and night (open-close, close-open) for the prior bull market of 3/03-10/07. Most of the period's gain occurred overnight, though day returns were strong in the initial rally. The overnight returns were consistently good over the period.

This is a similar chart of compounded SPY day and night returns for the recent bull market 3/09-present. Unlike the prior one, the current bull market was up both day and night with advantage going to daytime returns.

One possible explanation would be the visible hand of Ben and Co: heavily pulling levers during market hours to maximize return (of voters).

Apr

30

Buy in May for Another 7%, from Kim Zussman

April 30, 2013 | 1 Comment

In 2013, stock market return for January - April is about 12% (SPY: Dec 31 - end of april). Going back to 1994, regressed subsequent May- October returns against return of prior Jan-Aprils shows a positive correlation:

Regression Analysis: May-Oct versus Jan-Apr

The regression equation is

May-Oct = - 0.0107 + 0.753 Jan-Apr

Predictor Coef SE Coef T P

Constant -0.01071 0.03092 -0.35 0.733

Jan-Apr 0.7530 0.4125 1.83 0.086

S = 0.115422 R-Sq = 16.4% R-Sq(adj) = 11.5%

Though not quite significant, in the absence of a miraculous recovery in economic activity (and unlikely FED tightening), the regression equation suggests another +7% through October.

Apr

23

There is always something new to someone with many gaps in knowledge like mine. And the minimum spanning tree which I saw in an astronomy article "bootstrap, data permuting and extreme value distributions" by Suketo Bhavsar (which I couldn't understand but sent to Dr. Z as he could and Mr. Grain who could also understand it and it seems like a very good thing for technical analysis. But I will have to study it when not losing in market (all too rare).

Kim Zussman adds:

The article is unfortunately significantly beyond my boundaries. Observationally I would worry also about what we can see vs what is obscured by interstellar dust, but presumably they adjust by using infared (which penetrates dust better).

But I see your point vis traded price path:

"The Minimal Spanning Tree or MST (Zahn 1971) is a remarkably successful filament tracing algorithm that identifies filaments in galaxy maps (BBS; Ung 1987; BL I). The technique, derived from graph theory, constructs N - 1 straight lines (edges) to connect the N points of a distribution so as to minimize the sum total length of the edges. This network of edges uniquely connects all (spans) N data paints, in a minimal way, without forming any closed circuits (a tree). In order to distil the dominant features of the MST from the noise, the operation of "pruning" is performed. A tree is pruned to level p when all branches with k galaxies, where k < p, have been removed. Pruning effectively removes noise and keeps prominent features."

Victor Niederhoffer writes:

But it's descriptive right? I don't see anything about how to use it as predictive?

Kim Zussman replies:

They seem to be trying to lift signal (filaments) from background noise. Do you think some market moves are signal and others noise?

Victor Niederhoffer responds:

Yes. Like when bonds and stocks are both up on the day. The green on our chart or a break of a round number. Like an orgasm. But I can't understand the astronomy of the Indian paper so can't unravel it.

Apr

12

Shave, from Victor Niederhoffer

April 12, 2013 | 2 Comments

Today was a day that I lathered the face at 7:00, and checked on the prices and the shaving cream is still there. Gold down a nice 35 bucks and bonds up a point and stocks down 8. The Dax down 150 and crude down 2 bucks. A take away from the trading. When the pain is too great to withstand adding to the position, and you utter an "oh , no!", that's when you should be standing solid as a stone wall and adding to the fortress, I think.

Today was a day that I lathered the face at 7:00, and checked on the prices and the shaving cream is still there. Gold down a nice 35 bucks and bonds up a point and stocks down 8. The Dax down 150 and crude down 2 bucks. A take away from the trading. When the pain is too great to withstand adding to the position, and you utter an "oh , no!", that's when you should be standing solid as a stone wall and adding to the fortress, I think.

Vince Fulco writes:

I've been looking at some historical chart of the softs and other extreme situations recently and per the Chair's comments it is remarkable how quick and painful the washout can be before the trend changes direction violently and puts on multiples of the initial move.

How many times if we just walked away from the desk for a couple of hours to read, jog, or do anything, would we return back to clover? If only one had the fortitude to stand firm at all times.

Kim Zussman writes:

A possible key is a human inability to shift attention time-scales, i.e, if one is used to thinking (stressing) ticks (minutes, hours, points), it's hard to switch to weeks or months, then back again — in order to be profitable under different states of the market.

It may also help explain early buying and selling.

Apr

8

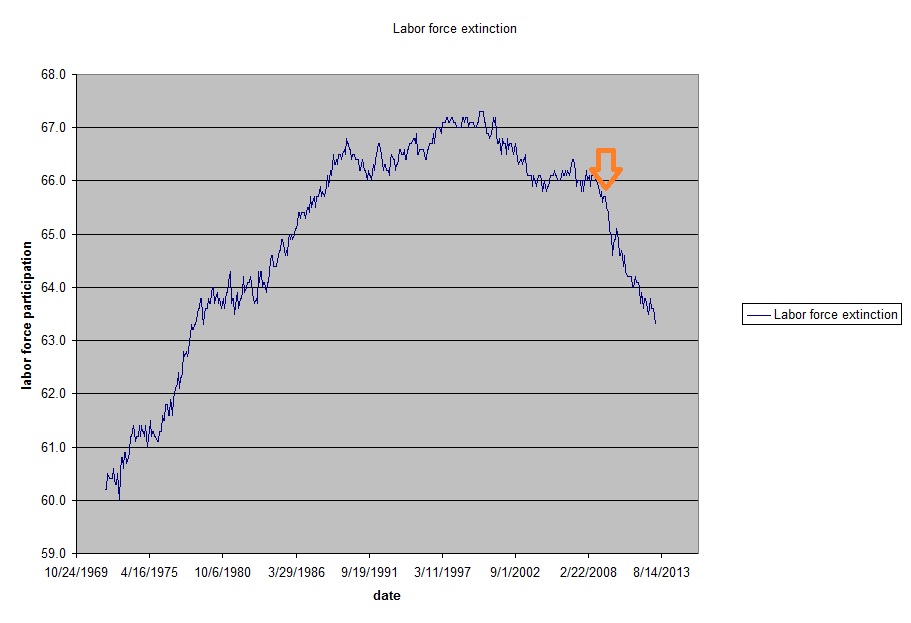

Current Epidemic Extinction, from Kim Zussman

April 8, 2013 | Leave a Comment

Chart is labor force participation rate 1972-present. RED arrow indicates infection point.

Apr

3

Gold, from Victor Niederhoffer

April 3, 2013 | Leave a Comment

Many bearish things about gold lately. That it doesn't go up with no inflation, that we're in recession. That the dollar is going up. That there is great overhand of stocks. I am reminded of a question that I always ask when we hear rumblings that we are going into recession and someone suggests that it is bearish for stocks. I always ask, "what does that have to do with the likely outcome of the stock market? Will the drift be lower or higher?" Oh, I haven't tested that is the unspoken answer. Same for gold. I have not been averse to considering speculative buying of it on all the dips and one is not averse to upholding the spirit of Gavekal idea that it is good to consider things of that nature when caught in Africa by natives, or in large deposits by flexions. One notes a 20 day minimum and is not averse to considering expectations thereafter even before Dr. Zussman runs it on small tab.

Many bearish things about gold lately. That it doesn't go up with no inflation, that we're in recession. That the dollar is going up. That there is great overhand of stocks. I am reminded of a question that I always ask when we hear rumblings that we are going into recession and someone suggests that it is bearish for stocks. I always ask, "what does that have to do with the likely outcome of the stock market? Will the drift be lower or higher?" Oh, I haven't tested that is the unspoken answer. Same for gold. I have not been averse to considering speculative buying of it on all the dips and one is not averse to upholding the spirit of Gavekal idea that it is good to consider things of that nature when caught in Africa by natives, or in large deposits by flexions. One notes a 20 day minimum and is not averse to considering expectations thereafter even before Dr. Zussman runs it on small tab.

Kim Zussman writes:

Using ETF "GLD" daily closes (12/04-present), new instances of 20 day lows were defined as the first 20 day minimum in 20 days. For these new 20 day lows, the return for the next 5 day interval was positive but N.S.:

One-Sample T: next 5D

Test of mu = 0 vs not = 0

Variable N Mean StDev SE Mean 95% CI T P

next 5D 32 0.0012 0.0317 0.0056 (-0.0102, 0.0126) 0.22 0.828

However 7 of the last 10 instances of new 20D lows have been followed by 5 day periods which were down:

Date next 5D

02/11/13 -0.027

12/04/12 0.007

10/15/12 -0.005

06/28/12 0.018

05/08/12 -0.040

02/29/12 -0.004

11/21/11 0.021

09/22/11 -0.067

06/24/11 -0.009

01/07/11 -0.007

07/01/10 0.011

03/24/10 0.025

01/27/10 0.020

12/11/09 -0.003

06/22/09 0.017

03/10/09 0.022

01/12/09 0.047

10/16/08 -0.109

07/30/08 -0.032

03/20/08 0.022

08/16/07 0.010

05/10/07 -0.014

03/02/07 0.008

12/15/06 0.011

08/17/06 0.012

06/01/06 -0.026

02/13/06 0.026

12/20/05 0.050

10/20/05 0.026

08/30/05 0.031

07/06/05 0.002

03/22/05 -0.001

Anatoly Veltman writes:

Fantastic work, as always. Now, I will ask a few skeptical questions:

1. So you test a historical period which saw the price move from $400 to $1600. Wouldn't you expect bullish historical results of a purchase made just about any random day?

2. So we're having a market in 2013, bouncing around on any piece of planted news from Cyprus, from EU, from Putin, from Japan, from Fed, from WH, from investment banks, from fund characters (the ilk of the upside-down), etc. How will one adjust one's timing of statistically catching the falling knife - given that the timing of such leaks (releases) has significantly changed from the test years?

3. Also, the market mechanism has changed in those 8 years, on two fronts:

-the increased weight of ETFs vs. bullion/futures

-the increased prolifiration of HFT exploratory orders

My gist: it's good to have a study, but there are plenty of caveats that call for increased amount of discretion.

In fact, here is my idea: I've observed this to work at an increasing rate since the transfer of investment capital from public into the coffers of the banks and funds has been initiated by the Central authority.

So Gold drops too quickly from $1600 to $1563, which rightfully piqued the Chair's interest in the wee hours. So this is what investment banks, playing with unending public capital, do (for a 24-hour play): they buy momentary cheap Gold and sell Oil against it (got to get the quantity mix right). Oil could not be considered cheap following last week's straight rise. Works plenty of times. And when it doesn't (really, once in a blue moon), a short term spread position becomes a longer term hedge, then the books may get cooked, then a rogue trader is disclosed, etc. who knows…But a good statistical trade to be sure. I like it.

Jason Ruspini adds:

If it seems like HFT is degrading certain strategies over time, there might be testable differences between different futures exchanges that support different order types. For example CME supports stop-limits without any additional software, but Eurex and TSE do not. ICE natively supports ice-berging, most don't. HKFE and SFE only support limit orders natively. Does the performance of benchmark momentum or reversion systems on equity contracts differ between these exchanges (without applying slippage assumptions)? They aren't apples-to-apples of course but if HFT has polluted the microstructure for certain strategies, it seems like something should show-up here, even if many participants have ways to create the other order types.

Ralph Vince writes:

Interesting points Jason. Timely too, I believe.

When market meltdowns occur, the technologie du jour is the scapegoat. In 1929, it was margin accounts. In 1987, program trading. Tomorrow, HFT.

Not that HFT caused the meltdown, but the fact that they stepped aside and enormous air pockets formed in the faveolate theatre of perceived liquidity.

Mar

10

As Usual, from Victor Niederhoffer

March 10, 2013 | Leave a Comment

As usual the reports of employment with all the adjustments to the economic numbers, coming from the government employees at the department chaired by the leader who likes her kids to sing the iron anthem, are designed to increase the importance of the department of the interior and redistribution and vote buying as Nock and Tollison and the public choice people said. First, the revised number from last month (which are 100,000 or so lower than previously reported) + the current number are very poor. And the total is about in line with the past dismal figures. (when will all these revisions be taken into account so that there is not such a big opportunity for the public to do the wrong thing).

The decrease in the unemployment rate comes from all the people who are not looking for jobs because they are on disability or given up hope. Third, the numbers are designed to show that when the rate goes up, they can attribute it to the fact that the survey was taken before sequestration (the economics chair has said this and important pro spending leaders of all sexes have it in her or his talking points already), so that when they report worse numbers in the future they can say it was because of the dreaded effect of reducing gov expenditures over 10 years by 800 billion rather than the fact that the numbers themselves are random.

Kim Zussman writes:

"What is then the connection between these numbers and the market?"

1. If unemployment and GDP numbers continue to improve, Oval Occupier takes credit and proving that higher taxes are pro-growth

2. If it worsens, it can only be due to House Republicans protecting the rich

3. If unemployment and GDP numbers continue to improve in a world without investment alternatives, stocks go up

4. If it worsens, time for more QE - which is now well known to be extremely bullish for stocks

Paving Wall St for Hillary (sorry Ross).

Richard Owen adds:

Always get long a fraud short you think is going to print above consensus. Men with gold filings and lucky silver dollars like their trading sardines.

Also, the disenfranchised pipe welder is the new fifties housewife. Instead of the little woman adding her own egg to the betty crocker brownie mix, the oxy acetelene operator adds his own self pity to a bottle of Jack Daniels. Growth in the fifties was still pretty good.

When Kruschev met Nixon and fulminated that Russia would outpace the US inside of seven years, it is easy to look back and laugh. At the time, much harder to be sure Russia wouldn't win out.

Mar

6

New New High, from Kim Zussman

March 6, 2013 | Leave a Comment

Yesterday (3/5/2013) the DJIA passed its all-time high (not adjusted for inflation); the SP500 has only a couple % to do the same.

Going back to 1950, daily SP500 closing prices were identified which were both an all-time high (starting at 1950), AND the first such occurrence in 100 trading days. There were 19 such instances. For these 19 new all time highs, checked the return for the next 1 day, 5d, 10d, and 20d - here comparing the means to zero:

One-Sample T: 1d, 5d, 10d, 20d

Test of mu = 0 vs not = 0

Variable N Mean StDev SE Mean 95% CI T P

1d 19 0.0010 0.0059 0.0013 (-0.0018, 0.0038) 0.77 0.451

5d 19 0.0047 0.0117 0.0026 (-0.0008, 0.0104) 1.78 0.092

10d 19 0.0040 0.0185 0.0042 (-0.0048, 0.0129) 0.95 0.354

20d 19 0.0061 0.0257 0.0059 (-0.0062, 0.0185) 1.05 0.309

>>not much; the most promising being the 5 days after new all time highs. Below are the dates:

Date

5/30/2007

2/14/1995

8/19/1993

7/29/1992

2/13/1991

5/29/1990

7/26/1989

1/21/1985

11/3/1982

7/17/1980

3/6/1972

4/29/1968

5/4/1967

9/3/1963

11/1/1961

1/27/1961

9/24/1958

3/11/1954

6/25/1952

Feb

27

SPYs in the Early 90s, from Kim Zussman

February 27, 2013 | Leave a Comment

SPY daily data was used to calculate a measure of intra-day volatility normalized to current price:

(H-L) / ((H+L)/2)

SPY data was also used to calculate daily intra-day return: (C/O)-1

These ratios were used to calculate the ratio: return / (intra-day volatility) (return per unit realized volatility, intraday)

The plot of return/volatility over time (1993-present) is here.

The plot looks sufficiently random but for a number of "roundish" points in the 93-94 period. Notice that for most of the series (excepting 93-94), there were no instances of "1" or "-1" (either an up day with intraday return = intraday volatility, or a down day with intraday return = -(intraday volatility) ). But there were several instances of 1, -1 in the earliest period. Also in the same 93-94 period there were a number of "0"s for the ratio - corresponding to zero return.

Hypotheses include problems with the data (Yahoo), and problems with the ETF itself.

Feb

5

A Lobagola of a Lobagola, from Kim Zussman

February 5, 2013 | Leave a Comment

Feb

5

Expertise, Comparative Advantage, and Mortality, from Kim Zussman

February 5, 2013 | Leave a Comment

An expert has great comparative advantage in their area of expertise.

An expert has great comparative advantage in their area of expertise.

They say it takes 10,000 hours of study and mindful practice to become an expert — not to mention the natural talent, and the practice time it takes to maintain expertise.

Since a work lifespan is ~50 years — along with time needed for play, sleep, food, and social interaction — it would be unusual to become expert at many things. Which suggests that the economic fuel of comparative advantage is not likely to go away.

How is expertise possible in ever-changing markets?

Jeff Rollert writes:

I recommend the book Mindfulness, which contains the research work of Harvard psychologist Ellen Langer on observing and problem solving.

I practice some of her ideas when I walk to work…

Jan

30

There is a Zero Sum Part to Trading, from Victor Niederhoffer

January 30, 2013 | 1 Comment

There is a zero sum part to trading where what one flexion makes, another high frequency or day trader or poor gambler ruined or lack of margined or viged player uses. The win win aspect is that if you hold for a reas period as almost everyone in market is forced to do, you get the drift of 10000 fold a century, except if you lived in the Iron and played a game with kings moving backwards.

Anatoly Veltman writes:

Ok, I'll say it. Drift prevails over a century. And I had no problem with drift as recently as 4 years ago, when the only true drifter I know, a prince of certain oil, was adding to his C holdings by bidding pennies.

I'm having a problem with over-relying on drift now; because now, four years later, you can only bid pennies for C if you add $42 in front of it. All the while the real economic indicators, as Chair pointed out just today, have not and will not improve much any time soon. Now tell me: why assume that there will be much of a drift effect in the near five, or maybe the near ten years? Do you expect policy improvements, or pray for a budget spiral miracle, or Europe culture unity miracle, or what other miracle?

Jeff Watson writes:

Back in 1932, the DJIA made a new all time low that wiped out 36 years of gain. Likewise, the market didn't totally recover from 1969's highs until 1982, and the market has done a 15 bagger since then. I'll stick with the drift, which is a steady wind.

Rocky Humbert writes:

There seem to be two sorts of smart-sounding stock market pundits: (1) those who get bearish because prices have risen. (2) those who get bearish because prices have fallen. I am neither smart nor a pundit but my views of the 3-5 year upside from here (small) and current positions (long inexpensive s&p calls) are known to all.

In the face of the current seemingly relentless rise (which has used up a year's drift in 3 weeks)… I confess that I am looking at my new, over 50% combined tax rate, and positing that higher marginal rates disincentive not only my risk-taking, but also my selling (as the taxes discourage my speculative urge to sell now and buy stuff back at hopefully lower prices.)

With this in mind, an academic study might consider whether changes in capital gains tax rates result in more serial correlation (i.e. trending — as I look around three times) SHORTLY AFTER the higher taxes are imposed. And the effect diminishes over time as people become accustomed to the new regime. Obviously I would guess the answer is yes.

Kim Zussman writes:

Increasing tax regime could be bullish:

1. additional vig against frequent trading (as if there weren't enough already) > 1a. "drift" of holding period toward longer timeframe

2. disincentive to sell = incentive to hold and/or buy (including insiders)

3. restructuring away from dividends toward stock buy-backs

Rocky Humbert writes:

Dr Z may be onto something. Does this mean if Obama raises capital gains taxes to 99%, the stock market will triple over night?

Anatoly Veltman writes:

1. I have no problem with counting to include the last few years

2. I have a problem with counting to include anything pre-2007, let alone pre-2001, and even more so pre-1987.

The reason I have a problem with it: historical price analysis, no matter which way analysis is performed, relies on the notion that participants have not largely changed, and that "their" psychology has not changed. This is not the case - if one goes too far back - because financial market mechanism and participant make-up has changed ever increasingly over the past decade.

One of the victims of methamorphosis was "trend-following". I believe that most previosly successful trend-following rules have died in application to regulated electronically executed markets, because most clients are now automatically prevented from over-leveraging. Thus, "surprise follows trend" rule, for example, lost potency. Nowadays, you get preponderance of surprise "against trend". That's a very significant switcharoo, which has put most of famed trendfollowers of yester-year out of biz.

Also, Palindrome was not much off, predicting the other day hedge fund outflows due to old as age "2&20 fee structure". This structure just can't survive the years of ZER environment. Huge chunk of very cerebral participation has been replaced by bank punk punters, gambling public's money for bonuses.

Gary Rogan writes:

The drift seems to be a long-range phenomenon that has existed in different stock markets for a very long time. It is therefore difficult to make predictions of its demise based on any specific factors. One thing is clear: calamities like revolutions end the existence of the market and obviously the drift. Benito Mussolini was very good for the Italian stock market for a long time, and even way into the war it kept up with inflation, but eventually it succumbed to the realities of war (in real, not nominal terms). Granted, Mussolini initially had much better economic policies than Obama, but who would really expect that faschism could coexist with a great stock market? The question still remains: will there be a total wipeout? Short of that the drift is likely to continue.

Il Duce wasn't chosen completely at random, and the question was (just a little bit) tongue-in-cheek.

I could easily make the contention, and a great case, that fascism co-exists with a great stock market right here in the USA.

Ralph Vince writes:

I think we make a huge mistake when we assume that policy affects long term stock prices. Sure, you might have seen events, like a lot of stocks seeing big ex-dates last year, before big tax theft years — but the long term upward drift is a function of evolution. Like our progress has always been — starts and fits.

Sometimes the fits have lasted 950 years! But it always comes around. I like to get up in the morning, put my shoes on, by a few shares of some random something or other. If it goes against me, buy a little more. When it comes around to satisfy my Pythagorean criterion, out she goes.

As I've gotten older, I like to do it with wasting assets, long options.

It makes it more sporting.

Stefan Jovanovich writes:

I wish that we all could agree that prices only count if you can use the money . Zimbabwe's stock market does not have prices for anyone who wants use the money except in Zimbadwe. The Italian stock market was not quite that bad but close enough to make its "performance" entirely fictional from the point of view of anyone wanting to do what people now take for granted - use their dollars to buy/sell "foreign" stocks, close the trades and then take home their winnings - in dollars. That was not possible in Italy after 1922 or in Germany after 1932, for that matter.

As for Mussolini's economic policies, they were far more destructive than the President and Congress' inability to stop writing checks that the Treasury has not collected the money for. In his Battle for the Lira (1926), Mussolini decided that the currency would be fixed at 90 to the pound, even though the price in the foreign exchange market was 55% of that figure. The result was to create an instant bankruptcy for all exporters and those few remaining financial institutions that dealt in international trade. As a result Italy got a head start on the rest of the world; its Depression began in the fall of 1926. But Quota 90 did create a windfall for the Italian industrialists who were Mussolini's supporters; their costs on their imported raw materials were immediately halved. Like the German industrialists after Hitler took power, they saw their order books boom with all the government spending for guns and butter. And look how well that all turned out.

Baldi writes:

Ralph, you write: "As I've gotten older, I like to do it with wasting assets, long options."

Older? You wrote about doing just that in 1992:

"Finally, you must consider this next axiom. If you play a game with unlimited liability, you will go broke with a probability that approaches certainty as the length of the game approaches infinity. Not a very pleasant prospect. The situation can be better understood by saying that if you can only die by being struck by lightning, eventually you will die by being struck by lightning. Simple. If you trade a vehicle with unlimited liability (such as futures), you will eventually experience a loss of such magnitude as to lose everything you have. […]

"There are three possible courses of action you can take. One is to trade only vehicles where the liability is limited (such as long options.) The second is not to trade for an infinitely long period of time. Most traders will die before they see the cataclysmic loss manifest itself (or before they get hit by lightning.) The probability of an enormous winning trade exists, too, and one of the nice things about winning in trading is that you don't have to have the gigantic winning trade. Many smaller wins will suffice. Therefore, if you aren't going to trade in limited liability vehicles and you aren't going to die, make up your mind that you are going to quit trading unlimited liability vehicles altogether if and when your account equity reaches some pre-specified goal. If and when you achieve that goal, get out and don't' ever come back."

Jan

28

The Seminary Bookstore, from Victor Niederhoffer

January 28, 2013 | 5 Comments

One of the pleasures of visiting the declining city of Chicago (perhaps the next Detroit), is to visit the Seminary Bookstore in their new location, 5727 S. University Avenue, They have a great collection of quasi academic books, i.e. the kind that professors write for popular consumption, and the current text books can be bought a few blocks west at the University Bookstore.

One of the pleasures of visiting the declining city of Chicago (perhaps the next Detroit), is to visit the Seminary Bookstore in their new location, 5727 S. University Avenue, They have a great collection of quasi academic books, i.e. the kind that professors write for popular consumption, and the current text books can be bought a few blocks west at the University Bookstore.

Compared to the old store, it has much more room, much more light and glass windows, and plenty of places to sit and read. And unlike the old store, it's possible to find your way out without being buried by a ton of musty books if you don't get lost in the basement. I am one of those unfortunates who was not educated enough in my college days to have a good grounding in all the disciplines that make up the world of knowledge so I like to update myself periodically in areas that I am weak in or should know much more about, especially for market actualization or knowledge to share with my kids.

Perhaps the list of books I bought might be of interest to some scholars or would be market people. Microeconomics by Besanko and Braeutigan

Industrial Organization by Luis Cabral

Investments Bodie, Kane, Marcus (ninth edition)

Stochastic Modeling Barry Nelson

Scorecasting Moskowitz and Wertheim

The Evolution of Plants Wills and McElwain

Survival by Minelli and Mannuci

Thieves, Deceivers and Killers, Agosta

The Birth of the Modern World 1780-1914

The Lions of Tsavo, Patterson

Modeling Binary Data by David Collett (second edition)

Historical Perspectives on the American Economy, Whaples

Viruses, Plagues, and History, Olstone

Plastic (a toxic love story), Feinkel (for the collab for her new business)

The Power of Plagues, Sherman

Quantitative Ecological Theory, Rose

Think Python, O'Reilly (for my kids who want a job in the future).

Beautiful Evidence by Edward Tufte

All of Nonparametric Statistics by Larry Wasserman

Number Shape and Symmetry by Diane Hermann and Paul Sally

Nonparametri Statistics with Applications to Science and Engineering, Paul Kvam and Brani Vidakovic

Discrete Multivariate Analysis by Yvonne Bishop et al